(Press-News.org) Under increasing global warming, tropical fish are escaping warmer seas by extending their habitat ranges towards more temperate waters.

But a new study from the University of Adelaide, published in Nature Climate Change, shows that the ocean acidification predicted under continuing high CO2 emissions may make cooler, temperate waters less welcoming.

"Every summer hundreds of tropical fish species extend their range to cooler and temperate regions as the waters of their natural habitat become a little too warm for comfort," says lead author Ericka Coni, PhD student in the University's School of Biological Sciences. "For at least two decades, Australian temperate reefs have been receiving new guests from the tropics.

"As a result of warming, we also see warm-temperate long-spined sea urchins increasing in numbers in southeast Australia, where they overgraze kelp forests and turn them into deserts known as 'urchin barrens'. Coral reef fishes that are expanding their ranges to temperate Australia prefer these barrens over the natural kelp habitats.

"But what we don't know is how expected ocean acidification, in combination with this warming, will change the temperate habitat composition and consequently the rate of tropical species range-extension into cooler water ecosystems."

The researchers hypothesised that these two divergent global change forces - warming and acidification - play opposing effects on the rate of tropicalisation of temperate waters.

"We know that as oceans warm they also acidify, because they absorb about a third of the CO2 emissions from fossil-fuel burning," says Ericka's PhD supervisor and project leader Professor Ivan Nagelkerken from the University's Environment Institute and Southern Seas Ecology Laboratories.

"We also know that calcifying species like sea urchins are typically challenged by seawater with reduced pH levels resulting from elevated CO2."

The research team, which also included Camilo Ferreira and Professor Sean Connell from the University of Adelaide, and Professor David Booth from the University of Technology Sydney, used two 'natural laboratories' to study ocean warming (tropicalisation hotspots on the south-eastern Australian coast) and ocean acidification predicted for the end of this century (natural CO2 vents off the coast of New Zealand) as an "early warning" system to assess the combined consequences of ocean acidification and ocean warming.

They found that sea urchin numbers were reduced by 87% under elevated CO2, leading to a reduction in number and size of urchin barrens. In their place turf algal cover increased which is less preferred by tropical species.

"Our study highlights that it is critical to study climate stressors together - we show that ocean acidification can mitigate some of the ecological effects of ocean warming," says Professor Nagelkerken.

"For south-eastern Australia, and likely other temperate waters, this means that ocean acidification could slow down the tropicalisation of temperate ecosystems by coral reef fishes.

"But in the meantime, if left unabated, these tropical species could increase competition with local temperate species under climate change and reduce their populations.

"In the short-term we need to take steps to preserve kelp forests to help maintain the biodiversity and populations of temperate species and reduce the invasion of tropical species."

INFORMATION:

Images:

Moorish idol - a coral reef species extending its ranges into temperate Australia under climate change.

Image credit: Ericka Coni

White Island off the coast of New Zealand, which acts as a natural laboratory to study the effects of ocean acidification on temperate reefs.

Image credit: Ericka Coni

Media Contact:

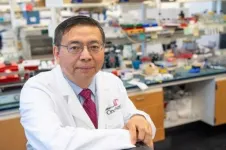

Professor Ivan Nagelkerken,

Southern Seas Ecology Laboratories and Environment Institute,

The University of Adelaide.

Mobile: +61(0)477 320 551,

ivan.nagelkerken@adelaide.edu.au

Robyn Mills,

Senior Media and Communications Officer,

University of Adelaide.

Phone: +61 (0)8 8313 6341,

Mobile: +61 (0)410 689 084,

robyn.mills@adelaide.edu.au

Recycling cans and bottles is a good practice. It helps keep the planet clean.

The same is true for recycling within cells in the body. Each cell has a way of cleaning out waste in order to regenerate newer, healthier cells. This "cell recycling" is called autophagy.

Targeting and changing this process has been linked to helping control or diminish certain cancers. Now, University of Cincinnati researchers have shown that completely halting this process in a very aggressive form of breast cancer may improve outcomes for patients one day.

These results are published in the Feb. 8 print edition of the journal Developmental Cell.

"Autophagy is sort of like cell cannibalism," ...

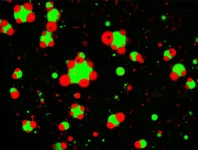

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- In cells, numerous important biochemical functions take place within spherical chambers made from proteins and RNA.

These compartments are akin to specialized rooms inside a house, but their architecture is radically different: They don't have walls. Instead, they take the form of liquid droplets that don't have a membrane, forming spontaneously, similar to oil droplets in water. Sometimes, the droplets are found alone. Other times, one droplet can be found nested inside of another. And these varying assemblies can regulate the functions the droplets perform.

