People blame a vehicle's automated system more than its driver when accidents happen

A new study looks at the public perception of blame and responsibility in semi-AV crashes

2021-02-02

(Press-News.org) Experts predict that autonomous vehicles (AVs) will eventually make our roads safer since the majority of accidents are caused by human error. However, it may be some time before people are ready to put their trust in a self-driving car.

A new study in the journal Risk Analysis found that people are more likely to blame a vehicle's automation system and its manufacturer than its human driver when a crash occurs.

Semi-autonomous vehicles (semi-AVs), which allow humans to supervise the driving and take control of the vehicle, are already on the road. For example, the 2020 Tesla Model S offers an Autopilot system, and the 2020 Cadillac CT6 has a Super Cruise system. In both, the driver must be ready to take control of the car at any moment.

However, this new study suggests that questions are likely to arise regarding blame, responsibility, and compensation when a semi-AV is involved in a collision.

Researchers led by Peng Liu, an associate professor in the College of Management and Economics at Tianjin University, conducted experiments to measure participants' responses to hypothetical semi-AV crashes. When an accident was caused by a vehicle's automated system, participants assigned more blame and responsibility to the automation and its manufacturer and indicated that the victim should be compensated more, compared to a crash caused by a human driver. They also judged the automation-caused crash to be more severe and less acceptable than one caused by a human, regardless of the seriousness of the crash (involving an injury or fatality).

Liu and his colleagues call this bias against automated systems "blame attribution asymmetry." It indicates the tendency for people to over-react to automation-caused crashes, possibly owing to the higher negative affect, or feelings and emotions, evoked by these crashes. Negative emotions such as anger can amplify attributions of legal responsibility and blame.

The authors point out that the same kind of affect-induced blame attribution asymmetry may come into play in other cooperative situations involving humans and machines. For example, surgeons working with medical robots and pilots working with military drones.

Policymakers and regulators need to be aware of people's potential over-reaction to crashes involving AVs when they set policies for deploying and regulating them, particularly with regard to financial compensation for victims injured or killed by automated systems. "According to our findings, they might need to consider the possibility that to lay people, victims of AV crashes should be compensated more than commonly calculated," the authors write.

A policy that allows what people feel are "unsafe" semi-AVs on roads could backfire as the inevitable accidents that will occur may deter more people from adopting them. To change people's negative attitudes about semi-AVs, Liu argues that "public communication campaigns are highly needed to transparently communicate accurate information, dispel public misconceptions, and provide opportunities to experience semi-AVs."

In a previous study, Liu and his colleagues conducted a field experiment where 300 participants experienced being a passenger in a semi-AV. "This direct experience led to a significant increase in trust and a reduction in negative feelings and emotions about semi-AVs," he says.

INFORMATION:

About SRA

The Society for Risk Analysis is a multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, scholarly, international society that provides an open forum for all those interested in risk analysis. SRA was established in 1980 and has published Risk Analysis: An International Journal, the leading scholarly journal in the field, continuously since 1981. For more information, visit http://www.sra.org.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-02

Recent global calamities - the pandemic, wildfires, floods - are spurring interdisciplinary scientists to nudge aside the fashionable First Law of Geography that dictates "everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things."

Geography, and by association, ecology, has largely followed what's known as Tobler's Law, which took hold in the early 1970s. But then came the novel coronavirus apparently has leapt from wildlife meat markets in China to the world in a matter of months. Global climate change creates conditions ripe for infernos in the North American west and Australia. ...

2021-02-02

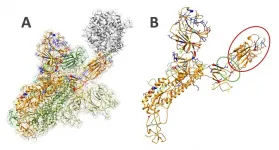

EL PASO, Texas - An effort led by Lin Li, Ph.D., assistant professor of physics at The University of Texas at El Paso, in collaboration with students and faculty from Howard University, has identified key variants that help explain the differences between the viruses that cause COVID-19 and Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS).

A team comprised of researchers from UTEP and the historically Black research university in Washington, D.C., discovered valuable data in comparing the fundamental mechanisms of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and SARS-CoV-2 -- also known as COVID-19 -- to better understand how ...

2021-02-02

CORVALLIS, Ore. - Extensive sea ice covered the world's oceans during the last ice age, which prevented oxygen from penetrating into the deep ocean waters, complicating the relationship between oxygen and carbon, a new study has found.

