(Press-News.org) Social interaction may help reverse food and cigarette cravings triggered by being in social isolation, a UNSW study in rats has found.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, used an animal model of drug addiction to show that a return to social interaction gives the same result as living in a rich, stimulating environment in reducing cravings for both sugar and nicotine rewards.

"This was an animal study, but we can probably all relate to the mental health benefits of being able to go for a coffee with our friends and having a chat," lead author Dr Kelly Clemens from UNSW Sydney's School of Psychology said. "Those sorts of activities can divert our attention from being at home and eating and drinking - but they can also be rewarding in and of themselves, and we come away from those interactions feeling relaxed, happy and valued in a way that means our general demeanour and mental health has improved."

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, social isolation was already increasing in Australia, with almost a quarter of Australians reporting feelings of loneliness or social isolation. The researcher said social isolation could have a significant impact on both mental and physical health. It can lead to anxiety, depression, compulsive overeating, and an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and cancer. "Social isolation in particular can both lead to increased drug taking, but can also make it harder for those wanting to cut down or quit," Dr Clemens said.

The UNSW Scientia Fellow is interested in why people relapse into drug use - in this case, nicotine - when they are socially isolated. "We know that if you're a regular smoker and you're trying to give up and then you see somebody else smoking on tv, smell cigarette smoke, or you see a packet of cigarettes, people experience very strong cravings," she said. "So we wanted to know if isolation increases the likelihood of picking up on those cues, and of initiating cravings."

Existing evidence tells us that both people and rodents who are anxious, or in a socially isolated environment, pay more attention to substance cues in their environment, she said. These cues are more likely to enter into their long-term memory. "And they can actually have a bigger influence over behaviour later on," she said.

While many studies have focused on the effect of isolation on adolescents, Dr Clemens concentrated on adult rats in this research. The researcher examined how cues linked to nicotine intake influenced cravings in adult rats in social isolation, and if the cravings could be reversed by returning the animals to group housing. They measured cravings by recording the amount of times the rat pressed a lever to turn on the cue that had been linked to nicotine. The team found that after a brief period of abstinence, the socially isolated rats were much more likely to relapse to nicotine seeking. But their cravings were reversed once they returned to group housing, highlighting the importance of social interaction in the treatment of substance abuse disorders.

"When we put the rats back with their cage mates, they weren't interested in the cue for the nicotine anymore, and they showed little evidence of relapse," Dr Clemens said. "The key finding of this particular study is the reversal of susceptibility to relapse with that return to group housing."

Dr Clemens said she was surprised that the benefit of returning to a social environment was so rapid. "The impact of social isolation took much longer to manifest, suggesting that social interaction may have a lasting protective effect against the development and relapse of addiction," she said.

The Scientia Fellow said the research demonstrated the consequences of social isolation for drug use are not permanent. "Smokers who want to quit are often provided with a pharmacological response to their addiction. They can access many medications and replacement therapies that can have variable results," she said. "Our findings suggest that something as simple as socialising with your friends could reduce those cravings and make you less likely to smoke.

This is consistent with other recent evidence that suggested people crave social interaction, and that isolation interacts with the brain's reward circuitry. "But it's important to note that this was research done in animals, and how exactly it translates to human behaviour needs to be the subject of further research."

While the study focused on nicotine, Dr Clemens found a similar result from sugar which was used as a control measure in the study. "This tells us that our results probably extend to other high fat, high sugar food and drinks. It is possible that if we did a similar study with alcohol, and other drugs of abuse, we might find a similar pattern. But we would have to test that specifically."

Dr Clemens said a follow up study could investigate if social isolation is leading to long term or transient changes in the brain that underly the behavioural changes that she observed.

INFORMATION:

MEDIA CONTACT:

Diane Nazaroff,

diane.nazaroff@unsw.edu.au or

0424 479 199.

The SARS-CoV-2, the new coronavirus behind the current pandemic, infects humans by binding its surface-exposed spike proteins to ACE2 receptors exposed on the cell membranes.

Upon a vaccination or a real infection, it takes several weeks before the immunity develops antibodies that can selectively bind to these spike proteins. Such antibody-labeled viruses are neutralized by the natural killer and T cells operated by the human immunity.

An alternative approach to train the immunity response is offered by researchers at the University of Illinois Chicago and California State University at Sacramento who have developed a novel strategy that redirects antibodies for other diseases existing in humans to the spike proteins ...

A higher diversity of flowering plants increases the breeding success of wild bees and may help compensate for the negative effects of insecticides. This is what researchers from the Universities of Göttingen and Hohenheim, as well as the Julius Kühn Institute, have found in a large-scale experimental study. The results have been published in the scientific journal Ecology Letters.

In their experiment, the researchers investigated how successfully the wild bee Osmia bicornis (red mason bee) reproduced. Red mason bees are important for both ecological and economic ...

