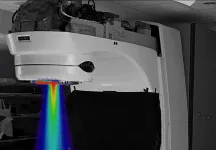

(Press-News.org) LEBANON, NH - A joint team of researchers from Radiation Oncology at Dartmouth's and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC), Dartmouth Engineering, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Department of Surgery have developed a method to convert a standard linear accelerator (LINAC), used for delivery of radiation therapy cancer treatment, to a FLASH ultra-high-dose rate radiation therapy beam. The work, entitled "Electron FLASH Delivery at Treatment Room Isocenter for Efficient Reversible Conversion of a Clinical LINAC," is newly published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology & Physics.

The exceptionally high dose rate is 3,000 times higher than normal therapy treatment (300 Gray per second vs. 0.1 Gray per second, Gray being a standard unit measuring absorbed radiation). Instead of treatment over 20 seconds, an entire treatment is completed in 6 milliseconds, giving the therapy its nickname, "FLASH." "These high dose rates have been shown to protect normal tissues from excess damage while still having the same treatment effect on tumor tissues, and may be critically important for limiting radiation damage in patients receiving radiation therapy," says Brian Pogue, PhD, Co-Director of NCCC's Translational Engineering in Cancer Research Program and co-author on the project.

While the team awaits news of potential funding from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), early pilot funding from NCCC and Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering allowed for prototyping of the converted LINAC. Pre-clinical testing of the beam began in August and has already provided key data on its potential for different tumor plans. "This is the first such beam in New England and on the east coast, and we believe it is the first reversible FLASH beam on a clinically used LINAC where the beam can be used in the conventional geometry with patients on the treatment couch," says Pogue.

The FLASH beam is currently being used in preclinical studies on both experimental animal tumors as well as in clinical veterinary treatments, to study the normal tissue-sparing effects and how to maximize the value. The research group has expanded to involve physicians in clinical radiation oncology and dermatology, designing what they hope will be the first human safety trial with FLASH radiotherapy at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, treating patients advanced skin lesions that cannot be removed surgically.

INFORMATION:

The published project was led by researchers Rongxiao Zhang, PhD, Petr Bruza, PhD, David Gladstone, ScD, and P. Jack Hoopes, DVM, with work done by Dartmouth Engineering PhD students and first authors Ronny Rahman and Ramish Ashraf, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock engineering from Lawrence Thompson and Chad Dexter.

Brian W. Pogue, PhD, is Co-Director of the Translational Engineering in Cancer Research Program at Dartmouth's and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center, MacLean Professor of Engineering at Dartmouth's Thayer School of Engineering, Professor of Surgery at Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, and President and Co-Founder of DoseOptics, LLC, which develops camera systems and software for radiotherapy imaging of Cherenkov light for dosimetry. His research interests include optics in medicine, biomedical imaging to guide cancer therapy, molecular-guided surgery, dose imaging in radiation therapy, Cherenkov light imaging, image-guided spectroscopy of cancer, photodynamic therapy, and modeling of tumor pathophysiology and contrast.

About Norris Cotton Cancer Center

Norris Cotton Cancer Center, located on the campus of Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) in Lebanon, NH, combines advanced cancer research at Dartmouth College's Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, NH with the highest level of high-quality, innovative, personalized, and compassionate patient-centered cancer care at DHMC, as well as at regional, multi-disciplinary locations and partner hospitals throughout NH and VT. NCCC is one of only 51 centers nationwide to earn the National Cancer Institute's prestigious "Comprehensive Cancer Center" designation, the result of an outstanding collaboration between DHMC, New Hampshire's only academic medical center, and Dartmouth College. Now entering its fifth decade, NCCC remains committed to excellence, outreach and education, and strives to prevent and cure cancer, enhance survivorship and to promote cancer health equity through its pioneering interdisciplinary research. Each year the NCCC schedules 61,000 appointments seeing nearly 4,000 newly diagnosed patients, and currently offers its patients more than 100 active clinical trials.

About Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health

Dartmouth-Hitchcock Health (D-HH), New Hampshire's only academic health system and the state's largest private employer, serves a population of 1.9 million across northern New England. D-H provides access to more than 2,000 providers in almost every area of medicine, delivering care at its flagship hospital, Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center (DHMC) in Lebanon, NH. DHMC was named again in 2020 as the #1 hospital in New Hampshire by U.S. News & World Report, and recognized for high performance in 9 clinical specialties and procedures. Dartmouth-Hitchcock also includes the Norris Cotton Cancer Center, one of only 51 NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Centers in the nation; the Children's Hospital at Dartmouth-Hitchcock, the state's only children's hospital; affiliated member hospitals in Lebanon, Keene, and New London, NH, and Windsor, VT, and Visiting Nurse and Hospice for Vermont and New Hampshire; and 24 Dartmouth-Hitchcock clinics that provide ambulatory services across New Hampshire and Vermont. The D-H system trains nearly 400 residents and fellows annually, and performs world-class research, in partnership with the Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth and the White River Junction VA Medical Center in White River Junction, VT.

