(Press-News.org) PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- Maybe distraction is not always the enemy of learning. It turns out in surprising Brown University psychology research that inconsistent distraction is the real problem. As long as our attention is as divided when we have to recall a motor skill as it was when we learned it, we'll do just fine, according to the new study.

Most learned motor tasks -- driving, playing sports or music, even walking again after injury -- occur with other things going on. Given the messiness of our existence, said lead researcher Joo-Hyun Song, assistant professor of cognitive, linguistic, and psychological sciences, the brain may be able to integrate the division of attention during learning as a cue that allows for better recall when a similar cue is present.

"The underlying assumption people have is that divided attention is bad -- if you divide your attention, your performance should get worse," Song said. "But learning has a later, skill-retrieval part. People haven't studied what's the role of divided attention in memory recall later."

Consistent distraction

Now Song and neuroscientist Patrick Bédard have. Their study, published in the journal Psychological Sciences, involved two main experiments.

In the first, 48 volunteers manipulated a stylus on a touchpad to virtually reach for targets on a computer screen. The trick to learn was that the computer would bend the virtual world by 45 degrees, so the subjects had to compensate. Meanwhile some volunteers also had to perform another task, which was to count symbols that moved by on the screen as they made their awkward reaches. Other volunteers saw the symbols but were told they could ignore them.

Later the subjects would demonstrate their new reaching skills, some with and some without again having to count symbols.

The subjects were therefore split into five groups based on whether they had to endure the symbol distraction either during learning or during recall and to what degree (high or low). For example, the "none-none" group never dealt with the symbols, the "high-none" group were distracted when learning but not during recall and the "high-high" group had their attention equally divided at both times.

When the researchers looked at how well the subjects in each group recalled the task, they found that the high-high group did as well as the none-none group, while the high-none, low-none and none-high groups all struggled. It was as if those who were denied the same degree of distraction during testing as they experienced during learning suffered a disadvantage.

A second surprise

A second experiment showed that the distraction at recall didn't have to be the same kind as the distraction during learning. Song and Bédard put another 50 subjects through a similar set of experiments, but this time the distraction during recall for some volunteers was shapes, for others it was shapes of differing brightness, and for still others it was sounds.

In the end it didn't seem to matter what the distraction was during recall as long as subjects had had a distraction during learning. Everybody who had been distracted in both learning and recall performed better than those who were distracted while learning but undistracted during recall.

Notably, the effect Song measured didn't depend on keeping the external context, for instance the ambient surroundings, consistent. There just had to be the same degree of distraction at both times. In this regard, the study is not merely recapitulating the well-accepted observation that people can remember better when they are in the same context as before. If anything, she said, it suggests that divided attention is more powerful than external context in prompting the kind of recall measured.

Can learning improve?

Song is continuing to study the affects of attention on learning. In her lab she's varying the timing of the distraction, for example.

Another task is to figure out what might be going on in the brain to allow divided attention to be a boost for recall, rather than a hindrance for learning.

"For now my working hypothesis is that this creates an internal representation in which divided attention is associated with the motor learning process, so it can work as an internal cue," Song said.

Song said she is curious about whether understanding the effect could improve rehabilitation. It may be better, for instance, to help patients learn to walk not only in the clinic, but amid the degree of distraction they would encounter on their neighborhood sidewalk.

"Without consideration of attentional contexts in real-life situations, the success of learning and rehabilitation programs may be undermined," she said.

INFORMATION:

The National Institute of General Medical Sciences funded the study (grant: NIH IDeA P20GM103645).

This news release is available in German.

Not all boreholes are the same. Scientists of the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) used mobile measurement equipment to analyze gaseous compounds emitted by the extraction of oil and natural gas in the USA. For the first time, organic pollutants emitted during a fracking process were measured at a high temporal resolution. The highest values measured exceeded typical mean values in urban air by a factor of one thousand, as was reported in ACP journal.

(DOI 10.5194/acp-14-10977-2014)

Emission of trace gases by ...

TORONTO - Dec. 9, 2014 (Toronto) - Scientists at the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (CAMH) have identified a novel drug target that could lead to the development of better antipsychotic medications.

