Hospitals must help their own COVID long-haulers recover, experts argue

Hospitals must do more to accommodate their recovering workers' needs -- or risk losing them at a time when they're needed most, argues a multidisciplinary team of experts.

2021-01-12

(Press-News.org) BOSTON -- By mid-November, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention had reported that 218,439 health care workers in the U.S. had been infected with COVID-19 -- a likely underestimate due to incomplete data from states. About 3% to 4% of health care personnel who recover from coronavirus infection are expected to become "COVID long-haulers" as they cope with debilitating symptoms 12 to 18 months after the acute stage of the infection clears.

"As COVID-19 surges again, hospitals are facing a shortage of skilled frontline providers who can meet the relentless demands of caring for these patients," says Zeina N. Chemali, MD, MPH, a psychiatrist and neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and senior author of an article in Lancet Respiratory Medicine on the challenges of health care workers who are COVID long-haulers. "Providers struggling with post-COVID complications will further strain the health care system unless medical institutions step up to support those who have sacrificed their health during the pandemic." Chemali directs MGH's McCance Center for Brain Health and the neuropsychiatry clinic, which treat COVID survivors with lingering symptoms.

Long-term complications of COVID can affect multiple organs in the body. Some people suffer neuropsychiatric complaints, such as overwhelming fatigue, brain fog, persistent headaches, altered sleep, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder and difficulty concentrating. They may also have cardiopulmonary symptoms -- fatigue after exertion, shortness of breath, persistent cough, heart arrhythmias, fluctuating blood pressure and fainting. Currently there are no curative treatments for post-COVID syndromes; therapy focuses on alleviating symptoms and coping strategies. Long-term complications of COVID can occur even in mild cases of the virus.

Chemali and her colleagues are calling for medical institutions to support and promote the safe return to work for all health care workers disabled from lingering symptoms of COVID. Current national return-to-work guidelines focus primarily on health care workers' infection status, leaving institutions to establish their own policies or for employees to opt for medical or disability leave. While some institutions have made accommodations for health care personnel as they return to work post-COVID, the measures may not apply to all affected workers, exacerbating existing social inequities. In addition, the culture of medicine elevates duty to patients over personal needs, leaving behind the wellness of its workforce.

The authors recommend that multidisciplinary teams at medical institutions be charged with devising back-to-work strategies for health care workers with long-term COVID symptoms. These strategies might include a gradual reintroduction into the work force, limiting shifts so natural circadian rhythms aren't disrupted, mandating frequent breaks and reducing workloads to prevent fatigue, and partnering with other providers to provide oversight during complex tasks and to share clinical responsibilities.

In addition, the authors are advocating for Congress to acknowledge the health issues and needs of long-hauler health care providers and for the new Biden administration to create funding to support health care workers as they recover from COVID. Previous U.S. government initiatives, such as the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, provided financial support to medical practices and hospitals struggling during the pandemic, but essential hospital workers disabled by the virus didn't individually benefit from the funding, says Chemali.

Medical institutions and society have a moral obligation to support health care veterans of the COVID war, says Chemali, who studies mental health and neurological disorders among refugees and in people living in war zones. "Whether frontline providers are taking care of people in war zones or in hospitals filled with patients with COVID, they are working in dangerous, very uncertain and stressful environments," says Chemali. "And yet they continue to perform their mission despite being overworked and burned out, which decreases their resilience and perhaps their immunity to the virus itself. We need to do better by health care workers who get sick with COVID. If we don't help survivors of COVID recover and return to work as providers, institutions risk losing even more of their skilled personnel, who will succumb to the exhaustion and stress caused by this relentless COVID tsunami."

INFORMATION:

Chemali is director of the Neuropsychiatry Clinic at MGH, unit chief of the McCance Center for Brain Health, and associate professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at Harvard Medical School (HMS). Nathan C. Praschan, MD, Sylvia Elena Josephy, MD, and David Dongkyung Kim, MD, are clinical fellows in Neuropsychiatry at MGH. Michael Kritzer-Cheren, MD, PhD, is an instructor in Psychiatry at HMS. Shibani Mukerji, MD, PhD, is associate director of the Neuro-infectious Diseases Unit at MGH and assistant professor of Neurology at HMS. Amy Newhouse, MD, is an instructor in Psychiatry at HMS. Marie Pasinski, MD, is assistant professor of Neurology at HMS and faculty at the McCance Center for Brain Health.

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-12

A group of scientists from Russia, China, and the United States predicted and then experimentally obtained barium superhydrides' new unusual superconductors. The study was published in Nature Communications.

Chemists and physicists have been hunting down room-temperature superconductors since the first half of the 20th century. Initially, high hopes were placed on metallic hydrogen, but solid metallic hydrogen can become superconducting only at extremely high pressures of several million atmospheres, as it later transpired. Chemists then tried adding other elements to hydrogen in the hope of attaining superconductivity by stabilizing the metallic state under less challenging conditions. ...

2021-01-12

Typically characterized as poisonous, corrosive and smelling of rotten eggs, hydrogen sulfide's reputation may soon get a face-lift thanks to Johns Hopkins Medicine researchers. In experiments in mice, researchers have shown the foul-smelling gas may help protect aging brain cells against Alzheimer's disease. The discovery of the biochemical reactions that make this possible opens doors to the development of new drugs to combat neurodegenerative disease.

