(Press-News.org) This news release is available in German.

Acute liver failure is a rare yet life-threatening disease for young children. It often occurs extremely rapidly, for example, when a child has a fever. Yet in around 50 percent of cases it is unclear as to why this happens. Now, a team of researchers working on an international research project headed by Technische Universität München (TUM), the Helmholtz Zentrum Munich and Heidelberg University Hospital have discovered a link between the disease and mutations in a specific gene. The researchers used whole genome sequencing to uncover the mutations, which affect transport processes in cells.

According to the European Union, a disease such as acute liver failure is classified as rare if it affects less than five in 10,000 people. Yet despite low patient numbers, research into rare diseases has been on the rise in recent years. The reason for this is that many of these illnesses have a genetic cause that researchers can pinpoint. The findings could also provide important insights into metabolic processes in healthy people or serve as a model for other diseases.

Using sequence analyses to identify genetic defects

Professor Georg Hoffmann at the pediatric hospital in Heidelberg has spent 20 years caring for several patients who have suffered from recurrent acute liver failure since childhood. The similarities in the progression of the disease led him to suspect that there might be a common cause. Dr. Tobias Haack and Dr. Holger Prokisch at the Institute for Human Genetics at TUM and the Helmholtz Zentrum Munich have been examining four children suffering from recurrent, fever-dependent liver failure in a bid to identify a genetic cause. "In our study, we initially focused on the genetic similarities in these children to determine a possible cause for their disease," explains Haack.

The researchers used exome sequencing to do this, a process that involves sequencing all subsets of a patient's DNA that contain information on creating protein. They also examined the DNA of close family members. In multiple instances, they discovered mutations in one specific gene. "We identified mutations in the NBAS gene in a total of 11 patients. This is the first time that we have been able to establish a link between this gene and liver disease. This discovery could also be interesting for other illnesses," summarizes Prokisch.

Mutations disrupt transport processes

However, the researchers were keen to find out exactly how these mutations affect cellular processes. To do this, they carried out a number of molecular biology experiments. These revealed that when the mutations were present in the NBAS gene, only small amounts of the NBAS protein were created. NBAS is involved in cell transport processes that pack proteins in vesicles and transport them from one cell compartment to another. "We were able to show that the faulty protein is more susceptible to heat. This means that when an individual has a fever, there are fewer proteins available for coordinating the transport processes. This, in turn, can have a negative impact on metabolic processes in the liver in an acute situation," elaborates Prokisch.

The researchers' primary aim is to improve the diagnosis of rare diseases such as acute liver failure in childhood and pave the way for targeted treatment. Haack believes that the results give them an important starting point: "When a child suffers from liver failure triggered by fever, we can now specifically investigate the NBAS gene."

"Diagnosis already triggers a specific therapeutic path," adds Hoffmann. "Over the years, we have been able to empirically develop a therapy that uses specific drugs as well as sugar and fat infusions. These can be immediately administered once a patient is diagnosed. We can now use the latest findings to further improve our therapeutic approach."

INFORMATION:

Original publication

T. B. Haack, C. Staufner, M. G. Köpke, B. K. Straub, S. Kölker, C. Thiel, P. Freisinger, I. Baric, P. J. McKiernan, N. Dikow, I. Harting, F. Beisse, P. Burgard, U. Kotzaeridou, J. Kühr, U. Himbert, R. W. Taylor, F. Distelmaier, J. Vockley, L. Ghaloul-Gonzalez, J. Zschocke, L. S. Kremer, E. Graf, T. Schwarzmayr, D. M. Bader, J. Gagneur, T. Wieland, C. Terrile, T. M. Strom, T. Meitinger, G. F. Hoffmann und H. Prokisch, Biallelic Mutations in NBAS Cause Recurrent Acute Liver Failure with Onset in Infancy, American Journal of Human Genetics, June 2015.

DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2015.05.009

Contact

Dr. Tobias Haack

Institute for Human Genetics at Technische Universität München and Helmholtz Zentrum Munich

Phone: +49 89 4140 - 9889

Email: tobias.haack@helmholtz-muenchen.de

New research led by the University of Southampton is paving the way to protect the endangered European eel as they migrate through rivers to the ocean.