"The sea ice is effectively like a closed window for the ocean," said Andreas Schmittner, a climate scientist at Oregon State University and co-author on the paper. "The closed window keeps fresh air out; the sea ice acted as a barrier to keep oxygen from entering the ocean, like stale air in a room full of people. If you open the window, oxygen ...

2021-02-02

Amazon's search algorithm gives preferential treatment to books that promote false claims about vaccines, according to research by UW Information School Ph.D. student Prerna Juneja and Assistant Professor Tanu Mitra.

Meanwhile, books that debunk health misinformation appear lower in Amazon's search results, where they are less likely to be seen, the researchers wrote in a paper that was recently accepted to CHI, the top annual conference on human-computer interaction.

In their paper, Juneja and Mitra noted that Amazon has faced criticism for not regulating health-related products on its platform. They conducted audits to determine how much health misinformation is present in Amazon's recommendations ...

2021-02-02

The lockdowns and reduced societal activity related to the COVID-19 pandemic affected emissions of pollutants in ways that slightly warmed the planet for several months last year, according to new research led by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR).

The counterintuitive finding highlights the influence of airborne particles, or aerosols, that block incoming sunlight. When emissions of aerosols dropped last spring, more of the Sun's warmth reached the planet, especially in heavily industrialized nations, such as the United States and Russia, that normally pump high amounts of aerosols into the atmosphere.

"There was a big decline in emissions from the most polluting industries, and that had immediate, short-term effects on temperatures," said ...

2021-02-02

Yale researchers are developing a skin cancer treatment that involves injecting nanoparticles into the tumor, killing cancer cells with a two-pronged approach, as a potential alternative to surgery.

The results are published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"For a lot of patients, treating skin cancer is much more involved than it would be if there was a way to effectively treat them with a simple procedure like an injection," said Dr. Michael Girardi, professor and vice chair of dermatology at Yale School of Medicine and senior author of the study. "That's always been a holy grail in dermatology -- to find a simpler way to treat skin cancers such as basal cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma."

For the treatment, tumors are injected ...

2021-02-02

A new study from scientists of the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology in Plön, Germany, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Beijing shows that the potential genetic burden of mutations arising from retrogenes is significantly greater than originally thought.

Genetic information is stored in DNA and transcribed as mRNA. The mRNA is usually translated into proteins. However, it has long been known that mRNA can also be reverse transcribed to DNA and integrated back into the genome. Such cases are referred to as retrogenes. In an article, a team from the Max Planck Institute for ...

2021-02-02

When different groups of people come into contact, what's the key to motivating advantaged racial groups to join historically disadvantaged racial minority groups to strive for racial equality and social justice? It's a complex conundrum studied for years by social scientists like Linda Tropp, professor of social psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Her latest research, published in the International Journal of Intercultural Relations, tested and supported Tropp and colleagues' proposition that having open communication about group differences is a crucial pathway.

While greater contact between racial groups is typically associated with less ...

2021-02-02

New drivers between the ages of 15 and 25 account for nearly half of the more than one million road deaths that occur worldwide each year, according to the World Health Organization. Educational programs often use fear-based messaging and films of crash scenes to reduce risky driving behavior among young people. But does this "scary" approach work?

A new study published in the journal Risk Analysis suggests that fear-based messaging fails to reduce risky driving behavior, while fear-based Virtual Reality (VR) films depicting a violent collision may actually lead young drivers to take more chances behind the wheel.

A team of psychologists led by University of Antwerp researcher Clara Alida Cutello, PhD, conducted a study of 146 students ...

2021-02-02

Are Gut Microbes the Key to Unlocking Anxiety

A mouse study suggests the genetic contribution to anxiety is partially mediated by the gut microbiome

By Greta Lorge

The prevalence of anxiety disorders, already the most common mental illness in many countries, including the U.S., has surged during the novel coronavirus pandemic. A study led by researchers in Berkeley Lab's Biosciences Area provides evidence that taking care of our gut microbiome may help mitigate some of that anxiety.

The team used a genetically heterogeneous lineage of mice known as the Collaborative Cross (CC) to probe connections among genes, gut microbiome ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] People blame a vehicle's automated system more than its driver when accidents happen

A new study looks at the public perception of blame and responsibility in semi-AV crashes