(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- By figuring out how to precisely order the molecules that make up what scientists call organic glass -- the materials at the heart of some electronic displays, light-emitting diodes and solar cells -- a team of chemists from the University of Wisconsin-Madison has set the stage for more efficient and sturdier portable electronic devices and possibly a new generation of solar cells based on organic materials.

Writing this week (March 23, 2015) in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a team led by UW-Madison chemistry Professor Mark Ediger describes a method capable of routinely imposing order on organic glasses by enabling their production so that the molecules that make up the glasses are ideally positioned.

"Glasses are usually isotropic, meaning their properties are the same from any direction," explains Ediger, a world expert on glass, who conducted the study with UW-Madison researchers Shakeel Dalal and Diane Walters.

Glass, says Ediger, can be made from any number of materials. The most familiar, of course, is window glass, made primarily of the mineral silica. But other types of glass can be made of metal and other materials, and nature makes its own variants such as the volcanic glass obsidian. Organic glasses are made using materials based on carbon instead of silica.

The new organic glasses devised by Ediger's team "have the molecules oriented in specific ways, standing up or lying down," he explains. The orientation affects performance and can confer greater levels of efficiency and durability in the devices they are used in.

While there is precedent for making organic glasses like those described in the new PNAS report, Ediger's team, working with Juan de Pablo and Ivan Lyubimov of the University of Chicago's Institute for Molecular Engineering, delved deep into the process and discovered the key for controlling molecular orientation during manufacture. The process can be exploited to easily and routinely make organic glasses whose molecules are better regimented, conferring enhanced properties of interest.

The discovery is important because organic glasses are widely used in what are called organic light-emitting diodes, the active elements of the displays used in some portable consumer electronics such as cellphones. Perhaps more significantly, the finding by Ediger's team could help advance improved photovoltaic devices, such as solar cells, which convert light to electricity.

"We're thinking about the next generation of photovoltaics," says Ediger, noting that the use of organic glasses in things like solar cells has so far been limited. "That technology is commercially immature and improved control over material properties could have a big impact."

Organic solar cells may prove less expensive to produce than the crystalline silicone photovoltaics commonly used now, he says.

In portable electronics, the work could help underpin new ways to build more durable screens. As many as 150 million such displays are manufactured for cellphones alone each year and the new discovery could result in displays that produce more light using as much as 30 percent less energy.

The key identified by Ediger and his colleagues lies in a process called physical vapor deposition, which is how the organic light-emitting diodes that make up portable electronic displays are mass produced. The process for making the diodes occurs in a vacuum chamber where molecules are heated and evaporated, and then condense in ultrathin layers on a substrate to form the light-emitting display of a cellphone or other device.

"What is new in our work is that we have systematically explored the important control variable, the substrate temperature, and discovered a general pattern for molecular orientation that can be exploited," says Ediger. "Furthermore, we now understand what controls the orientation trapped in particular glasses."

The upshot, he says, could be organic light-emitting diodes substantially more energy efficient than those currently in use.

INFORMATION:

The study was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Science Foundation.

--Terry Devitt, 608-262-8282, trdevitt@wisc.edu

Jupiter may have swept through the early solar system like a wrecking ball, destroying a first generation of inner planets before retreating into its current orbit, according to a new study published March 23 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. The findings help explain why our solar system is so different from the hundreds of other planetary systems that astronomers have discovered in recent years.

"Now that we can look at our own solar system in the context of all these other planetary systems, one of the most interesting features is the absence of planets ...

'Attractive' male birds that mate with many females aren't passing on the best genes to their offspring, according to new UCL research which found promiscuity in male birds leads to small, genetic faults in the species' genome.

Although minor, these genetic flaws may limit how well future generations can adapt to changing environments.

The study, published this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences and funded by the European Research Council, shows for the first time the power of sexual selection - where some individuals are better at securing mates ...

Leprosy is a chronic infection of the skin, peripheral nerves, eyes and mucosa of the upper respiratory tract, affecting over a quarter million people worldwide. Its symptoms can be gruesome and devastating, as the bacteria reduce sensitivity in the body, resulting in skin lesions, nerve damage and disabilities. Until recently, leprosy was attributed to a single bacterium, Mycobacterium leprae; we now suspect that its close relative, Mycobacterium lepromatosis, might cause a rare but severe form of leprosy. Scientists at École Polytechnique Fe?de?rale de Lausanne (EPFL) ...

Western U.S. forests killed by the mountain pine beetle epidemic are no more at risk to burn than healthy Western forests, according to new findings by the University of Colorado Boulder that fly in the face of both public perception and policy.

The CU-Boulder study authors looked at the three peak years of Western wildfires since 2002, using maps produced by federal land management agencies. The researchers superimposed maps of areas burned in the West in 2006, 2007 and 2012 on maps of areas identified as infested by mountain pine beetles.

The area of forests burned ...

A molecule that prevents Type 1 diabetes in mice has provoked an immune response in human cells, according to researchers at National Jewish Health and the University of Colorado. The findings, published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, suggest that a mutated insulin fragment could be used to prevent Type 1 diabetes in humans.

"The incidence of Type 1 diabetes is increasing dramatically," said John Kappler, PhD, professor of Biomedical Research at National Jewish Health. "Our findings provide an important proof of concept in humans for a ...

Non-native plants are commonly listed as invasive species, presuming that they cause harm to the environment at both global and regional scales. New research by scientists at the University of York has shown that non-native plants - commonly described as having negative ecological or human impacts - are not a threat to floral diversity in Britain.

Using repeat census field survey data for British plants from 1990 and 2007, Professor Chris Thomas and Dr Georgina Palmer from the Department of Biology at York analysed changes in the cover and diversity of native and non-native ...

A 60-year-old maths problem first put forward by Nobel laureate Enrico Fermi has been solved by researchers at the University of East Anglia, the Università degli Studi di Torino (Italy) and the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (US).

In 1955, a team of physicists, computer scientists and mathematicians led by Fermi used a computer for the first time to try and solve a numerical experiment.

The outcome of the experiment wasn't what they were expecting, and the complexity of the problem underpinned the then new field of non-linear physics and paved the way for six ...

Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University who develop snake-like robots have picked up a few tricks from real sidewinder rattlesnakes on how to make rapid and even sharp turns with their undulating, modular device.

Working with colleagues at the Georgia Institute of Technology and Zoo Atlanta, they have analyzed the motions of sidewinders and tested their observations on CMU's snake robots. They showed how the complex motion of a sidewinder can be described in terms of two wave motions - vertical and horizontal body waves - and how changing the phase and amplitude of ...

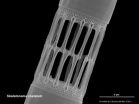

Troy, N.Y. - A team of researchers, including Rensselaer professor Morgan Schaller, has used mathematical modeling to show that continental erosion over the last 40 million years has contributed to the success of diatoms, a group of tiny marine algae that plays a key role in the global carbon cycle. The research was published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Diatoms consume 70 million tons of carbon from the world's oceans daily, producing organic matter, a portion of which sinks and is buried in deep ocean sediments. Diatoms account for over ...

Archaeologists working in Guatemala have unearthed new information about the Maya civilization's transition from a mobile, hunter-gatherer lifestyle to a sedentary way of life.

Led by University of Arizona archaeologists Takeshi Inomata and Daniela Triadan, the team's excavations of the ancient Maya lowlands site of Ceibal suggest that as the society transitioned from a heavy reliance on foraging to farming, mobile communities and settled groups co-existed and may have come together to collaborate on construction projects and participate in public ceremonies.

The findings, ...