The European eel, a fish of high cultural, commercial and conservation concern, has suffered a dramatic decline over recent decades, with the number of juvenile fish returning to rivers down by over 90 per cent.

While several explanations (including overfishing, pollution and climate change) have been proposed for the cause of this demise, one of the key factors is river infrastructure, such as hydropower stations, ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

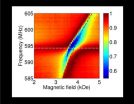

Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) have identified a system that could store quantum information for longer times, which is critical for the future of quantum computing. This study was recently published in Physical Review Letters.

Quantum computing -- which aims to use particles on the atomic scale to make calculations and store the results -- has the potential to solve some key problems much faster than current computers.

To make quantum computing a reality, ...

(NEW YORK CITY - July 1, 2015) A novel synthetic hormone that makes certain skin cells produce more melanin significantly increases pain-free sun exposure in people with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare, genetic disorder resulting in excruciating pain within minutes of sun exposure. Two Phase III trials, conducted in Europe and in the United States by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and six other U.S. sites, showed that the duration of pain-free time in the sun and quality of life were significantly improved by treatment with afamelanotide, ...

Pregnancy and motherhood are both wonderful and worrisome times - could public health campaigns and social stereotypes be contributing to anxiety for mothers? Researchers from Monash University have identified links between perinatal anxiety and social and health messages that women are exposed to during the perinatal period, the period immediately before and after birth.

In a paper recently published in Women's Studies International Forum, Dr Heather Rowe and Professor Jane Fisher from the Jean Hailes Research Unit within the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine ...

Unwanted, intrusive visual memories are a core feature of stress- and trauma-related clinical disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but they can also crop up in everyday life. New research shows that even once intrusive memories have been laid down, playing a visually-demanding computer game after reactivating the memories may reduce their occurrence over time.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"This work is the first to our knowledge to show that a 'simple cognitive blockade' ...

Spider-like cells inside the brain, spinal cord and eye hunt for invaders, capturing and then devouring them. These cells, called microglia, often play a beneficial role by helping to clear trash and protect the central nervous system against infection. But a new study by researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) shows that they also accelerate damage wrought by blinding eye disorders, such as retinitis pigmentosa. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"These findings are important because they suggest that microglia may provide a target for entirely ...

A new method for calculating the exact time of death, even after as much as 10 days, has been developed by a group of researchers at the University of Salzburg.

Currently, there are no reliable ways to determine the time since death after approximately 36 hours. Initial results suggest that this method can be applied in forensics to estimate the time elapsed since death in humans.

By observing how muscle proteins and enzymes degrade in pigs, scientists at the University of Salzburg have developed a new way of estimating time since death that functions up to at least ...

When remembering something from our past, we often vividly re-experience the whole episode in which it occurred. New UCL research funded by the Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust has now revealed how this might happen in the brain.

The study, published in Nature Communications, shows that when someone tries to remember one aspect of an event, such as who they met yesterday, the representation of the entire event can be reactivated in the brain, including incidental information such as where they were and what they did.

"When we recall a previous life event, ...

Classical Brownian motion theory was established over one hundred year ago, describing the stochastic collision behaviors between surrounding molecules. Recently, researchers from Technical Institute of Physics and Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered that the self-powered liquid metal motors in millimeter scale demonstrated similar Brownian like motion behaviors in alkaline solution. And the force comes from the hydrogen gas stream generated at the interface between liquid metal motor and its contacting substrate bottom.

Ever since the irregular motions ...

A group of the world's top doctors and scientists working in cardiology and preventive medicine have issued a call to action to tackle the global problem of deaths from non-communicable diseases (NCDs), such as heart problems, diabetes and cancer, through healthy lifestyle initiatives.

They say that identifying the enormous burden caused by NCDs is not enough and it is time for "all hands on deck" to pursue strategies both within and outside traditional healthcare systems that will succeed in promoting healthier lifestyles in order to prevent or delay health conditions ...