(Press-News.org) Big data sets are important tools of modern science. Mining for correlations between millions of pieces of information can reveal vital relationships or predict future outcomes, such as risk factors for a disease or structures of new chemical compounds.

These mining operations are not without risk, however. Researchers can have a tough time telling when they have unearthed a nugget of truth, or what amounts to fool's gold: a correlation that seems to have predictive value but actually does not, as it results just from random chance.

A research team that bridges academia and industry has developed a new mining tool that can help tell these nuggets apart. In a study published in Science, they have outlined a method for successively testing hypotheses on the same data set without compromising statistical assurances that their conclusions are valid.

Existing checks on this kind of "adaptive analysis," where new hypotheses based on the results of previous ones are repeatedly tested on the same data, can only be applied to very large datasets. Acquiring enough data to run such checks can be logistically challenging or cost prohibitive.

The researchers' method could increase the power of analysis done on smaller datasets, by flagging ways researchers can come to a "false discovery," where a finding appears to be statistically significant but can't be reproduced in new data.

For each hypothesis that needs testing, it could act as a check against "overfitting", where predictive trends only apply to a given dataset and can't be generalized.

The study was conducted by Cynthia Dwork, distinguished scientist at Microsoft Research, Vitaly Feldman, research scientist at IBM's Almaden Research Center, Moritz Hardt, research scientist at Google, Toniann Pitassi, professor in the Department of Computer Science at the University of Toronto, Omer Reingold, principle researcher at Samsung Research America, and Aaron Roth, assistant professor in the Department of Computer and Information Science in the University of Pennsylvania's School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Adaptive analysis, where multiple tests on a dataset are combined to increase their predictive power, is an increasingly common technique. It also has the ability to deceive.

Imagine receiving an anonymous tip via email one morning saying the price of a certain stock will rise by the end of the day. At the closing bell, the tipster's prediction is borne out, and another prediction is made. After a week of unbroken success, the tipster begins charging for his proven prognostication skills.

Many would be inclined to take up the tipster's offer and fall for this scam. Unbeknownst to his victims, the tipster started by sending random predictions to thousands of people, and only repeated the process with the ones that ended up being correct by chance. While only a handful of people might be left by the end of the week, each sees what appears to be a powerfully predictive correlation that is actually nothing more than a series of lucky coin-flips.

In the same way, "adaptively" testing many hypotheses on the same data, each new one influenced by the last, can make random noise seem like a signal: what is known as a false discovery. Because the correlations of these false discoveries are idiosyncratic to the dataset in which they were generated, they can't be reproduced when other researchers try to replicate them with new data.

The traditional way to check that a purported signal is not just coincidental noise is to use a "holdout." This is a data set that is kept separate while the bulk of the data is analyzed. Hypotheses generated about correlations between items in the bulk data can be tested on the holdout; real relationships would exist in both sets, while false ones would fail to be replicated.

The problem with using holdouts in that way is that, by nature, they can only be reused if each hypothesis is independent of each other. Even a few additional hypotheses chained off one another could quickly lead to false discovery.

To this end, the researchers developed a tool known as a "reusable holdout." Instead of testing hypothesis on the holdout set directly, scientists would query it through a "differentially private" algorithm.

The "different" in its name is a reference to the guarantee that a differentially private algorithm makes. Its analyses should remain functionally identical when applied to two different datasets: one with and one without the data from any single individual. This means that any findings that would rely on idiosyncratic outliers of a given set would disappear when looking at data through a differentially private lens.

To test their algorithm, the researchers performed adaptive data analysis on a set rigged so that it contained nothing but random noise. The set was abstract, but could be thought of as one that tested 20,000 patients on 10,000 variables, such as variants in their genomes, for ones that were predictive of lung cancer.

Though, by design, none of the variables in the set were predictive of cancer, reuse of a holdout set in the standard way showed that 500 of them had significant predictive power. Performing the same analysis with the researchers' reusable holdout tool, however, correctly showed the lack of meaningful correlations.

An experiment with a second rigged dataset depicted a more realistic scenario. There, some of the variables did have predictive power, but traditional holdout use created a combination of variables with wildly overestimated this power. The reusable holdout tool correctly identified the 20 that had true statistical significance.

Beyond pointing out the dangers of accidental overfitting, the reusable holdout algorithm could warn users when they were exhausting the validity of a dataset. This is a red flag for what is known as "p-hacking," or intentionally gaming the data to get a publishable level of significance.

Implementing the reusable holdout algorithm will allow scientists to generate stronger, more generalizable findings from smaller amounts of data.

