(Press-News.org) Researchers at the Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST) have found a way to stimulate the growth of axons, which may spell the dawn of a new beginning on chronic SCI treatments.

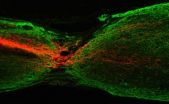

Chronic spinal cord injury (SCI) is a formidable hurdle that prevents a large number of injured axons from crossing the lesion, particularly the corticospinal tract (CST). Patients inflicted with SCI would often suffer a loss of mobility, paralysis, and interferes with activities of daily life dramatically. While physical therapy and rehabilitation would help the patients to cope with the aftermath, axonal regrowth potential of injured neurons was thought to be intractable.

No outside stimulants are needed; the growth driver lies within the neurons themselves.

Inside our DNA, in particular.

In the July 1st issue of The Journal of Neuroscience, HKUST researchers report that the deletion of the PTEN gene would enhance compensatory sprouting of uninjured CST axons. Furthermore, the deletion up-regulated the activity of another gene, the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), which promoted regeneration of CST axons. Axons transmit information to different neurons, muscles, and glands; as bundles they help make up nerves.

Led by Kai Liu, PhD, the study's senior author and assistant professor in life sciences at HKUST, the research team initiated PTEN deletion on mice after pyramidotomy. Similar treatment procedures were carried out on a 2nd group 4 months after severe spinal cord injuries, and a 3rd group after 12 months. The team recorded a regenerative response of CST axons in all 3 samples--showing that PTEN deletion stimulates CST sprouting and regeneration, even though the injury was sustained a long time ago.

"As one of the long descending tracts controlling voluntary movement, the corticospinal tract (CST) plays an important role for functional recovery after spinal cord injury," says Professor Liu. "The regeneration of CST has been a major challenge in the field, especially after chronic injuries. Here we developed a strategy to modulate PTEN/mTOR signaling in adult corticospinal motor neurons in the post-injury paradigm."

"It not only promoted the sprouting of uninjured CST axons, but also enabled the regeneration of injured axons past the lesion in a mouse model of spinal cord injury, even when treatment was delayed up to 1 year after the original injury. The results considerably extend the window of opportunity for regenerating CST axons severed in spinal cord injuries.

Compared with acute injury, axons face more barriers to regenerate after chronic SCI. Previously, scientists have shown that Axon retraction may further increase the distance that axons need to travel; Extracellular matrices, which become well consolidated around the chronic lesion site, also increases inhibition. Neuronal aging may also add obstacles to regrowth. In light of all of these challenges, it is indeed surprising to find that CST axons can still regenerate after 1 year.

"It is interesting to find that chronically injured neurons retain the ability to reform tentative synaptic connections," says Liu. "PTEN inhibition can be targeted on particular neurons, which means that we can apply the procedure specifically on the region of interest as we continue our research."

INFORMATION:

This study was supported in part by the Hong Kong Research Grants Council Theme-Based Research Scheme

(Grant T13-607/12R), the National Key Basic Research Program of China (Grant 2013CB530900), the Research Grants

Council of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (Grants AoE/M-09/12, HKUST5/CRF/12R, AoE/M-05/12,

C4011-14R, 662011, 662012, 689913, and 16101414), and the Hong Kong Spinal Cord Injury Fund.

For a number of years now, scientific literature has questioned whether mortality rates depend on socioeconomic differences among the population. Recently, a new study carried out in 15 European cities - including Barcelona and Madrid - detected inequalities for the majority of causes, concluding that higher levels of poverty are associated with higher mortality rates and there is a great deal of variation among areas.

Social inequality is increasingly considered to be a public health problem. However, scant research has been carried out into associating these differences ...

A team comprised of scientists at VIB, KU Leuven and UZ Leuven has made significant progress in uncovering the connection between psychological factors and the immune system. Their findings are based on an investigation of a massive drinking water contamination incident in Belgium in 2010, and are now published in the leading international medical journal Gut.

In December 2010, the Belgian communities of Schelle and Hemiksem in the province of Antwerp faced an outbreak of gastroenteritis, with more than 18,000 people exposed to contaminated drinking water. During the ...

Scientists have pioneered the use of a high-powered imaging technique to picture in exquisite detail one of the central proteins of life - a cellular recycling unit with a role in many diseases.

The proteasome complex is present in all multicellular organisms, and plays a critical role in cancer by allowing cancer cells to divide rapidly.

Researchers used a technique called electron cryo-microscopy, or 'cryo-EM' - imaging samples frozen to -180oC - to show the proteasome complex in such extraordinary detail that they could view a prototype drug bound to its active sites.

The ...

This news release is available in German. Acute liver failure is a rare yet life-threatening disease for young children. It often occurs extremely rapidly, for example, when a child has a fever. Yet in around 50 percent of cases it is unclear as to why this happens. Now, a team of researchers working on an international research project headed by Technische Universität München (TUM), the Helmholtz Zentrum Munich and Heidelberg University Hospital have discovered a link between the disease and mutations in a specific gene. The researchers used whole genome ...

New research led by the University of Southampton is paving the way to protect the endangered European eel as they migrate through rivers to the ocean.

The European eel, a fish of high cultural, commercial and conservation concern, has suffered a dramatic decline over recent decades, with the number of juvenile fish returning to rivers down by over 90 per cent.

While several explanations (including overfishing, pollution and climate change) have been proposed for the cause of this demise, one of the key factors is river infrastructure, such as hydropower stations, ...

This news release is available in Japanese.

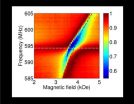

Researchers at the Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University (OIST) have identified a system that could store quantum information for longer times, which is critical for the future of quantum computing. This study was recently published in Physical Review Letters.

Quantum computing -- which aims to use particles on the atomic scale to make calculations and store the results -- has the potential to solve some key problems much faster than current computers.

To make quantum computing a reality, ...

(NEW YORK CITY - July 1, 2015) A novel synthetic hormone that makes certain skin cells produce more melanin significantly increases pain-free sun exposure in people with erythropoietic protoporphyria, a rare, genetic disorder resulting in excruciating pain within minutes of sun exposure. Two Phase III trials, conducted in Europe and in the United States by researchers at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and six other U.S. sites, showed that the duration of pain-free time in the sun and quality of life were significantly improved by treatment with afamelanotide, ...

Pregnancy and motherhood are both wonderful and worrisome times - could public health campaigns and social stereotypes be contributing to anxiety for mothers? Researchers from Monash University have identified links between perinatal anxiety and social and health messages that women are exposed to during the perinatal period, the period immediately before and after birth.

In a paper recently published in Women's Studies International Forum, Dr Heather Rowe and Professor Jane Fisher from the Jean Hailes Research Unit within the School of Public Health and Preventive Medicine ...

Unwanted, intrusive visual memories are a core feature of stress- and trauma-related clinical disorders such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), but they can also crop up in everyday life. New research shows that even once intrusive memories have been laid down, playing a visually-demanding computer game after reactivating the memories may reduce their occurrence over time.

The findings are published in Psychological Science, a journal of the Association for Psychological Science.

"This work is the first to our knowledge to show that a 'simple cognitive blockade' ...

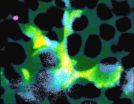

Spider-like cells inside the brain, spinal cord and eye hunt for invaders, capturing and then devouring them. These cells, called microglia, often play a beneficial role by helping to clear trash and protect the central nervous system against infection. But a new study by researchers at the National Eye Institute (NEI) shows that they also accelerate damage wrought by blinding eye disorders, such as retinitis pigmentosa. NEI is part of the National Institutes of Health.

"These findings are important because they suggest that microglia may provide a target for entirely ...