In an experimental exposure study, Kendra Sewall, an associate professor of biological sciences in the College of Science, and a diverse team of scientists and students have found that lead levels like those reported in Flint, Michigan, can interfere with the neural mechanisms of vocal development of songbirds and affect mate attraction.

By examining the effects of lead exposure in songbirds, more information will be known about how lead impacts learning and underlying neural networks in humans, since they share the same critical period of vocal learning.

"Our study shows that levels of lead in water that are known to be concerning for human health also have negative effects on the brain and the learning ability of male songbirds and compromises their ability to attract a mate," said Sewall, an affiliated faculty member of the Fralin Life Sciences Institute and the Global Change Center.

Their findings were published in Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety on Jan. 8.

Lead is a heavy metal. When ingested, lead competes with calcium, a nutrient that is crucial for brain growth, muscle function, and neural function. For that very reason, the Center for Disease Control and the World Health Organization consider any detectable amount of lead in blood to be dangerous for children and animal health.

One process is particularly vulnerable to lead exposure: vocal learning, a trait shared by humans and songbirds. This is because this form of learning occurs at an early age, when the brain is undergoing a significant amount of growth and reorganization.

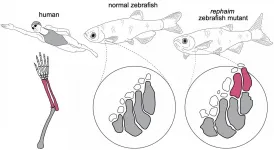

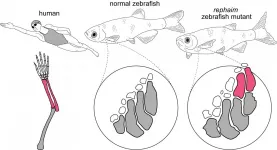

For this particular study, researchers studied male zebra finches. These small, highly social songbirds from the wilds of Australia are an excellent model for how humans learn speech. Not only do zebra finches learn their songs in the same way that we do, but they also have brain areas that are analogous to our vocal learning brain regions.

"Early in life, humans and songbirds have to hear adult vocalizations that they memorize and practice until their vocalizations are perfected," said Sewall. "If songbirds or humans are deprived of an adult model, or if their learning process is impeded by environmental challenges like lead contamination, they won't be able to produce normal vocalizations."

In order to show that this model system can be relevant to humans and our health, researchers had to determine if birds metabolize lead in the same way human children do. Sewall and her colleagues studied young male zebra finches that had been exposed to 1,000 parts per billion of lead in their drinking water, which is comparable to the highest levels that have been reported in Flint, Michigan, and measured the resulting amount of lead in their blood and brain tissue.

They found that males that had ingested the contaminated water had lead blood levels ranging from 2.6 to 6.8.

"The blood levels are concerning, but below what would trigger any major intervention if these were human blood levels," said Sewall. "Yet these blood levels adversely affected the brain and learning in these young birds. This highlights the fact that lead can be really dangerous and that we are probably ignoring levels of lead in blood and in the environment that could be causing damage to humans and animals alike."

To learn as much as they could from this study, researchers looked at additional physiological endpoints, including other aspects of learning, male coloration, and the ability of males to attract female attention.

Male songbirds who were exposed to lead produced poorer quality songs compared to the control males. Upon further inspection, researchers also found that their brains had smaller song-learning nuclei, or clusters of neurons in the central nervous system.

In addition to poor song quality, lead treated males also had differences in coloration. Male zebra finches use dances, cheek patches, and bright bills to attract females. The lead exposed males had cheek patches with less hue and red saturation than the control males.

Due to poorer song quality and dull coloration, females showed less preference for the lead-treated males, and the male's ability to attract a mate was compromised. This finding, in particular, raises the possibility that male birds exposed to environmental toxicants could have reduced reproductive success. However, it is unclear if this could have negative effects on reproduction and persistence of wild songbird populations.

Historically, research has been heavily focused on the short-term consequences of high environmental toxicant levels, rather than the long-term consequences of prolonged exposure to low levels of environmental pollutants.

"We have known for years that animals like the California condor are at risk of death from eating animals killed with lead shot," said Sewall. "Our study suggests that wild animals exposed to low levels of lead could have reduced reproduction, which is a concern for maintaining healthy wild populations. I'm reminded of a quote from Rachel Carson's 'Silent Spring,' 'but man is a part of nature, and his war against nature is inevitably a war against himself.'"

Moving forward, Sewall and the team will study the mechanism by which these low levels of lead can impair learning and indirectly impair the reproductive success of songbirds. Collaborator and Global Change Center affiliate, Chris Thompson, an assistant professor at Virginia Tech's School of Neuroscience, will be assisting with studies examining exactly how lead interferes with neural growth and causes neural damage.

"Despite knowing for many decades that lead is toxic, especially during early development, much remains unknown about the precise mechanisms by which it disrupts the brain and resulting functional outcomes such as communication," said William Hopkins, director of the Global Change Center. "The work being conducted by Sewall and her colleagues will shed light on this pervasive environmental issue that continues to have widespread adverse effects on the health and behavior of both humans and wildlife."

Sewall will also be working with Jamie Cornelius, an assistant professor at Oregon State University who is studying blood lead levels in songbirds living in parks in and around Flint, Michigan. Sewall's team will pursue more behavioral and physiological testing of wild birds at these sites.

Christopher Goodchild, an assistant professor of biology at the University of Central Oklahoma, was the first author on the paper. Michelle Beck, an assistant professor of biology at Rivier University; Sam Lane and Isaac VanDiest, who are graduate students in the Department of Biological Sciences and in the Interfaces of Global Change IGEP; and Frankie Czesak, an undergraduate Neuroscience Fellow; were all co-authors. All of their expertises and hard work were critical to the findings of this study.

"For this project, it was really critical to get all of the information that we possibly could from these birds," said Sewall. "We looked at consequences of lead exposure in water for several physiological endpoints, neurological outcomes, and learning and behavior. So, having different people who can spearhead each component of the study was really important."

INFORMATION:

Sewall is grateful to the Fralin Life Sciences Institute, the Global Change Center, and the Institute for Critical Technology and Applied Science for their continued support of her past and current work.