(Press-News.org) LA JOLLA--A new study led by scientists at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI) suggests that T cells try to fight SARS-CoV-2 by targeting a broad range of sites on the virus--beyond the key sites on the virus's spike protein. By attacking the virus from many angles, the body has the tools to potentially recognize different SARS-CoV-2 variants.

The new research, published January 27, 2021 in Cell Report Medicine, is the most detailed analysis so far of which proteins on SARS-CoV-2 stimulate the strongest responses from the immune system's "helper" CD4+ T cells and "killer" CD8+ T cells.

"We are now armed with the knowledge of which parts of the virus are recognized by the immune system," says LJI Professor Alessandro Sette, Dr. Biol. Sci., who co-led the new study with LJI Instructor Alba Grifoni, Ph.D.

Sette and Grifoni have led research into immune responses to the virus since the beginning of the pandemic. Their previous studies, co-led by members of the LJI Coronavirus Task Force, shows that people can have a wide range of responses to the virus--some people have strong immune responses and do well. Others have disjointed immune responses and are more likely to end up in the hospital.

As COVID-19 vaccines reach more people, LJI scientists are keeping an eye on how different people build immunity to SARS-CoV-2. They are also studying how T cells could combat different variants of SARS-CoV-2. This work takes advantage of the lab's expertise in predicting and studying T cell responses to viruses such as dengue and Zika.

"This is even more important with COVID-19 because it is a global pandemic, so we need to account for immune responses in different populations," says Grifoni.

The immune system is very flexible. By re-scrambling genetic material, it can make T cells that respond to a huge range of targets, or epitopes, on a pathogen. Some T cell responses will be stronger against some epitopes than others. Researchers call the targets that prompt a strong immune cells response "immunodominant."

For the new study, the researchers examined T cells from 100 people who had recovered from SARS-CoV-2 infection. They then took a close look at the genetic sequence of the virus to separate the potential epitopes from the epitopes that these T cells would actually recognize.

Their analysis revealed that not all parts of the virus induce the same strong immune response in everyone. In fact, T cells can recognize dozens of epitopes on SARS-CoV-2, and these immunodominant sites also change from person to person. On average, each study participant had the ability to recognize about 17 CD8+ T cells epitopes and 19 CD4+ T cell epitopes.

This broad immune system response serves a few purposes. The new study shows that while the immune system often mounts a strong response against a particular site on the virus's "spike" protein called the receptor binding domain, this region is actually not as good at inducing a strong response from CD4+ helper T cells.

Without a strong CD4+ T cell response, however, people may be slow to mount the kind of neutralizing immune response that quickly wipes out the virus. Luckily, the broad immune response comes in handy, and most people have immune cells that can recognize sites other than the receptor binding domain.

Among the many epitopes they uncovered, the researchers identified several additional epitopes on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. Grifoni says this is good news. By targeting many vulnerable sites on the spike protein, the immune system would still be able to fight infection, even if some sites on the virus change due to mutations.

"The immune response is broad enough to compensate for that," Grifoni says.

Since the announcement of the fast-spreading UK variant of SARS-CoV-2 (called SARS-CoV-2 VUI 202012/01), the researchers have compared the mutated sites on that virus to the epitopes they found. Sette notes that the mutations described in the UK variant for the spike protein affect only 8% of the epitopes recognized by CD4+ T cells in this study, while 92% of the responses is conserved.

Sette emphasized that the new study is the results of months of long hours and international collaboration between labs at LJI; the University of California, San Diego; and researcher's at Australia's Murdoch University. "This was a tremendous amount of work, and we were able to do it really fast because of our collaborations," he says.

INFORMATION:

The study, "Comprehensive analysis of T cell immunodominance and immunoprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 epitopes in COVID-19 cases," was supported by the National Institutes of Health's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (AI42742 ,75N9301900065 and 75N93019C00001), the National Institutes of Health (U01 CA260541-01, AI135078, and AI036214); UCSD T32s (AI007036 and AI007384), the Jonathan and Mary Tu Foundation and the University of Genoa, Italy.

Additional study authors include first author Alison Tarke, John Sidney, Conner Kidd, Jennifer M. Dan, Sydney I. Ramirez, Esther Dawen Yu, Jose Mateus, Ricardo da Silva Antunes, Erin Moore, Paul Rubiro, Nils Methot, Elizabeth Phillips, Simon Mallal, April Frazier, Stephen A. Rawlings, Jason A. Greenbaum, Bjoern Peters, Davey M. Smith, Shane Crotty and Daniela Weiskopf.

DOI:10.1016/j.xcrm/2021/100202

About La Jolla Institute for Immunology

The La Jolla Institute for Immunology is dedicated to understanding the intricacies and power of the immune system so that we may apply that knowledge to promote human health and prevent a wide range of diseases. Since its founding in 1988 as an independent, nonprofit research organization, the Institute has made numerous advances leading toward its goal: life without disease.

INDIANAPOLIS--Researchers at the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center have identified how breast cancer cells hide from immune cells to stay alive. The discovery could lead to better immunotherapy treatment for patients.

Xinna Zhang, PhD, and colleagues found that when breast cancer cells have an increased level of a protein called MAL2 on the cell surface, the cancer cells can evade immune attacks and continue to grow. The findings are published this month in The Journal of Clinical Investigation and featured on the journal's cover.

