(Press-News.org) (SALT LAKE CITY)--Recent research has linked the thin air of higher elevations to increased rates of depression and suicide. But a new study shows there's also good news from up in the aspens and pines: The prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) decreases substantially as altitude increases.

In Utah, for example, an analysis of information from two national health surveys correlated with the average state elevation of 6,100 feet showed that the rate of diagnosed ADHD cases is about 50 percent of states at sea level. In Salt Lake City, whose elevation is about 4,300 feet, diagnosed ADHD prevalence is approximately 38 percent less than at sea level.

One potential reason for the decreased rate of ADHD, University of Utah researchers believe, is higher levels of dopamine produced as a reaction to hypobaric hypoxia--a condition caused when people breathe air with less oxygen at higher elevations. Decreased dopamine levels are associated with ADHD so when levels of the hormone increase with elevation, the risk for getting the disorder diminishes. There are other potential reasons for the disparities in the rates of the disorder, such as regional inconsistencies in diagnosing ADHD.

The study findings, published in the Journal of Attention Disorders online, have important implications for potentially treating ADHD, according to Douglas G. Kondo, M.D., assistant professor of psychiatry and senior author on the study. "Our previous studies of mood disorders and suicide consistently suggest that hypobaric hypoxia associated with altitude may serve as a kind of environmental stressor," Kondo says. "But these results raise the question of whether, in the case of ADHD, altitude may be a protective factor."

Rebekah Huber, a doctoral candidate in educational psychology at the University of Utah, is the first author. Huber works in the research group of Perry F. Renshaw, M.D., Ph.D., M.B.A., a University of Utah professor of psychiatry, USTAR investigator and a co-author on the study.

Huber, Kondo, Renshaw and their colleagues conducted the study with data from two national health surveys and information on average state elevations taken from NASA's Shuttle Radar Topography Mission and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency.

The National Survey on Children's Health contacted 91,642 households in 2007 and found that 73,123 children ages 4-17 had been diagnosed with mild, moderate or severe ADHD by a physician or other health care provider. The 2010 National Survey of Children with Special Healthcare Needs contacted 372,689 households and found that 40,242 children in that age range had been diagnosed with full ADHD.

The researchers correlated the number of cases of diagnosed ADHD with average elevations in the lower 48 states and the District of Columbia as reported by the federal agencies to determine rates of ADHD. From this, they derived data on ADHD rates at sea level and above and found that for every 1-foot increase in elevation, the likelihood of being diagnosed with ADHD by a healthcare provider decreases by .001 percent.

The data showed that North Carolina, whose average elevation is 869 feet above sea level, had the highest percentage of children diagnosed with ADHD - 15.6 percent. Delaware, Louisiana and Alabama--all states with an average elevation of less than 1,000 feet--followed closely behind North Carolina with high percentages of ADHD.

Nevada--with an average elevation of 5,517 feet above sea level--had the lowest percentage at 5.6. Utah had one of the lowest rates of ADHD, 6.7 percent. All of the Mountain West states rated well below average for the percentage of children diagnosed with ADHD. The study also took into account other factors--such as birth weight, ethnicity, and sex (males are more likely to have ADHD)-- that could affect ADHD diagnoses and influence the rate of the disorder in each state.

This study follows research in which Renshaw and colleagues at the University of Utah and in South Korea showed correlations between increased rates of suicide and depression with higher altitudes.

The decrease in ADHD at elevation doesn't mean people need to start moving to the mountains, according to Renshaw. But the research results do have potential implications for treating the disorder.

"To treat ADHD we very often give someone medication that increases dopamine," he says. "Does this mean we should be increasing medications that target dopamine? Parents or patients might want to take this information to their health care providers to discuss it with them."

INFORMATION:

DURHAM, N.C. - An estimated 9 percent of adults in the U.S. have a history of impulsive, angry behavior and have access to guns, according to a study published this month in Behavioral Sciences and the Law. The study also found that an estimated 1.5 percent of adults report impulsive anger and carry firearms outside their homes.

Angry people with ready access to guns are typically young or middle-aged men, who at times lose their temper, smash and break things, or get into physical fights, according to the study co-authored by scientists at Duke, Harvard, and Columbia ...