A study published on Feb. 8 in Nature Communications explores how these ...

Some coronaviruses can add to their genetic pool some genes belonging to the host they infected. In this way, they can blend in and be less detectable to the immune system. This discovery was published in the journal Viruses by an Italian research team from the IIS (Italian Healthcare Institute), ISPRA (Institute for Environmental Protection and Research), IZSLER (Italian health authority and research organization for animal health and food safety of Lombardy and Emilia-Romagna) and the University of Bologna.

The outcome of this study demonstrates that coronaviruses encompass a sophisticated evolutionary mechanism ...

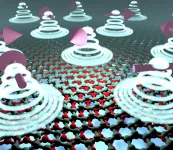

Electrons in materials have a property known as 'spin', which is responsible for a variety of properties, the most well-known of which is magnetism. Permanent magnets, like the ones used for refrigerator doors, have all the spins in their electrons aligned in the same direction. Scientists refer to this behaviour as ferromagnetism, and the research field of trying to manipulate spin as spintronics.

Down in the quantum world, spins can arrange in more exotic ways, giving rise to frustrated states and entangled magnets. Interestingly, a property similar to spin, known as "the valley," appears in graphene materials. This unique feature has given rise to the field of valleytronics, which aims to exploit the ...

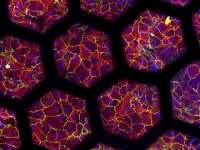

The lung is a complex organ whose main function is to exchange gases. It is the largest organ in the human body and plays a key role in the oxygenation of all the organs. Due to its structure, cellular composition and dynamic microenvironment, is difficult to mimic in vitro.

A specialized laboratory of the ARTORG Center for Biomedical Engineering Research, University of Bern, headed by Olivier Guenat has developed a new generation of in-vitro models called organs-on-chip for over 10 years, focusing on modeling the lung and its diseases. After a first successful lung-on-chip system exhibiting essential features of the lung, the Organs-on-Chip (OOC) Technologies laboratory has now developed a purely ...

Researchers have identified a new form of magnetism in so-called magnetic graphene, which could point the way toward understanding superconductivity in this unusual type of material.

The researchers, led by the University of Cambridge, were able to control the conductivity and magnetism of iron thiophosphate (FePS3), a two-dimensional material which undergoes a transition from an insulator to a metal when compressed. This class of magnetic materials offers new routes to understanding the physics of new magnetic states and superconductivity.

Using new high-pressure techniques, the researchers have shown what happens to magnetic graphene during the transition from insulator to conductor and into ...

A Rochester Institute of Technology researcher has validated a tool measuring adherence to a popular child feeding approach used by pediatricians, nutritionists, social workers and child psychologists to assess parents' feeding practices and prevent feeding problems.

The best-practice approach, known as the Satter Division of Responsibility in Feeding, has now been rigorously tested and peer reviewed, resulting in the quantifiable tool sDOR.2-6y. The questionnaire will become a standard parent survey for professionals and researchers working in the early childhood development field, predicts lead researcher ...

Astronomers may have found our galaxy's first example of an unusual kind of stellar explosion. This discovery, made with NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, adds to the understanding of how some stars shatter and seed the universe with elements critical for life on Earth.

This intriguing object, located near the center of the Milky Way, is a supernova remnant called Sagittarius A East, or Sgr A East for short. Based on Chandra data, astronomers previously classified the object as the remains of a massive star that exploded as a supernova, one of many kinds of exploded stars that scientists have catalogued.

Using longer Chandra observations, a team of astronomers has now instead concluded that the object is left over from a different type of ...

Findings from a new study on Alzheimer's disease (AD), led by researchers at the University of Saskatchewan (USask), could eventually help clinicians identify people at highest risk for developing the irreversible, progressive brain disorder and pave the way for treatments that slow or prevent its onset.

The research, published in the journal Scientific Reports in early January, has demonstrated that a shorter form of the protein peptide believed responsible for causing AD (beta-amyloid 42, or Aβ42) halts the damage-causing mechanism of ...

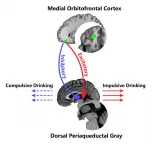

A pathway in the brain where alcohol addiction first develops has been identified by a team of British and Chinese researchers in a new study

Could lead to more effective interventions when tackling compulsive and impulsive drinking

More than 3 million deaths every year are related to alcohol use globally, according to the World Health Organisation

The physical origin of alcohol addiction has been located in a network of the human brain that regulates our response to danger, according to a team of British and Chinese researchers, co-led by the University of Warwick, the University ...