(Press-News.org) A type of cell derived from human stem cells that has been widely used for brain research and drug development may have been leading researchers astray for years, according to a study from scientists at Weill Cornell Medicine and Columbia University Irving Medical Center.

The cell, known as an induced Brain Microvascular Endothelial Cell (iBMEC), was first described by other researchers in 2012, and has been used to model the special lining of capillaries in the brain that is called the "blood-brain barrier." Many brain diseases, including brain cancers as well as degenerative and genetic disorders, could be much more treatable if researchers could get drugs across this barrier. For that and other reasons, iBMEC-based models of the barrier have been embraced as an important standard tool in brain research.

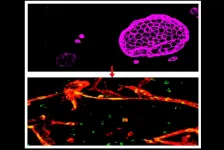

However, in a study published Feb. 4 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the Weill Cornell Medicine scientists, in collaboration with scientists at Columbia University Irving Medical Center and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, analyzed the gene expression patterns of iBMECs and found that, in fact, they are not endothelial cells--specialized cells that line blood vessels--and thus are unlikely to be useful in making accurate models of the blood-brain barrier.

"Models of key tissues and structures using stem cell technology are potentially very useful in developing better disease treatments, but as this experience indicates, we need to rigorously evaluate these models before embracing them," said co-senior author Dr. Raphaël Lis, assistant professor of reproductive medicine in medicine and a member of the Ansary Stem Cell Institute in the Division of Regenerative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine. Dr. Lis is also an assistant professor of reproductive medicine in the Ronald O. Perelman and Claudia Cohen Center for Reproductive Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Since 2007, researchers have known that they can use combinations of transcription factor proteins, which control gene activity, to reprogram ordinary adult cells, such as skin cells sampled from a patient, into cells resembling the stem cells of the embryonic stage of life. Researchers can then use similar reprogramming techniques to coax these cells, called induced pluripotent stem cells, to mature into different cell types--cells that can be studied in the lab for clues to normal health and disease.

The announcement in 2012 that researchers had made iBMECs, using such techniques, was exciting because the cells seemed to be one of the first highly tissue-specific cell types created with stem cell methods. The cells also seemed especially useful for research, for they were thought to be essentially the same as the vessel-lining endothelial cells that form the blood-brain barrier--which normally prevents most molecules in the blood from crossing into brain tissue. Research using iBMECs to model the blood-brain barrier, to better understand neurological diseases and develop new treatments, has been well funded and has expanded to involve many laboratories around the world.

In trying to work with iBMECs, the collaborating teams noted major unexplained discrepancies between these cells and bona fide endothelial cells, for example in their patterns of gene activity. That prompted them to investigate further, using advanced methods including the latest single-cell sequencing techniques, to rigorously compare the gene activity in iBMECs and in authentic human brain endothelial cells.

They found that iBMECs in fact have a largely non-endothelial pattern of gene activity, with little or no activity among key endothelial transcription factors or other accepted gene signatures. The cells, they found, also lack standard cell-surface proteins found in endothelial cells. Their analysis suggested that iBMECs were mistakenly classified as endothelial cells and rather represent different cell type called epithelial cells. Epithelial cells participate in the formation of a physical barrier shielding the body from pathogens and environmental insults, while supporting the transport of fluids, nutrients and waste. Present in numerous organs like intestines, lungs or skin, the epithelial barrier, unlike endothelial cells, is not equipped to transport blood.

The researchers noted that the initial studies of iBMECs almost a decade ago put more emphasis on the mechanical, barrier-like properties of these cells and less on their actual cellular identity as revealed through gene activity patterns.

Generation of various human tissues from pluripotent stem cells is one the most widely used techniques in laboratories world-wide. This study indicates that such techniques should be studied carefully to avoid misidentification of cells that could result in inaccurate outcomes.

"Previously there were fewer methods for studying gene expression profiles, and there was less understanding of the patterns that make up the identities of distinct cell types," said co-senior author Dr. David Redmond, assistant professor of computational biology research in medicine and a member of the Ansary Stem Cell Institute in the Division of Regenerative Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The team found that by forcing the activity of three known endothelial cell transcription factors, they could reprogram iBMECs to be much more like endothelial cells.

"We don't yet have a good 'blood-brain barrier in a lab dish' model, but I think we are now a step closer to that goal, and have also corrected an important misconception in the field," said first author Tyler Lu, a research specialist in the Ronald O. Perelman and Claudia Cohen Center for Reproductive Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

INFORMATION:

Older adults who are classified as having "prediabetes" due to moderately elevated measures of blood sugar usually don't go on to develop full-blown diabetes, according to a study led by researchers at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Doctors still consider prediabetes a useful indicator of future diabetes risk in young and middle-aged adults. However, the study, which followed nearly 3,500 older adults, of median age 76, for about six and a half years, suggests that prediabetes is not a useful marker of diabetes risk in people of more advanced age.