Researchers in Costa Rica have found that some bacteria on the skin of amphibians prevent growth of the fungus responsible for what has been dubbed 'the amphibian apocalypse'.

Published in the journal Microbiology, the research identified a number of bacteria which could growth of the fungus Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis (Bd). One particularly dangerous strain of the fungus, called BdGPL-2, is responsible for mass amphibian die-offs around the world.

The fungus infects the skin of amphibians, breaking down the cells. As amphibians breathe and regulate water through their skin, infection is often deadly. It is believed that almost 700 species of amphibian are vulnerable to the ...

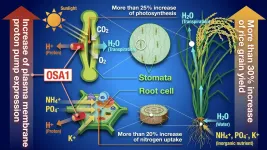

A group of scientists led by Drs Toshinori Kinoshita and Maoxing Zhang (Institute of Transformative Bio-Molecules,Nagoya University, Japan) and Dr Yiyong Zhu (Jiangsu Collaborative Innovation Center for Solid Organic Waste Utilization, Nanjing Agricultural University, China) have developed a method which, by increasing the number of a plasma membrane proton pump gene in rice, simultaneously increases nutrient uptake through the roots and stomatal opening, thus increasing the yield of paddy field grown rice by over 30%.

In their previous research, the group had found that the plasma membrane proton pump played an important role in influencing stomatal opening. When they created a variant of rice with an overexpression of a particular plasma membrane proton pump gene, they found ...

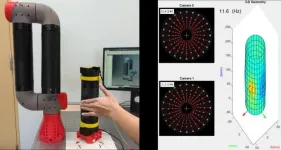

Modern-day robots are often required to interact with humans intelligently and efficiently, which can be enabled by providing them the ability to perceive touch. However, previous attempts at mimicking human skin have involved bulky and complex electronics, wiring, and a risk of damage. In a recent study, researchers from Japan sidestep these difficulties by constructing a 3D vision-guided artificial skin that enables tactile sensing with high performance, opening doors to innumerable applications in medicine, healthcare, and industry.

Robots have come a long way since their original inception for high-speed automation. Today, robots can be found in a wide variety of roles in medicine, rehabilitation, agriculture, and marine navigation. Since a ...

Modern immunotherapeutic anti-cancer drugs support a natural mechanism of the immune system to inhibit the growth of cancer cells. They dock onto a specific receptor of the killer cell and prevent it from being switched off by the cancer cells. This is a complex molecular process, which is known but has not yet been fully understood. In a molecular dynamics study conducted by the group led by medical information scientist Wolfgang Schreiner and gynaecologists Heinz Kölbl and Georg Pfeiler from MedUni Vienna, working with biosimulation expert Chris Oostenbrink ...

What are the reasons for such a contrast in outcomes? A scientist team led by the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (Leibniz-IZW) has now analysed the humoral innate immune defence of European greater mouse-eared bats to the fungus. In contrast to North American bats, European bats have sufficient baseline levels of key immune parameters and thus tolerate a certain level of infection throughout hibernation. The results are published in the journal "Developmental and Comparative Immunology".

During infections caused by Pseudogymnoascus destructans (Pd), North American bats arouse frequently from ...

To date, research in the field of combinatorial catalysts has relied on serendipitous discoveries of catalyst combinations. Now, scientists from Japan have streamlined a protocol that combines random sampling, high-throughput experimentation, and data science to identify synergistic combinations of catalysts. With this breakthrough, the researchers hope to remove the limits placed on research by relying on chance discoveries and have their new protocol used more often in catalyst informatics.

Catalysts, or their combinations, are compounds that significantly lower the energy required to drive chemical reactions to completion. In the field of "combinatorial catalyst design," the requirement of synergy--where one component ...

Life changes influence the amount of physical activity in a person, according to a recent study by the University of Jyväskylä. The birth of children and a change of residence, marital status and place of work all influence the number of steps of men and women in different ways. For women, having children, getting a job and moving from town to the countryside reduce everyday exercise.

A study conducted by the Faculty of Sports & Health Sciences found that the birth of the first child significantly reduces the number of everyday steps in women. As children grow, women's aerobic steps, in turn, increase. Although the birth of children did not have a statistically significant effect on the number of steps in men, changes were also observed ...

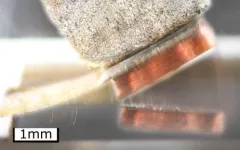

Use of waste heat contributes largely to sustainable energy supply. Scientists of Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT) and T?hoku University in Japan have now come much closer to their goal of converting waste heat into electrical power at small temperature differences. As reported in Joule, electrical power per footprint of thermomagnetic generators based on Heusler alloy films has been increased by a factor of 3.4. (DOI: 10.1016/j.joule.2020.10.019)

Many technical processes only use part of the energy consumed. The remaining fraction leaves the system ...