How dietary choice influences lifespan in fruit flies

Giving flies a choice of foods changes the chemical messaging in their brain that is responsible for coordinating metabolism, shortening their lifespan as a result

2021-01-19

(Press-News.org) Having a choice of foods may accelerate aging and shorten the lifespan of fruit flies, according to a study published today in the open-access eLife journal.

While early experiments have shown that calorie restriction can extend lifespan, the current study adds to the growing body of evidence that suggests other diet characteristics besides calories may also influence aging and lead to earlier death.

"It has been recognised for nearly a century that diet modulates aging," says first author Yang Lyu, Postdoctoral Fellow at the Department of Molecular & Integrative Physiology, University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, US. "For our study, we wanted to see if having a choice of foods affects metabolism and lifespan in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster."

Lyu and colleagues began by giving fruit flies either a diet of brewer's yeast and sugar mixed together, or a choice of the two nutrients separately. They found that having the choice between foods changed the flies' behaviour and metabolism, and shortened their lifespan, independent of how much they ate.

These changes indicated that the flies have distinct neural and metabolic states when given a choice between foods, in comparison to when they are presented with one combined food option. Further experiments by the team showed that a choice between meals causes rapid metabolic reprogramming, and this is controlled by an increase in serotonin 2A receptor signalling in the brain.

The researchers then inhibited the expression of an enzyme called glutamate dehydrogenase, which is key to these metabolic changes, and found that doing so reversed the life-shortening effects of food choice on the flies.

"Our results reveal a mechanism of aging caused by fruit flies and other organisms needing to evaluate nutrient availability to improve their survival and wellbeing," Lyu says.

Since many of the same metabolic pathways also exist in humans, the authors say it is possible that similar mechanisms may be involved in human aging. But more studies will be needed to confirm this.

"It could be that the act of making decisions about food itself is costly to the flies," concludes senior author Scott Pletcher, the William H. Howell Collegiate Professor of Physiology, and Research Professor at the Institute of Gerontology, University of Michigan Medical School. "We know that in humans, having many choices can be stressful. But while short-term stress can be beneficial, chronic stress is often detrimental to lifespan and health."

INFORMATION:

Reference

The paper 'Serotonin 2A receptor signaling coordinates central metabolic processes to modulate aging in response to nutrient choice' can be freely accessed online at https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.59399. Contents, including text, figures and data, are free to reuse under a CC BY 4.0 license.

This study will be published as part of eLife's upcoming Special Issue on aging, geroscience and longevity. For more information, see https://elifesciences.org/inside-elife/4f706531/special-issue-call-for-papers-in-aging-geroscience-and-longevity.

Media contact

Emily Packer, Media Relations Manager

eLife

e.packer@elifesciences.org

01223 855373

About eLife

eLife is a non-profit organisation created by funders and led by researchers. Our mission is to accelerate discovery by operating a platform for research communication that encourages and recognises the most responsible behaviours. We work across three major areas: publishing, technology and research culture. We aim to publish work of the highest standards and importance in all areas of biology and medicine, including Genetics and Genomics, while exploring creative new ways to improve how research is assessed and published. We also invest in open-source technology innovation to modernise the infrastructure for science publishing and improve online tools for sharing, using and interacting with new results. eLife receives financial support and strategic guidance from the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation, the Max Planck Society and Wellcome. Learn more at https://elifesciences.org/about.

To read the latest Genetics and Genomics research published in eLife, visit https://elifesciences.org/subjects/genetics-genomics.

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-01-19

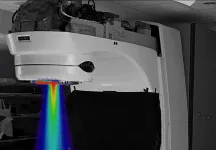

LEBANON, NH - A joint team of researchers from Radiation Oncology at Dartmouth's and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Norris Cotton Cancer Center (NCCC), Dartmouth Engineering, and Dartmouth-Hitchcock's Department of Surgery have developed a method to convert a standard linear accelerator (LINAC), used for delivery of radiation therapy cancer treatment, to a FLASH ultra-high-dose rate radiation therapy beam. The work, entitled "Electron FLASH Delivery at Treatment Room Isocenter for Efficient Reversible Conversion of a Clinical LINAC," is newly published online in the International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology & Physics.

The exceptionally high dose rate is 3,000 times higher than normal therapy treatment (300 Gray per second vs. 0.1 Gray per second, Gray being a standard ...

2021-01-19

Skoltech scientists and their colleagues from the Russian Quantum Center revealed a significant role of nuclear quantum effects in the polarization of alcohol in an external electric field. Their research findings are published in The Journal of Physical Chemistry.

Molecular liquids, such as water or alcohols, are known to be polar. Polarity results from the charge separation mechanism, the microscopic description of which still bears some open questions. In fact, the basic description of the polarization rests on a hundred-years-old concept: the dielectric polarization is connected to the molecular dipole moment due to their hydroxyl ...