Dr. Fang Liu, Senior Scientist in CAMH's Campbell Family Mental Health Research Institute and Professor in the Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, and her team published their results online in the journal Neuron.

Current treatment for patients with schizophrenia involves taking medications that block or interfere with the action of the neurotransmitter ...

Hummingbirds rely on their ability to hover in order to feed off the nectar of flowers.

It's an incredible feat of flying requiring mind boggling visual processing power, but two University of British Columbia researchers found a glitch in the system, something the tiny birds are powerless to control.

The researchers put hovering hummingbirds through a virtual reality experiment that showed the birds can't control their inflight response to some visual stimuli.

In a laboratory flight arena, hummingbirds hovered around a plastic feeder while images were projected on ...

As solar panels become less expensive and capable of generating more power, solar energy is becoming a more commercially viable alternative source of electricity. However, the photovoltaic cells now used to turn sunlight into electricity can only absorb and use a small fraction of that light, and that means a significant amount of solar energy goes untapped.

A new technology created by researchers from Caltech, and described in a paper published online in the October 30 issue of Science Express, represents a first step toward harnessing that lost energy.

Sunlight is ...

An international team of scientists has discovered the earliest known engravings from human ancestors on a 400,000 year-old fossilised shell from Java.

The discovery is the earliest known example of ancient humans deliberately creating pattern.

"It rewrites human history," said Dr Stephen Munro from School of Archaeology and Anthropology at The Australian National University (ANU).

"This is the first time we have found evidence for Homo erectus behaving this way," he said.

The newly discovered engravings resemble the previously oldest-known engravings, which are ...

Animals that regulate their body temperature through the external environment may be resilient to some climate change but not keep pace with rapid change leading to potentially disastrous outcomes for biodiversity.

A study by the University of Sydney and University of Queensland showed many animals can modify the function of their cells and organs to compensate for changes in the climate and have done so in the past, but the researchers warn that the current rate of climate change will outpace animals' capacity for compensation (or acclimation).

The research has just ...

SAN ANTONIO -- Use of anthracycline-based chemotherapy, a common treatment for breast cancer, has negligible cardiac toxicity in women whose tumors have BRCA1/2 mutations -- despite preclinical evidence that such treatment can damage the heart.

The findings, to be presented at the 2014 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium (SABCS), represent a unique effort between cardiologists and oncologists at Georgetown Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center and MedStar Heart & Vascular Institute in Washington to answer a vital clinical question.

"Our study was prompted by evidence from ...

SALT LAKE CITY, Utah, Dec. 9, 2014 - Myriad Genetics, Inc. (NASDAQ: MYGN) today announced results from a new study that demonstrated the ability of the myRisk™ Hereditary Cancer test to detect 105 percent more mutations in cancer causing genes than conventional BRCA testing alone. The Company also presented two key studies in triple negative breast cancer (TNBC) that show the myChoice™ HRD test accurately predicted response to platinum-based therapy in patients with early-stage TNBC and that the BRACAnalysis® molecular diagnostic test significantly predicted ...

BLOOMINGTON, Ind. -- It's widely known that the Earth's average temperature has been rising. But research by an Indiana University geographer and colleagues finds that spatial patterns of extreme temperature anomalies -- readings well above or below the mean -- are warming even faster than the overall average.

And trends in extreme heat and cold are important, said Scott M. Robeson, professor of geography in the College of Arts and Sciences at IU Bloomington. They have an outsized impact on water supplies, agricultural productivity and other factors related to human health ...

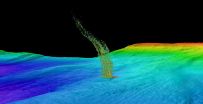

Off the West Coast of the United States, methane gas is trapped in frozen layers below the seafloor. New research from the University of Washington shows that water at intermediate depths is warming enough to cause these carbon deposits to melt, releasing methane into the sediments and surrounding water.

Researchers found that water off the coast of Washington is gradually warming at a depth of 500 meters, about a third of a mile down. That is the same depth where methane transforms from a solid to a gas. The research suggests that ocean warming could be triggering the ...