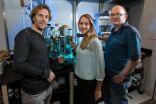

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, Johns Hopkins University Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, and Federal University of Rio de Janeiro in Brazil have designed a DNA-loaded nanoparticle that can pass through the mucus barrier covering conducting airways of lung tissue -- proving the concept, they say, that therapeutic genes may one day be delivered directly to the lungs to the levels sufficient to treat cystic fibrosis (CF), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma and other life-threatening lung diseases.

"To our knowledge, this is the first biodegradable gene delivery system that efficiently penetrates the human airway mucus barrier of lung tissue," says study author Jung Soo Suk, Ph.D., a biomedical engineer and faculty member at the Center for Nanomedicine at the Wilmer Eye Institute at Johns Hopkins. A report on the work appeared in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on June 29.

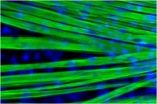

The mucus barrier protects foreign materials and bacteria from entering and/or infecting lungs. In healthy lungs, inhaled matter is typically trapped in airway mucus and subsequently swept away from the lungs via beating activities of cilia, or small, hairlike strands, to the stomach to be eventually degraded. Unfortunately, Suk notes, this essential protective mechanism also prevents many inhaled therapeutics, including gene-based medicine, from reaching their target.

His team's experiments with human airway mucus and small animals, Suk adds, were designed as a proof-of-concept study demonstrating that placing corrective or replacement genes or drugs inside a man-made biodegradable nanoparticle "wrapper" that patients inhale could penetrate the mucus barrier and one day be used to treat serious lung disorders. What's more, because a single dose might theoretically last for several months, patients would experience fewer side effects common to drugs that must be taken regularly over long stretches of time.

Suk says their work with nanoparticles grew out of failed efforts to deliver treatments to people with lung diseases. In patients with CF, for instance, they experience a buildup of excess mucus caused by impaired ciliary beating, resulting in an ideal breeding ground for chronic bacterial infection and inflammation. This pathogenic process not only worsens patients' quality of life -- and often puts patients in life-threatening situations -- but it also makes the airway mucus harder to overcome by inhaled therapeutic nanoparticles.

Most of the existing drugs for CF help clear infections but do not solve the disease's underlying problems. A couple of recently approved drugs designed to target the underlying cause of CF require daily treatment for the entire lifetime and can benefit only a subpopulation of patients with specific types of mutations. Yet this study, Suk notes, has demonstrated that delivering normal copies of CF-related genes or corrective genes via the mucus-penetrating DNA-loaded nanoparticles could mediate production of normal, "functional" proteins long term. This could eventually become an effective therapy for the lungs of patients, regardless of the mutation type.

To date, no one has been able to figure out how to efficiently deliver those genes to the lungs, Suk says, noting that experiments using deactivated viruses to carry them have proven inefficient and expensive, and could potentially lead to severe side effects. Moreover, the body could develop resistance to these virus-based delivery systems, rendering the delivery mechanism moot.

Alternatively, numerous nonviral, synthetic systems have been widely tested. However, previous research had shown that most of the nonviral, DNA-loaded nanoparticles possess positive charge that caused them to adhere to negatively charged biological environments, in this case the mucus covering the lung airways. In other words, conventional nanoparticles are too sticky to avoid unwanted off-target interactions during their journey toward the target cells. Further, these particles tend to rapidly aggregate in physiological conditions, rendering them too large to penetrate the mesh of airway mucus.

For its design, the team developed a simple method to densely coat the nanoparticles with a nonsticky polymer called PEG, neutralized the charge and created a nonsticky exterior. They showed that these nanoparticles retained their sizes at a physiological environment and are capable of rapidly penetrating human airway mucus freshly collected from patients visiting the Johns Hopkins Adult Cystic Fibrosis Program directed by Michael Boyle, a co-author of the paper. The team also made the whole delivery system biodegradable so that it would not build up inside the body.

To test whether the system provides efficient gene transfer to the lungs of animals, the researchers packed them with a gene that makes light-generating proteins once delivered into the target cells. They demonstrated that inhaled delivery of the genes via the mucus-penetrating nanoparticles resulted in widespread production of the protein to levels superior to gold-standard, nonviral platforms, including a clinically tested system. In addition, they showed that the treated lungs lit up for up to four months after a single dosing.

"With one dose, you can get gene expression -- i.e., production of therapeutic proteins -- for several months," Suk says, adding that the nanoparticles did not appear to show any adverse effects, such as increased lung inflammation.

Suk and his team caution that more animal studies are needed to confirm and refine their proof-of-concept study, and that treatment of human disorders with nanowrapped therapies is years away.

INFORMATION:

Additional Johns Hopkins researchers include Panagiotis Mastorakos, Jane Chisholm, Eric Song, Won Kyu Choi and Justin Hanes.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under grant numbers P01 HL51811 and R01HL127413 and the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation under grant numbers HANES07XX0 and HANES15G0.

On the Web:

Nanomedicine for Respiratory Diseases

Related Articles:

Magnetic Nanoparticles Could Be Key to Effective Immunotherapy

Tiny Nanoparticles Could Make Big Impact for Patients in Need of Cornea Transplant

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Media Relations and Public Affairs

Media contacts:

Marin Hedin, (410) 502-9429, mhedin2@jhmi.edu,

Helen Jones, (410) 502-9422, hjones49@jhmi.edu