(Press-News.org) Researchers at Case Western Reserve University School of Dental Medicine have unraveled one of the mysteries of how a small group of immune cells work: That some inflammation-fighting immune cells may actually convert into cells that trigger disease.

Their findings, recently reported in the journal Pathogens, could lead to advances in fighting diseases, said the project's lead researcher Pushpa Pandiyan, an assistant professor at the dental school.

The cells at work

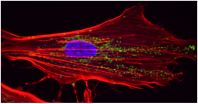

A type of white blood cell, called T-cells, is one of the body's critical disease fighters. Regulatory immune cells, called "Tregs," direct T-cells and control unwanted immune reactions that cause inflammation. They are known to produce only anti-inflammatory proteins to keep inflammation caused by disease in check.

But using mouse models, the researchers studied how the body fights off a common oral fungus that causes thrush. They found that these harmful invaders activate a mechanism in Tregs that could transform the inflammation-fighting cells into cells that allow the disease to flourish.

The study

When the immune system functions normally, disease-fighting T-cells produce inflammatory secretions -- proteins that can cause symptoms, such as soreness or swelling at the infected site. This process is evident, for example, when a cut or glands swell from the infection's inflammatory reaction.

Once the invader is gone, the disease-fighting cells -- with help from Treg cells -- normally shut down those proteins to control long-term inflammation.

But the researchers found that, during oral thrush, yeast sugars on the surface of the disease-causing fungus act as a binding agent and can activate a small population of Treg cells to make inflammatory proteins themselves. (The researchers are calling this novel subset of malfunctioning cells Treg-17 cells).

"An excess of these malfunctioning cells can lead to the inflammatory disease process instead of stopping it," she said.

Other binding agents normally found in the body may create these cells and contribute to continued inflammation, the researchers concluded.

Other researchers have reported the presence of these cells in many human inflammation conditions, such as psoriasis, periodontitis and arthritis. Until now, however, the mechanisms of how these cells developed were not completely understood, Pandiyan said.

The implications

The findings will help researchers understand the origin of cells they suspect may keep the disease active or, at a minimum, don't battle inflammation. Pandiyan believes the knowledge could lead to new ways to fight diseases, such as:

Using the converting Tregs (Treg-17) to identify chronic inflammation, including oral inflammation.

Using the persistence of Treg-17 cells to indicate an excessive amount of the inflammatory proteins.

Using the presence of the binding agent that triggers the cell's conversion as a point to use medicines to block its connection to Tregs.

Future studies will investigate whether these cells are actually perpetrating inflammation.

INFORMATION:

The study, "TLR-2 Signaling Promotes IL-17A Production in CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ Regulatory Cells during Oropharyngeal Candidiasis," was recently reported in Pathogens.

CWRU Department of Biological Science researchers Natarajan Bhaskaran, Samuel Cohen, Aaron Weinberg and Yifan Zhang contributed to the study.

Scientists from the Institut Pasteur and CNRS, in collaboration with scientists from the Institut Gustave Roussy and CEA, have succeeded in restoring normal activity in cells isolated from patients with the premature aging disease Cockayne syndrome. They have uncovered the role played in these cells by an enzyme, the HTRA3 protease.

This enzyme is overexpressed in Cockayne syndrome patient cells, and leads to mitochondrial defects, which in turn play a crucial role in the appearance of symptoms leading to aging in affected children. These findings, published in the ...

BOZEMAN, Mont. -- Montana State University researchers and their collaborators have published their findings about a chemical compound that shows potential for treating rheumatoid arthritis.

The paper ran in the June issue of the Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (JPET), and one of its illustrations is featured on the cover. JPET is a leading scientific journal that covers all aspects of pharmacology, a field that investigates the effects of drugs on biological systems and vice versa.

"This journal is one of the top journals that reports new types ...

According to small and medium-sized enterprises, sizable social security and other wage-related costs still form the single greatest obstacle for improving productivity. Additionally, a lack of competence among supervisors was also seen as an obstacle for productivity. This information is from a newly published survey by the Lappeenranta University of Technology (LUT), which is a follow-up to a study on the obstacles that restrain the productivity of companies published in 1997. A total of 239 representatives from Finnish small and medium-sized enterprises responded to ...

PHOENIX -- Prior studies have shown that most dog bite injuries result from family dogs. A new study conducted by Mayo Clinic and Phoenix Children's Hospital shed some further light on the nature of these injuries.

The American Veterinary association has designated this week as Dog Bite Prevention Week.

The study, published last month in the Journal of Pediatric Surgery, demonstrated that more than 50 percent of the dog bites injuries treated at Phoenix Children's Hospital came from dogs belonging to an immediate family member.

The retrospective study looked at a ...

The advice, whether from Shakespeare or a modern self-help guru, is common: Be true to yourself. New research suggests that this drive for authenticity -- living in accordance with our sense of self, emotions, and values -- may be so fundamental that we actually feel immoral and impure when we violate our true sense of self. This sense of impurity, in turn, may lead us to engage in cleansing or charitable behaviors as a way of clearing our conscience.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"Our work ...

Two words that arouse immediate fear in some people inspire something else altogether in Jennifer Fill.

"I love snakes and fire," Fill says. "When I was looking at grad schools, I thought, 'if I can just combine those two things, I bet I'll be really happy.'"

It's not about cozy campfires or garden-variety garters for Fill, a biologist who recently defended her dissertation at the University of South Carolina. The fires she's interested in are forest fires, and the snake that was the subject of her doctoral studies is Crotalus adamanteus, commonly called the eastern diamondback ...

A new report on New York City's Expanded Success Initiative (ESI), which is designed to boost college and career readiness among Black and Latino male students, finds that the schools involved are changing the way they operate and offering students opportunities they would not otherwise have.

"There is strong evidence that these schools are doing something different as a result of ESI," says the study's lead author, Adriana Villavicencio, senior research associate at the Research Alliance for New York City Schools. "We are seeing important shifts in the tone and culture ...

Bacteria that live in the guts of cicadas have split into many separate but interdependent species in a strange evolutionary phenomenon that leaves them reliant on a bloated genome, a new paper by CIFAR Fellow John McCutcheon's lab (University of Montana) has found.

Cicadas subsist on tree sap, which doesn't provide them all the nutrients they need to live. Bacteria in their gut, including one called Hodgkinia, turns the sap into amino acids that sustain them during their unusual lives. Cicadas spend most of their lives underground before emerging in droves, singing loudly, ...

The sight of skilful aerial manoeuvring by flocks of Greylag geese to avoid collisions with York's Millennium Bridge intrigued mathematical biologist Dr Jamie Wood. It raised the question of how birds collectively negotiate man-made obstacles such as wind turbines which lie in their flight paths.

It led to a research project with colleagues in the Departments of Biology and Mathematics at York and scientists at the Animal and Plant Health Agency. The study found that the social structure of groups of migratory birds may have a significant effect on their vulnerability ...

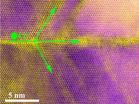

Most people see defects as flaws. A few Michigan Technological University researchers, however, see them as opportunities. Twin boundaries -- which are small, symmetrical defects in materials -- may present an opportunity to improve lithium-ion batteries. The twin boundary defects act as energy highways and could help get better performance out of the batteries.

This finding, published in Nano Letters earlier this year, turns a previously held notion of material defects on its head. Reza Shahbazian-Yassar helped lead the study and holds a joint appointment at Michigan ...