Amsterdam, The Netherlands, April 8, 2015 -- Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common cause of chronic liver disease in the western world. A new study published in the Journal of Hepatology shows that exercise, regardless of frequency or intensity, benefits obese and overweight adults with NAFLD.

NAFLD is considered the hepatic manifestation of metabolic syndrome and is commonly associated with obesity and diabetes. There are no approved drug treatments for NAFLD, but lifestyle interventions such as diet, exercise, and the resulting weight loss have ...

A July, 2014 Call to Action to Prevent Skin Cancer by acting Surgeon General Dr. Boris Lushniak points out that indoor tanning is "strongly associated with increased skin cancer risk," but stops short of reporting that tanning causes cancer. A University of Colorado Cancer Center opinion published today in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine points out that UV tanning meets the same criteria as smoking as a cause of cancer and argues that announcing the causality could save lives.

"In 1964 when the Surgeon General finally reported that smoking causes lung cancer, ...

The secret communication of gibbons has been interpreted for the first time in a study published in the open access journal BMC Evolutionary Biology. The research reveals the likely meaning of a number of distinct gibbon whispers, or 'hoo' calls, responding to particular events and types of predator, and could provide clues on the evolution of human speech.

While lar gibbons (Hylobates lar) are mainly known for their loud and conspicuous songs, they can also produce a number of soft call types known as 'hoo's. These subtle calls have been alluded to in studies dating ...

Life has adapted to all sorts of extreme environments on Earth, among them, animals like the deer mouse, shimmying and shivering about, and having to squeeze enough energy from the cold, thin air to fuel their bodies and survive.

Now, in a new publication in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution, Scott, Cheviron et al., have examined the underlying muscle physiology from a group of highland and lowland deer mice. Deer mice were chosen because they exhibit the most extreme altitude range of any North American mammal, occurring below sea levels in Death Valley to ...

Cold Spring Harbor, NY - The prefrontal cortex (PFC) plays an important role in cognitive functions such as attention, memory and decision-making. Faulty wiring between PFC and other brain areas is thought to give rise to a variety of cognitive disorders. Disruptions to one particular brain circuit--between the PFC and another part of the brain called the thalamus--have been associated with schizophrenia, but the mechanistic details are unknown. Now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory scientists have discovered an inhibitory connection between these brain areas in mice that ...

The Burgess Shale Formation, in the Canadian Rockies of British Columbia, is one of the most famous fossil locations in the world. A recent Palaeontology study introduces a 508 million year old (middle Cambrian) arthropod--called Yawunik kootenayi--from exceptionally preserved specimens of the new Marble Canyon locality within the Burgess Shale Formation.

Its frontal appendage--the "megacheiran great appendage"--is remarkably adorned with teeth, emphasizing an advanced predatory function. The appendage also had long hair-like flagella at the end that likely served a sensory ...

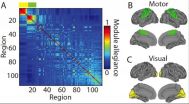

Why do some people learn a new skill right away, while others only gradually improve? Whatever else may be different about their lives, something must be happening in their brains that captures this variation.

Researchers at the University of Pennsylvania, the University of California, Santa Barbara, and Johns Hopkins University have taken a network science approach to this question. In a new study, they measured the connections between different brain regions as participants learned to play a simple game. The differences in neural activity between the quickest and slowest ...

The results appear in the 2015 2nd issue of the journal of Human Genome Variation. To see a video about the partnership between Champions and Insilico, visit: http://tinyurl.com/InsilicoChampions .

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States. More than 50,000 people die of CRC each year due to tumor spreading to other organs and almost half of all newly diagnosed patients are in an advanced stage of cancer (metastatic CRC or mCRC) when they are first diagnosed.

With the development ...

A Northwestern University research team potentially has found a safer way to keep blood vessels healthy during and after surgery.

During open-heart procedures, physicians administer large doses of a blood-thinning drug called heparin to prevent clot formation. When given too much heparin, patients can develop complications from excessive bleeding. A common antidote is the compound protamine sulfate, which binds to heparin to reverse its effects.

"Protamine is a natural compound that has been used in surgeries for many decades," said Guillermo Ameer, professor of biomedical ...