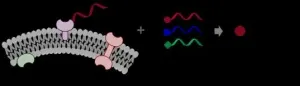

That was the intent behind a new study, led by researchers at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine, examining infection with the parasite Cryptosporidium. When the team looked for the very first "danger" signals emitted by a host infected with the parasite, they traced them not to an immune cell, as might have been expected, but to epithelial cells lining the intestines, where Cryptosporidium sets up shop during an infection. Known as enterocytes, these cells take up nutrients from the gut, and here they were shown to alert the body to danger via the molecular receptor NLRP6, which is a component of what's known as the inflammasome.

"You can think about the inflammasome as an alarm system in a house," says Boris Striepen, a professor in the Department of Pathobiology at Penn Vet and senior author on the paper, which is publishing in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. "It has various components--like a camera that watches the door, and sensors on the windows--and once triggered it amplifies those first signals to warn of danger and send a call for help. Cells have these different components as well, and now we've provided maybe the clearest example yet of how a particular receptor in the gut is acting as a sensor for an important intestinal infection."

Typically, Striepen says, researchers have focused on immune cells, like macrophages and dendritic cells, as being the first to detect foreign invaders, but this new finding underscores that cells not normally thought of as part of the immune system--in this case intestinal epithelial cells--are playing key roles in how how an immune response gets launched.

"There is a growing body of literature that is really appreciating what epithelial cells are doing to help the immune system sense pathogens," says Adam Sateriale, first author on the paper who was a postdoc in Striepen's lab and now leads his own lab at the Francis Crick Institute in London. "They seem to be a first line of defense against infection."

Striepen's lab has devoted considerable attention to Cryptosporidium, which is a leading cause of diarrheal disease that can be deadly in young children in resource-poor areas around the world. Cryptosporidium is also a threat to people in well-resourced environments, causing half of all water-borne disease outbreaks in the United States. In veterinary medicine, it's known for infecting calves, stunting their growth. These infections have no effective treatment and no vaccine.

In the current work, Striepen, Sateriale and colleagues took advantage of a naturally occurring species of mouse Cryptosporidium that they recently discovered mimics human infection in many respects. While the researchers knew T cells help control the parasite in later stages of infection, they began looking for clues as to what happens first.

One important clue is the unfortunate linkage between malnutrition and Cryptosporidium infection. Early infection with Cryptosporidium and the inflammation of the intestine that goes along with it predisposes children to malnutrition and stunted growth; at the same time, children who are malnourished are more susceptible to infection. This can lead to a downward spiral, putting children at greater risk of deadly infections. The mechanisms behind this phenomenon are not well understood.

"That led us to think that maybe some of the danger-sensing mechanisms that can drive inflammation in the gut also play a role in the larger context of this infection," adds Striepen.

Together these linkages inspired the research team to look more closely at the inflammasome and its impact on the course of infection in their mouse model. They did so by removing a key component of the inflammasome, an enzyme called caspase-1. "It turns out that animals that are missing this had much higher levels of infection," Sateriale says.

Further work demonstrated that mice lacking caspase-1 just in intestinal epithelial cells suffered infections as high as those lacking it completely, demonstrationg the crucial role of the epithelial cell.

Consistent with this idea, the Penn Vet-led team showed that, out of a variety of candidate receptors, only loss of the NLRP6 receptor lead to failure to control the infection. NLRP6 is a receptor restricted to epithelial barriers previously linked to sensing and maintaining the intestinal microbiome, bacteria that naturally colonize the gut. However, experiments revealed that mice never exposed to bacteria, and thus lacked a microbiome, also activated their inflammasome upon infection with Cryptosporidium--a sign that this aspect of danger signalling occurs in direct response to parasite infection and independent of the gut bacterial community.

To trace how triggering the intestinal inflammasome led to an effective response, the researchers looked at some of the signalling molecules, or cytokines, typically associated with inflammasome activation. They found that infection leads to release of IL-18, with those animals that lack this cytokine or the ability to release it showing more severe infection.

"And when you add back IL-18, you can rescue these mice," Sateriale says, nearly reversing the effects of infection.

Striepen, Sateriale, and colleagues believe there's a lot more work to be done to find a vaccine against Cryptosporidium. But they say their findings help illuminate important aspects of the interplay between the parasite, the immune system, and the inflammatory response, relationships that may inform these translational goals.

Moving forward, they are looking to the later stages of Cryptosporidium infection to see how the host successfully tamps it down. "Now that we understand how infection is detected, we'd like to understand the mechanisms by which it is controlled," Sateriale says. "After the system senses a parasite, what is done to restrict their growth and kill them?"

INFORMATION:

Striepen and Sateriale coauthors on the paper were Penn Vet's Jodi A. Gullicksrud, Julie B. Engiles, Briana McLeod, Emily Dugler, Jorge Henao-Mejia, Igor E. Brodsky, and Christopher Hunter, and Yale University's Ting Zhou and Aaron M. Ring.

Boris Striepen is a professor in the Department of Pathobiology in the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine.

Adam Sateriale is a group leader at the Francis Crick Institute. He completed a postdoctoral fellowship in the Striepen laboratory.

The study was supported by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation (Grant 1183177) and the National Institutes of Health (grants AI148249, AI137442, and AI055400).