(Press-News.org) Genetic inheritance affects the likelihood of developing breast cancer. Some genes are already known to increase cancer risk; other genes are suspected to be involved, but not to what extent. It is crucial to clarify this issue to improve prevention since it opens the way to more personalised follow-up and screening programs. A large international consortium, which includes the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), has studied 34 putative susceptibility genes on samples from 113,000 female breast cancer cases and controls, and its results confirm the importance of nine of them.

The study "defines the genes most clinically useful for inclusion on panels for breast cancer risk prediction (...), to guide genetic counselling," the authors write in the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM).

This is the most ambitious study carried out to date to shed light on the role of heredity in breast cancer, one of the most common cancers today - one out of every eight women will have it at some point in their lives.

250 researchers from dozens of institutions in more than 25 countries participated in the genetic analysis. One-third of the samples were analysed at the CNIO, with the participation of Javier Benítez, Anna González-Neira and Ana Osorio. Groups from seven other Spanish institutions also participated in the study.

Osorio, from the CNIO Human Genetics Group, stresses the importance of the information provided by this study when monitoring breast cancer patients and their families. "Genetic tests are already done on people with a family history of the disease, but in those tests we can only analyse genes of which we are certain that they affect the risk. Now we have more information, and we can improve the genetic counselling of patients and their families," the CNIO researcher says.

Low- and moderate-risk genes

It has been known for some time that the risk of developing breast cancer depends partly on genetic inheritance, but determining exactly which genes increase this risk, and how much, remains a major challenge.

The genes that confer high risk when mutated, BRCA1 and BRCA2, were already identified in the mid-1990s. Having mutations in these genes confers a cumulative risk of around 70% of developing breast cancer by the age of 80, and a risk of 40% and 20% of developing ovarian cancer for carriers of mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2, respectively. It was this strong effect that made it possible to identify these genes in families with a high incidence of cancer.

Today, genetic diagnosis alerts many patients' family members, who can then act at very early stages of cancer or even prevent its appearance. But the BRCA genes explain only a small part of all cases. In the vast majority of cases, genes are involved that confer a lower risk and that may interact with each other or with other genetic and environmental factors, which can modify the risk.

In recent years, a number of studies have identified dozens of such candidate genes that increase the risk of breast cancer to some degree, but these studies were done with relatively few patients and their results were not conclusive. It was the aim of the study now published to improve this knowledge by determining precisely which genes are involved, and to what extent they affect the risk to develop which subtype of tumour.

"Genetic testing for breast cancer susceptibility is widely used, but for many genes the evidence for association with breast cancer is weak," the authors write in NEJM, adding that the risk estimates are imprecise and that cancer subtype-specific risk estimates are lacking altogether.

"The most clinically useful genes"

The study is the result of the European project BRIDGES (Breast Cancer Risk after Diagnostic Gene Sequencing), in which the CNIO participates. The study was based on the analysis of 34 known or suspected breast cancer susceptibility genes in DNA samples from 60,400 women who had developed breast cancer and 53,400 healthy women.

The results pinpoint nine genes for which there is solid evidence of their involvement in the disease: ATM, BRCA1, BRCA2, CHEK2, PALB2, BARD1, RAD51C, RAD51D and TP53. For some of these genes, this was already known, but for others, such as RAD51C and D and BARD1, their involvement was not so well established. For all genes, more precise risk estimates can now be calculated and these estimates are tailored for each tumour subtype.

On the other hand, the study shows that about fifteen of the genes that have been used so far in some tests "are not indicative of an increased risk" for breast cancer and should therefore not be taken into account, at least at this time, in risk estimates.

However, the authors remind us that the probability of developing breast cancer is not determined by genes alone. Other risk factors such as age, hormonal history and environmental factors also play a role, which in turn are influenced by the genetic background.

"In fact," points out González-Neira, Head of the Human Genotyping - CEGEN Unit at the CNIO, "it is been already working on mathematical models that integrate current knowledge about all these factors and their interaction, which make possible to provide a good estimate of the adjusted risk for each woman and thus individualise clinical management".

The final objective is to improve prevention with much more personalised screening programmes than those currently available. Implementation of such precision medicine protocols in breast cancer will improve early diagnosis and reduce morbidity and mortality rates for this disease.

INFORMATION:

This project is funded by the European Union's Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Programme (BRIDGES), the Wellcome Trust, and Cancer Research UK. In the CNIO group, by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the National Institute of Health Carlos III.

Reference article: Breast cancer risk genes: association analysis in more than 113,000 women. Leila Dorling et al (NEJM, 2020). DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1913948

When university campuses sent students, staff and faculty members home in March, Padmini Rangamani, a professor at the University of California San Diego, suddenly found herself running her research lab remotely, teaching her classes online, and supervising her two children, ages 10 and 13, who are also learning online.

To deal with the stress the situation created, Rangamani turned to a support network of fellow female faculty members around the United States. They chatted and texted and eventually decided to write a scholarly article with recommendations for all other female principal investigators in academia.

The article, "Ten simple rules for women principal investigators during a pandemic," ...