INFORMATION:

Autopsies of nearly every patient with the lethal neurodegenerative disorder amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and many with frontotemporal dementia (FTD), show pathologists telltale clumps of a protein called TDP-43. Now, working with mouse and human cells, Johns Hopkins researchers report they have discovered the normal role of TDP-43 in cells and why its abnormal accumulation may cause disease.

In an article published Aug. 7 in Science, the researchers say TDP-43 is normally responsible for keeping unwanted stretches of the genetic material RNA, called cryptic ...

For more than 20 years, Caltech geologist Jean-Philippe Avouac has collaborated with the Department of Mines and Geology of Nepal to study the Himalayas--the most active, above-water mountain range on Earth--to learn more about the processes that build mountains and trigger earthquakes. Over that period, he and his colleagues have installed a network of GPS stations in Nepal that allows them to monitor the way Earth's crust moves during and in between earthquakes. So when he heard on April 25 that a magnitude 7.8 earthquake had struck near Gorkha, Nepal, not far from Kathmandu, ...

Case Western Reserve scientists may have uncovered a molecular mechanism that sets into motion dangerous infection in the feet and hands often occurring with uncontrolled diabetes. It appears that high blood sugar unleashes destructive molecules that interfere with the body's natural infection-control defenses.

The harmful molecules -- dicarbonyls -- are breakdown products of glucose that interfere with infection-controlling antimicrobial peptides known as beta-defensins. The Case Western Reserve team discovered how two dicarbonyls -- methylglyoxal (MGO) and glyoxal (GO) ...

ROSEMONT, Ill.--According to a new study in the Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (JAAOS), imaging studies necessary to diagnose traumatic injuries sustained by pregnant women are safe when used properly.

During pregnancy, approximately 5 to 8 percent of women sustain traumatic injuries, including fractures and muscle tears. To help evaluate and manage these injuries, orthopaedic surgeons often recommend radiographs and other imaging studies. "While care should be taken to protect the fetus from exposure, most diagnostic studies are generally safe, ...

Women experience more emotional pain following a breakup, but they also more fully recover, according to new research from Binghamton University.

Researchers from Binghamton University and University College London asked 5,705 participants in 96 countries to rate the emotional and physical pain of a breakup on a scale of one (none) to 10 (unbearable). They found that women tend to be more negatively affected by breakups, reporting higher levels of both physical and emotional pain. Women averaged 6.84 in terms of emotional anguish versus 6.58 in men. In terms of physical ...

PITTSBURGH-- In the era of launching Kickstarter campaigns to pay for just about anything, Carnegie Mellon University ethicists warn that the trend of patients funding their own clinical trials may do more harm than good.

CMU's Danielle Wenner and Alex John London and McGill University's Jonathan Kimmelman co-wrote a column in Cell Stem Cell outlining how patient-funded trials may seem like a beneficial new way to involve more patients in research and establish new funding opportunities, but instead they threaten scientific rigor, relevance, efficiency and fairness.

"Patient-funded ...

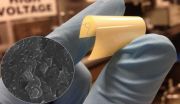

Easily manufactured, low cost, lightweight, flexible dielectric polymers that can operate at high temperatures may be the solution to energy storage and power conversion in electric vehicles and other high temperature applications, according to a team of Penn State engineers.

"Ceramics are usually the choice for energy storage dielectrics for high temperature applications, but they are heavy, weight is a consideration and they are often also brittle," said Qing Wang, professor of materials science and engineering, Penn State. "Polymers have a low working temperature and ...

Researchers at USC have developed a yeast model to study a gene mutation that disrupts the duplication of DNA, causing massive damage to a cell's chromosomes, while somehow allowing the cell to continue dividing.

The result is a mess: Zombie cells that by all rights shouldn't be able to survive, let alone divide, with their chromosomes shattered and strung out between tiny micronuclei. Sometimes they're connected to each other by ultrafine DNA bridges. (Imagine tearing apart a hot pizza - these DNA bridges are like strings of cheese still draping between the separated ...

WASHINGTON - The Society for Public Health Education (SOPHE) announces the publication of a Health Education & Behavior theme section devoted to the latest research on domestic violence prevention and the effectiveness of community coalitions in 19 states to prevent and reduce intimate partner violence. The theme section "DELTA PREP" (Domestic Violence Prevention Enhancement and Leadership Through Alliances and Preparing and Raising Expectations for Prevention) presents findings from a multi-site project supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) ...

Abusive men put female partners at greater sexual risk, study finds

Abusive and controlling men are more likely to put their female partners at sexual risk, and the level of that risk escalates along with the abusive behavior, a UW study found.

Published in the Journal of Sex Research in July, the study looked at patterns of risky sexual behavior among heterosexual men aged 18 to 25, including some who self-reported using abusive and/or controlling behaviors in their relationships and others who didn't.

The research found that men who were physically and sexually ...