The results were published February 8 in JAMA ...

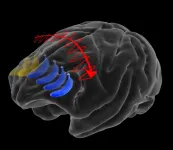

Ask anyone from an NFL quarterback scanning the field for open receivers, to an air traffic controller monitoring the positions of planes, to a mom watching her kids run around at the park: We depend on our brain to hold what we see in mind, even as we shift our gaze around and even temporarily look away. This capability of "visual working memory" feels effortless, but a new MIT study shows that the brain works hard to keep up. Whenever a key object shifts across our field of view--either because it moved or our eyes did--the brain immediately transfers a memory of it by re-encoding it among neurons in the opposite brain hemisphere.

The finding, published in Neuron by neuroscientists at The Picower Institute for Learning and Memory, explains via experiments in animals how we can keep ...

The snapping claws of male amphipods--tiny, shrimplike crustaceans--are among the fastest and most energetic of any life on Earth. Researchers reporting in the journal Current Biology on February 8 find that the crustaceans can repeatedly close their claws in less than 0.01% of a second, generating high-energy water jets and audible pops. The snapping claws are so fast, they almost defy the laws of physics.

"What's really amazing about these amphipods is that they're sitting right on the boundary of what we think is possible in terms of how small something can be and how fast it can move without self-destructing," says senior author Sheila Patek, a Professor of Biology at Duke University. "If they accelerated any faster, their bodies would break."

While amphipods are ...

What The Study Did: The National Health Service in Italy provides universal coverage to citizens but because no approved drug was available for COVID-19, patients received potentially effective drugs, participated in clinical trials, accessed compassionate drug use programs or self-medicated. This study evaluated changes in drug demand during the early phase of the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy compared with the period before the outbreak.

Authors: Adriana Ammassari, M.D., of the Italian Medicines Agency in Rome, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.37060)

Editor's ...

Philadelphia, February 8, 2021--Adding to a growing body of research affirming the benefits of fetal surgery for spina bifida, new findings show prenatal repair of the spinal column confers physical gains that extend into childhood. The researchers found that children who had undergone fetal surgery for myelomeningocele, the most severe form of spina bifida, were more likely than those who received postnatal repair to walk independently, go up and down stairs, and perform self-care tasks like using a fork, washing hands and brushing teeth. They also had stronger leg muscles and walked faster than children who had their spina bifida surgery ...

What The Study Did: This observational study compared different measures of prediabetes and the risk of progression to diabetes among adults age 71 to 90.

Authors: Mary R. Rooney, Ph.D., M.P.H., of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.8774)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflicts of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for additional information, including other authors, author contributions and ...

What The Study Did: Researchers assessed what percentage of the Virginia population had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 after the first wave of COVID-19 infections in the U.S.

Authors: Eric R. Houpt, M.D., of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.35234)

Editor's Note: The article includes conflict of interest and funding/support disclosures. Please see the article for ...

If temperature varies strongly from day to day, the economy grows less. Through these seemingly small variations climate change may have strong effects on economic growth. This shows data analyzed by researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Columbia University and the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change (MCC). In a new study in Nature Climate Change, they juxtapose observed daily temperature changes with economic data from more than 1,500 regions worldwide over 40 years - with startling results.

"We ...

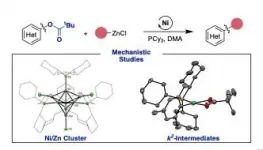

Negishi cross-coupling reactions have been widely used to form C-C bonds since the 1970s and are often perceived as the result of two metals (i.e zinc and palladium/nickel) working in synergy. But like all relationships, there is more under the surface than what we first expected. PhD student Craig Day and Dr. Rosie Somerville from the Martin group at ICIQ have delved into the Negishi cross-coupling of aryl esters using nickel catalysis to understand how this reaction works at the molecular level and how to improve it. The results have been published in Nature Catalysis.

Compared to palladium, nickel has the advantage of being readily available transition metal, ...

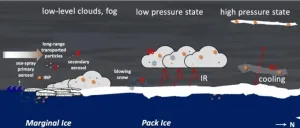

It's clear that rising greenhouse gas emissions are the main driver of global warming. But on a regional level, several other factors are at play. That's especially true in the Arctic - a massive oceanic region around the North Pole which is warming two to three times faster than the rest of the planet. One consequence of the melting of the Arctic ice cap is a reduction in albedo, which is the capacity of surfaces to reflect a certain amount of solar radiation. Earth's bright surfaces like glaciers, snow and clouds have a high reflectivity. As snow and ice decrease, albedo decreases and more radiation is absorbed by the Earth, leading to a rise in ...