(Press-News.org) To predict how a seasonal influenza epidemic will spread across the United States, one should focus more on the mobility of people than on their geographic proximity, a new study suggests.

PLOS Pathogens published the analysis of transportation data and flu cases conducted by Emory University biologists. Their results mark the first time genetic patterns for the spread of flu have been detected at the scale of the continental United States.

"We found that the spread of a flu epidemic is somewhat predictable by looking at transportation data, especially ground commuter networks and H1N1," says Brooke Bozick, who led the study as a graduate student in Emory's Population Biology, Ecology and Evolution program. "Finding these kinds of patterns is the first step in being able to develop targeted surveillance and control strategies."

The co-author of the study is Leslie Real, Emory professor of biology and Bozick's PhD adviser.

One of the fundamental ideas in ecology is isolation by distance: The further apart things are geographically, the more distant they tend to be genetically. This idea applies to disease ecology in the cases of animals that do not travel far from where they are born. Rabies spread by raccoons, for instance, tends to generate a wave-like pattern of transmission across a geographic space.

People, however, are much more mobile, often traveling by rail, road and air.

The human mobility effect of an epidemic stands out starkly on the global scale. For instance, during the 2003 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), airline travel clearly connected cases in people from Asia and Canada.

The researchers wanted to see if they could detect a correlation to mobility and the genetic structure of seasonal flu cases on a national scale for the United States.

The study tapped Genbank, an online, public repository of genetic flu data, to analyze U.S. cases from 2003 to 2013 for two different subtypes of seasonal flu: H3N2 and H1N1. Transportation data for that decade was drawn from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, to map out networks of air travel and ground commutes, and the number of people moving along them during the flu season.

The researchers compared genetic distance of the flu subtypes with their geographic distance and the measures of distance defined by airline and commuter transportation networks.

They found some correlations in both subtypes for all the distance metrics used. The correlations were seen a greater proportion of the time, however, when looking at commuter movements and the H1N1 subtype.

"H1N1 tends to be a milder subtype of flu that spreads slower, so that may make it easier to pick up the pattern across shorter-distance commutes," Bozick says. "We think that a similar pattern for H3N2 may exist. The pattern may just be harder to detect, since H3N2 tends to be more virulent and spread faster, from coast-to-coast."

The study shows that there are underlying spatial patterns in the genetic data, and that they are dependent on how the "distance" between locations is being measured, she adds.

"Humans can move long distances very rapidly so the idea that geographic proximity is key to determining disease spread doesn't always hold," Bozick says. "The patterns we found are likely influenced by states with many commuters, and the identification of these states, as well as network pathways that contribute substantially to influenza spread, is an important next step for epidemiological research."

INFORMATION:

Baboons live in a strongly hierarchical society, but the big guys don't make all the decisions.

A new study from the University of California, Davis, reveals -- through GPS tracking -- that animals living in complex, stratified societies make some decisions democratically. The study breaks ground in how animal behavior data is collected.

The study is being published Friday (June 19) in Science.

"It's not necessarily the biggest alpha males that influence where groups go," said co-author Meg Crofoot, assistant professor of anthropology at UC Davis. "Our results illustrate ...

DNA from the 8,500-year-old skeleton of an adult man found in 1996, in Washington, is more closely related to Native American populations than to any other population in the world, according to an international collaborative study conducted by scientists at the University of Copenhagen and the Stanford University School of Medicine.

The finding challenges a 2014 study that concluded, based on anatomical data, that Kennewick Man was more related to indigenous Japanese or Polynesian peoples than to Native Americans. The study is likely to reignite a long-standing legal ...

NASA provided four different views of Tropical Depression Bill as it continued traveling through the south-central U.S. and into the Ohio Valley. NASA's Aqua and Terra satellite provided infrared and visible imagery while NASA/NOAA's GOES Project animated NOAA's GOES-East satellite imagery to show the storm's progression since landfall. The Global Precipitation Measurement or GPM core satellite also showed rainfall estimates and locations.

On June 18, the National Weather Service, Weather Prediction Center (NWS/WPC) noted that flood and flash flood watches and warnings ...

Kangaroos prefer to use one of their hands over the other for everyday tasks in much the same way that humans do, with one notable difference: generally speaking, kangaroos are lefties. The finding, reported in the Cell Press journal Current Biology on June 18--the first to consider handedness in wild kangaroos--challenges the notion that "true" handedness among mammals is a feature unique to primates.

"According to a special-assessment scale of handedness adopted for primates, kangaroos pulled down the highest grades," says Yegor Malashichev of Saint Petersburg State ...

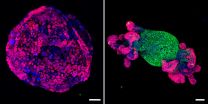

Anti-cancer strategies generally involve killing off tumor cells. However, cancer cells may instead be coaxed to turn back into normal tissue simply by reactivating a single gene, according to a study published June 18th in the journal Cell. Researchers found that restoring normal levels of a human colorectal cancer gene in mice stopped tumor growth and re-established normal intestinal function within only 4 days. Remarkably, tumors were eliminated within 2 weeks, and signs of cancer were prevented months later. The findings provide proof of principle that restoring the ...

American scientists have discovered that a drug commonly used to treat osteoporosis in humans also stimulates the production of cells that control insulin balance in diabetic mice. While other compounds have been shown to have this effect, the drug (Denosumab) is already FDA approved and could more quickly move to clinical trials as a diabetes treatment. The research is published June 18 in Cell Metabolism.

Diabetes is a major health issue worldwide that arises due to a deficiency of insulin-producing beta cells in the pancreas. In type 1 diabetes, beta cells die from ...

Cutaneous melanoma, the most deadly form of skin cancer, is now believed to be divided into four distinct genomic subtypes, say researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, a finding that could prove valuable in the ever-increasing pursuit of personalized medicine.

As part of The Cancer Genome Atlas, researchers identified four melanoma subtypes: BRAF, RAS, NF1 and Triple-WT, which were defined by presence or absence of mutations from analysis of samples obtained from 331 patients. The five-year study resulted from an international collaboration of ...

PHILADELPHIA -- Most of us need seven to eight hours of sleep a night to function well, but some people seem to need a lot less sleep. The difference is largely due to genetic variability. In research published online June 18th in Current Biology, researchers report that two genes, originally known for their regulation of cell division, are required for normal slumber in fly models of sleep: taranis and Cyclin-dependent kinase 1 (Cdk1).

'There's a lot we don't understand about sleep, especially when it comes to the protein machinery that initiates the process on the ...

In 2012, researchers at the Stanford University School of Medicine showed that heart muscle cells made from the skin of people with a cardiac condition called dilated cardiomyopathy beat with less force than those made from the skin of healthy people. These cells also responded less readily to the waves of calcium that control the timing and strength of each contraction.

Now, the same research team has teased apart the molecular basis for these differences and identified a drug treatment that at least partially restores function to diseased cells grown in a laboratory ...

Adult neural stem cells, which are commonly thought of as having the ability to develop into many type of brain cells, are in reality pre-programmed before birth to make very specific types of neurons, at least in mice, according to a study led by UC San Francisco researchers.

"This work fundamentally changes the way we think about stem cells," said principal investigator Arturo Alvarez-Buylla, UCSF professor of neurological surgery, Heather and Melanie Muss Endowed Chair and a principal investigator in the UCSF Brain Tumor Research Center and the Eli and Edythe Broad ...