The lead author of the study, Zhang is a member of the ...

Members of Syracuse University's College of Arts and Sciences are shining new light on an enduring mystery--one that is millions of years in the making.

A team of paleontologists led by Professor Cathryn Newton has increased scientists' understanding of whether Devonian marine faunas, whose fossils are lodged in a unit of bedrock in Central New York known as the Hamilton Group, were stable for millions of years before succumbing to waves of extinctions.

Drawing on 15 years of quantitative analysis with fellow professor Jim Brower (who died in 2018), Newton has continued to probe the structure of these ancient fossil communities, among the most renowned on Earth.

The group's findings, reported by the Geological Society of America (GSA), provide critical ...

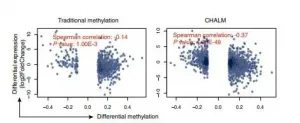

Irvine, CA - January 27, 2021 - A new University of California, Irvine-led study finds a new method for identifying biomarkers may aid in early cancer diagnosis. The study focused on lung cancer, however the Cell Heterogeneity-Adjusted cLonal Methylation (CHALM) method has been tested on aging and Alzheimer's diseases as well and is expected to be effective for studying other diseases.

"We found the CHALM method may be a valuable tool in helping researchers to identify more reliable differentially methylated genes from sequence-based methylation data," ...

Doctors are increasingly using genetic signatures to diagnose diseases and determine the best course of care, but using DNA sequencing and other techniques to detect genomic rearrangements remains costly or limited in capabilities. However, an innovative breakthrough developed by researchers at Virginia Commonwealth University Massey Cancer Center and the VCU Department of Physics promises to diagnose DNA rearrangement mutations at a fraction of the cost with improved accuracy.

Led by VCU physicist Jason Reed, Ph.D., the team developed a technique that combines a process called digital polymerase chain reaction (dPCR) with high-speed atomic force microscopy (HSAFM) to create an image with such nanoscale resolution that users can measure differences in ...

Historically redlined neighborhoods are more likely to have a paucity of greenspace today compared to other neighborhoods. The study by researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health and the University of California, Berkeley and San Francisco, demonstrates the lasting effects of redlining, a racist mortgage appraisal practice of the 1930s that established and exacerbated racial residential segregation in the United States. Results appear in Environmental Health Perspectives.

In the 1930s, the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) assigned risk grades to neighborhoods across the country based on racial demographics and other factors. "Hazardous" areas--often those whose residents included people ...

LAWRENCE -- For at least a century, ecologists have wondered at the tendency for populations of different species to cycle up and down in steady, rhythmic patterns.

"These cycles can be really exaggerated -- really huge booms and huge busts -- and quite regular," said Daniel Reuman, professor of ecology & evolutionary biology at the University of Kansas and senior scientist at the Kansas Biological Survey. "It attracted people's attention because it was kind of mysterious. Why would such a big thing be happening?"

A second observation in animal populations ...

(Boston)--Researchers from Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM) have identified proteins that are essential for the viability of whole genome doubled tumor cells, yet non-essential to normal cells that comprise the majority of human tissue.

"Exploiting these vulnerabilities represents a highly significant and currently untapped opportunity for therapeutic intervention, particularly because whole genome doubling is a distinguishing characteristic of many tumor types," said corresponding author Neil J. Ganem, PhD, associate professor of pharmacology and medicine, section of hematology and medical oncology, at Boston University School of Medicine (BUSM).

The vast majority of human cells are diploid, meaning that they possess two copies of each ...

The Asia Pacific Consortium on Osteoporosis (APCO) has today launched the first pan-Asia Pacific clinical practice standards for the screening, diagnosis, and management of osteoporosis, targeting a broad range of high-risk groups.

Published in Osteoporosis International today, 'The APCO Framework' comprises 16 minimum clinical standards set to serve as a benchmark for the provision of optimal osteoporosis care in the region.

Developed by APCO members representing key osteoporosis stakeholders, and multiple medical and surgical specialities, this set of clear, concise, relevant and pragmatic clinical standards aims to support national societies, guidelines development authorities, and health care policy makers with ...

People who take opioid medications for chronic pain may have a hard time finding a new primary care clinic that will take them on as a patient if they need one, according to a new "secret shopper" study of hundreds of clinics in states across the country.

Stigma against long-term users of prescription opioids, likely related to the prospect of taking on a patient who might have an opioid use disorder or addiction, appears to play a role, the University of Michigan research suggests.

Simulated patients who said their doctor or other primary care provider had retired were more likely to be told they could be accepted as new patients, compared with those who said their provider had stopped prescribing opioids to them for an unknown reason.

The U-M primary care provider ...

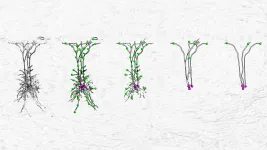

Neurons, the fundamental units of the brain, are complex computers by themselves. They receive input signals on a tree-like structure - the dendrite. This structure does more than simply collect the input signals: it integrates and compares them to find those special combinations that are important for the neurons' role in the brain. Moreover, the dendrites of neurons come in a variety of shapes and forms, indicating that distinct neurons may have separate roles in the brain.

A simple yet faithful model

In neuroscience, there has historically been a tradeoff between a model's faithfulness to the underlying biological neuron and its complexity. Neuroscientists have constructed ...