The findings from the study are reported in the Jan. 11 issue of the Proceedings of the National Academies of Sciences.

"Our new data firmly link aging, neurodegeneration and cell signaling using hydrogen sulfide and other gaseous molecules within the cell," says Bindu Paul, M.Sc., Ph.D., faculty ...

2021-01-12

Climate changes prompt many important questions. Not least how it affects animals and plants: Do they adapts, gradually migrate to different areas or become extinct? And what is the role played by human activities? This applies not least to Greenland and the rest of the Artic, which are expected to see the greatest effects of climate changes.

'We know surprisingly little about marine species and ecosystems in the Arctic, as it is often costly and difficult to do fieldwork and monitor the biodiversity in this area', says Associate Professor of marine mammals and instigator of the study ...

2021-01-12

Researchers from Skoltech and their colleagues have optimized data analysis for a common method of studying the 3D structure of DNA in single cells of a Drosophila fly. The new approach allows the scientists to peek with greater confidence into individual cells to study the unique ways DNA is packaged there and get closer to understanding this crucial process's underlying mechanisms. The paper was published in the journal Nature Communications.

The reason a roughly two-meter-long strand of DNA fits into the tiny nucleus of a human cell is that chromatin, a complex of DNA and proteins, packages it ...

2021-01-12

A study of students at seven public universities across the United States has identified risk factors that may place students at higher risk for negative psychological impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Factors associated with greater risk of negative impacts include the amount of time students spend on screens each day, their gender, age and other characteristics.

Research has shown many college students faced significant mental health challenges going into the COVID-19 pandemic, and experts say the pandemic has added new stressors. The findings, published in the journal PLOS ONE, could help experts tailor services ...

2021-01-12

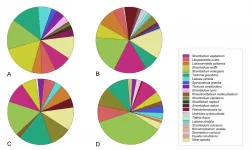

Announcing a new publication for Marine Life Science & Technology journal. In this research article the authors Hungchia Huang, Jinpeng Yang, Shixiang Huang, Bowei Gu, Ying Wang, Lei Wang and Nianzhi Jiao from Xiamen University, Xiamen, China and Sun Yat-Sen University, Guangzhou, China consider the spatial distribution of planktonic ciliates in the western Pacific Ocea: along a transect from Shenzhen (China) to Pohnpei (Micronesia).

Planktonic ciliates have been recognized as major consumers of nano- and picoplankton in pelagic ecosystems, playing pivotal roles in the transfer ...

2021-01-12

COLUMBIA, Mo. - As a former school nurse in the Columbia Public Schools, Gretchen Carlisle would often interact with students with disabilities who took various medications or had seizures throughout the day. At some schools, the special education teacher would bring in dogs, guinea pigs and fish as a reward for good behavior, and Carlisle noticed what a calming presence the pets seemed to be for the students with disabilities.

Now a research scientist at the MU Research Center for Human-Animal Interaction (ReCHAI) in the MU College of Veterinary Medicine, Carlisle studies the benefits that companion animals can have on families. While there is plenty of ...

2021-01-12

New Orleans, LA - Catherine O'Neal, MD, Assistant Professor of Clinical Medicine at LSU Health New Orleans School of Medicine's branch campus in Baton Rouge, is a co-author of a paper reporting that shortening the length of quarantine due to COVID exposure when supported by mid-quarantine testing may increase compliance among college athletes without increasing risk. The findings are published in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's January 8, 2021 Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), available here.

CDC partnered with representatives of the NCAA conferences to analyze retrospective data collected by participating colleges and universities. De-identified data from a total of 620 ...

2021-01-12

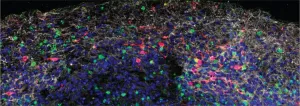

Gut microbes passed from female mice to their offspring, or shared between mice that live together, may influence the animals' bone mass, says a new study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that treatments which alter the gut microbiome could help improve bone structure or treat conditions that weaken bones, such as osteoporosis.

"Genetics account for most of the variability in human bone density, but non-genetic factors such as gut microbes may also play a role," says lead author Abdul Malik Tyagi, Assistant Staff Scientist at the Division of Endocrinology, Metabolism, and Lipids at Emory Microbiome Research Center, Emory University, Georgia, US. "We wanted to investigate the influence of the microbiome on skeletal growth and bone mass development."

To ...

2021-01-12

Using both mouse and human brain tissue, researchers at Yale School of Medicine have discovered that SARS-CoV-2 can directly infect the central nervous system and have begun to unravel some of the virus's effects on brain cells. The study, published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine (JEM), may help researchers develop treatments for the various neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19.

Though COVID-19 is considered to primarily be a respiratory disease, SARS-CoV-2 can affect many other organs in the body, including, in some patients, the central nervous system, where infection is associated with ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Hospitals must help their own COVID long-haulers recover, experts argue

Hospitals must do more to accommodate their recovering workers' needs -- or risk losing them at a time when they're needed most, argues a multidisciplinary team of experts.