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from the Russian Quantum Center revealed a significant role of nuclear quantum effects in the polarization of alcohol in an external electric field. Their research findings are published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry.

Molecular liquids, such as water or alcohols, are known to be polar. Polarity results from the charge separation mechanism, the microscopic description of which still bears some open questions. In fact, the basic description of the polarization rests on a hundred-years-old concept: the dielectric polarization is connected to the molecular dipole moment due to their hydroxyl ...

WASHINGTON, Jan. 19, 2020 -- What makes breast milk so good for babies? In this episode of Reactions, our host, Sam, chats with chemist Steven Townsend, Ph.D., who's trying to figure out which sugar molecules in breast milk make it so unique and difficult to mimic: https://youtu.be/o4_npLDyyUw.

INFORMATION:

Reactions is a video series produced by the American Chemical Society and PBS Digital Studios. Subscribe to Reactions at http://bit.ly/ACSReactions and follow us on Twitter @ACSReactions.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS' mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and its people. The Society is a global leader in providing access ...

Two international studies confirm that for the majority of patients with respiratory infections who lose the sense of smell, this is due to COVID-19. The disease also often results in both loss of taste and the other senses in the mouth. A researcher from Aarhus University has contributed to the new results.

If you have had COVID-19, then forget about enjoying the smell of freshly made coffee. At any rate, two major international studies document that there is frequently a loss of smell and that this often lasts for a long time in cases of COVID-19

Alexander Wieck Fjaeldstad, is associate professor in olfaction and gustation at Aarhus University, and is behind the Danish part of the study.

The study ...

In a large-scale study of Danish children and young people, researchers from Aarhus University have for the first time found genetic variants that increase the risk of nocturnal enuresis - commonly known as bedwetting or nighttime incontinence. The findings provide completely new insights into the processes in the body causing this widespread phenomenon.

Researchers have long known that nighttime incontinence is a highly heritable condition. Children who wet the bed at night often have siblings or parents who either suffer from or have suffered from the same condition. ...

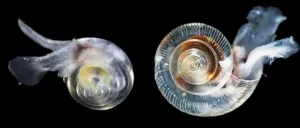

Shelled pteropods, microscopic free-swimming sea snails, are widely regarded as indicators for ocean acidification because research has shown that their fragile shells are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity.

A new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that pteropods sampled off the coasts of Washington and Oregon made thinner shells than those in offshore waters. Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, by a team of Dutch and American scientists, ...

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory and collaborators at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have discovered a new light-induced switch that twists the crystal lattice of the material, switching on a giant electron current that appears to be nearly dissipationless. The discovery was made in a category of topological materials that holds great promise for spintronics, topological effect transistors, and quantum computing.

Weyl and Dirac semimetals can host exotic, nearly dissipationless, electron conduction properties that take advantage of the unique state in the crystal lattice and electronic structure of the material that protects the electrons from doing so. These anomalous electron transport channels, ...

Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as ...

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

Scientists are urging global policymakers and funders to think of fish as a solution to food insecurity and malnutrition, and not just as a natural resource that provides income and livelihoods, in a newly-published paper in the peer-reviewed journal Ambio. Titled "Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding," the paper argues for viewing fish from a food systems perspective to broaden the conversation on food and nutrition security and equity, especially as global food systems will face increasing threats from climate change.

The "Fish as Food" paper, authored by scientists and policy experts from Michigan State University, Duke ...

HOUSTON - (Jan. 19, 2021) - Microscopic bubbles can tell stories about Earth's biggest volcanic eruptions and geoscientists from Rice University and the University of Texas at Austin have discovered some of those stories are written in nanoparticles.

In an open-access study published online in Nature Communications, Rice's Sahand Hajimirza and Helge Gonnermann and UT Austin's James Gardner answered a longstanding question about explosive volcanic eruptions like the ones at Mount St. Helens in 1980, the Philippines' Mount Pinatubo in 1991 or Chile's Mount Chaitén in 2008.

Geoscientists have long sought to use tiny bubbles in erupted lava and ash to reconstruct some of the conditions, ...