Generating membranes using electrochemical polymerization, or electropolymerization, could provide a simple and cost-effective route to help various industries meet increasingly strict environmental regulations and reduce energy consumption.

Researchers from KAUST have produced membranes with well-defined microscopic pores by electrochemically depositing organic conjugated polymers onto highly porous electrodes. These microporous membranes have numerous applications, ranging from organic solvent nanofiltration to selective molecular transport technologies.

High-performance separation depends on membranes that are robust with well-ordered and dense microporous structures, such as zeolites and ...

Scientists from an international collaboration have found evidence of alpha particles at the surface of neutron-rich heavy nuclei, providing new insights into the structure of neutron stars, as well as the process of alpha decay.

Neutron stars are amongst the most mysterious objects in our universe. They contain extremely dense matter that is radically different from the ordinary matter surrounding us--being composed almost entirely of neutrons rather than atoms. However, in the nucleus at the center of normal atoms, matter exists at similar densities.

"Understanding the nature of matter at such extremes is important for our understanding of neutron stars, as well as the beginning, ...

COVID-19 has been spreading rapidly over the past several months, and the U.S. death toll has now reached 400,000. As evident from the age distribution of those fatalities, COVID-19 is dangerous not only for the elderly but for middle-aged adults, according to a Dartmouth-led study published in the European Journal of Epidemiology.

"For a person who is middle-aged, the risk of dying from COVID-19 is about 100 times greater than dying from an automobile accident," explains lead author Andrew Levin, a professor of economics at Dartmouth College. "Generally speaking, very few children and young adults die of COVID-19. However, the risk is progressively greater for middle-aged and older adults. The odds that ...

The bipolar membrane, a type of ion exchange membrane, is considered the pivotal material for zero emission technology. It is composed of an anode and cathode membrane layer, and an intermediate hydrolysis layer. Under reverse bias, the water molecules in the intermediate layer produce OH- and H+ by polarization.

Large-scale production of the membrane is hindered by the different expansion coefficients of the anode and cathode layers, causing the two layers easy to delaminate. Besides, the mostly used intermediate catalysts are small molecules or transition, which are instable and inefficient.

In a study published on Nature Communications, a team led by ...

BOSTON - Regular aspirin use has clear benefits in reducing colorectal cancer incidence among middle-aged adults, but also comes with some risk, such as gastrointestinal bleeding. And when should adults start taking regular aspirin and for how long?

There is substantial evidence that a daily aspirin can reduce risk of colorectal cancer in adults up to age 70. But until now there was little evidence about whether older adults should start taking aspirin.

A team of scientists set out to study this question. They were led by Andrew T. Chan MD, MPH, a gastroenterologist and chief of the Clinical and Translational Epidemiology Unit at Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH). Their report appears in JAMA Oncology.

The researchers ...

Tsukuba, Japan -- How valuable are earmuffs? The answer to this simple question can depend. What brand are they? Are they good quality? What is the weather like? Given the choice between earmuffs and suntan lotion, most people would choose to have the earmuffs on a cold winter day and the lotion on a sunny day at the beach. This ability to place different values on objects depending on the environmental context is something that we do all the time without much thought or effort. But how does it work? A new study led by Assistant Professor Jun Kunimatsu at the University of Tsukuba in Japan and Distinguished Investigator Okihide Hikosaka at the National Eye Institute (NEI) in the United States has discovered the part of ...

The elusive axion particle is many times lighter than an electron, with properties that barely make an impression on ordinary matter. As such, the ghost-like particle is a leading contender as a component of dark matter -- a hypothetical, invisible type of matter that is thought to make up 85 percent of the mass in the universe.

Axions have so far evaded detection. Physicists predict that if they do exist, they must be produced within extreme environments, such as the cores of stars at the precipice of a supernova. When these stars spew axions out into the universe, the ...

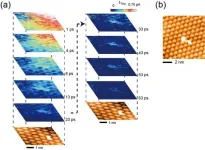

Tsukuba, Japan - A team of researchers from the Faculty of Pure and Applied Sciences at the University of Tsukuba filmed the ultrafast motion of electrons with sub-nanoscale spatial resolution. This work provides a powerful tool for studying the operation of semiconductor devices, which can lead to more efficient electronic devices.

The ability to construct ever smaller and faster smartphones and computer chips depends on the ability of semiconductor manufacturers to understand how the electrons that carry information are affected by defects. However, these motions occur on the scale of trillionths of a second, and they can only be seen with a microscope that can image individual atoms. ...

The results of a study led by Northern Arizona University and the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), an affiliate of City of Hope, suggest the immune systems of people infected with COVID-19 may rely on antibodies created during infections from earlier coronaviruses to help fight the disease.

COVID-19 isn't humanity's first encounter with a coronavirus, so named because of the corona, or crown-like, protein spikes on their surface. Before SARS-CoV-2 -- the virus that causes COVID-19 -- humans have navigated at least 6 other types of coronaviruses.

The study sought to understand how coronaviruses (CoVs) ignite the human immune system and conduct a deeper ...