2021-01-19

WASHINGTON, Jan. 19, 2020 -- What makes breast milk so good for babies? In this episode of Reactions, our host, Sam, chats with chemist Steven Townsend, Ph.D., who's trying to figure out which sugar molecules in breast milk make it so unique and difficult to mimic: https://youtu.be/o4_npLDyyUw.

INFORMATION:

Reactions is a video series produced by the American Chemical Society and PBS Digital Studios. Subscribe to Reactions at http://bit.ly/ACSReactions and follow us on Twitter @ACSReactions.

The American Chemical Society (ACS) is a nonprofit organization chartered by the U.S. Congress. ACS' mission is to advance the broader chemistry enterprise and its practitioners for the benefit of Earth and its people. The Society is a global leader in providing access ...

2021-01-19

Two international studies confirm that for the majority of patients with respiratory infections who lose the sense of smell, this is due to COVID-19. The disease also often results in both loss of taste and the other senses in the mouth. A researcher from Aarhus University has contributed to the new results.

If you have had COVID-19, then forget about enjoying the smell of freshly made coffee. At any rate, two major international studies document that there is frequently a loss of smell and that this often lasts for a long time in cases of COVID-19

Alexander Wieck Fjaeldstad, is associate professor in olfaction and gustation at Aarhus University, and is behind the Danish part of the study.

The study ...

2021-01-19

In a large-scale study of Danish children and young people, researchers from Aarhus University have for the first time found genetic variants that increase the risk of nocturnal enuresis - commonly known as bedwetting or nighttime incontinence. The findings provide completely new insights into the processes in the body causing this widespread phenomenon.

Researchers have long known that nighttime incontinence is a highly heritable condition. Children who wet the bed at night often have siblings or parents who either suffer from or have suffered from the same condition. ...

2021-01-19

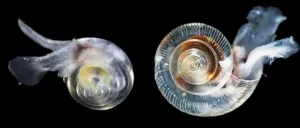

Shelled pteropods, microscopic free-swimming sea snails, are widely regarded as indicators for ocean acidification because research has shown that their fragile shells are vulnerable to increasing ocean acidity.

A new study, published in the journal Scientific Reports, shows that pteropods sampled off the coasts of Washington and Oregon made thinner shells than those in offshore waters. Along the coast, upwelling from deeper water layers brings cold, carbon dioxide-rich waters of relatively low pH to the surface. The research, by a team of Dutch and American scientists, ...

2021-01-19

Scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Ames Laboratory and collaborators at Brookhaven National Laboratory and the University of Alabama at Birmingham have discovered a new light-induced switch that twists the crystal lattice of the material, switching on a giant electron current that appears to be nearly dissipationless. The discovery was made in a category of topological materials that holds great promise for spintronics, topological effect transistors, and quantum computing.

Weyl and Dirac semimetals can host exotic, nearly dissipationless, electron conduction properties that take advantage of the unique state in the crystal lattice and electronic structure of the material that protects the electrons from doing so. These anomalous electron transport channels, ...

2021-01-19

Scientists have shown that two species of seasonal human coronavirus related to SARS-CoV-2 can evolve in certain proteins to escape recognition by the immune system, according to a study published today in eLife.

The findings suggest that, if SARS-CoV-2 evolves in the same way, current vaccines against the virus may become outdated, requiring new ones to be made to match future strains.

When a person is infected by a virus or vaccinated against it, immune cells in their body will produce antibodies that can recognise and bind to unique proteins on the virus' surface known as antigens. The immune system relies on being able to 'remember' the antigens that relate to a specific virus in order to provide immunity against it. However, in some viruses, such as ...

2021-01-19

DENVER--A study in the Journal of Thoracic Oncology (JTO) comparing surgeries performed at one Chinese hospital in 2019 with a similar date range during the COVID-19 pandemic found that routine thoracic surgery and invasive examinations were performed safely. The JTO is the official journal of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer.

Wentao Fang, MD, chief director of the Department of Thoracic Surgery, Shanghai Chest Hospital, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China and his colleagues analyzed the number of elective procedures ...

2021-01-19

Scientists are urging global policymakers and funders to think of fish as a solution to food insecurity and malnutrition, and not just as a natural resource that provides income and livelihoods, in a newly-published paper in the peer-reviewed journal Ambio. Titled "Recognize fish as food in policy discourse and development funding," the paper argues for viewing fish from a food systems perspective to broaden the conversation on food and nutrition security and equity, especially as global food systems will face increasing threats from climate change.

The "Fish as Food" paper, authored by scientists and policy experts from Michigan State University, Duke ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] How dietary choice influences lifespan in fruit flies

Giving flies a choice of foods changes the chemical messaging in their brain that is responsible for coordinating metabolism, shortening their lifespan as a result