Ebola is a master of disguise

Faculty of Medicine team from University of Ottawa have discovered a druggable pathway the virus uses to trick its way into our organs

2021-02-11

(Press-News.org) It was once thought that Ebola and related filoviruses were more or less contained to Central Africa. After a West African outbreak and the discovery of Reston ebolavirus in the Philippines, cuevavirus in Spain and various bat filoviruses in China, researchers now understand that this viral family--causing hemorrhagic fevers with up to 90% case fatality rates--has been widespread around the world for millions of years.

Our defenses against it are more embryonic, and though we have a vaccine against one species of Ebola and some therapeutic antibodies on the horizon, both have production or distribution issues. What doctors have been hoping for is a regular drug that can treat Ebola as soon as it rears its terrifying head. A study published today in the journal PLOS Pathogens, identifies a pathway that all filoviruses use to gain entry into our cells--and shows how they can be stopped in their tracks by at least one FDA-approved drug.

Ebola is so pernicious because it pulls a fast one on the body, disguising itself as a dying cell.

"It's cloaking itself in a lipid that is normally not exposed at the surface of a cell. It's only exposed when the cell is undergoing apoptosis," says Dr. Marceline Côté, an associate professor in the department of Biochemistry, Microbiology and Immunology, Canada Research Chair in Molecular Virology and Antiviral Therapeutics and the primary investigator on this study. Dr. Côté is a leading global expert on how viruses get into us, an understanding that is key to any effort to keep them out.

The malingering virus is then taken up by immune system cells that unwittingly carry the virus to other parts of the body, disseminating the infection. Virtually all organs become active sites of replication, and the result is a vicious, multi-system disease. Once it tricks its way into the cell, the virus needs to find a specific receptor that serves as the lock for its glycoprotein key, kicking off the process that will allow it to multiply. A drug that prevents it from any one step in turning that key could defeat the disease.

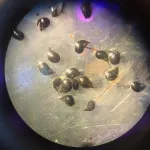

Dr. Côté's team, in particular PhD student Corina Stewart, tested a library of drugs against a virus in cell cultures. It's not safe to work with a replicating Ebola virus in a regular lab, so the uOttawa team used a surrogate system.

"We use a safe virus disguised as an Ebola virus. They will enter just the same way as an Ebola virus, but actually the inside core when they uncoat is all safe stuff," says Dr. Coté. "It's murine leukemia virus or engineered retroviruses, so nothing to worry about."

Once they found a collection of drugs that seemed to work, they passed the data to collaborator Dr. Darwyn Kobasa at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg, where a biosafety level 4 rating allows researchers to handle the bona fide virus. Dr. Kobasa confirmed that a small number of cancer chemotherapy drugs were effective in preventing Ebola from gaining a foothold in the cells.

Though these types of drugs can be tough on the body, an Ebola infection carries a high risk of death. What's more, the infection doesn't last long, so any unpleasant treatment can be similarly brief.

Knowing which drugs worked against Ebola also tells the team more about how the virus gets in. In particular, this study shows that Ebola virus has evolved ways to be active in its invasion of a cell. Previously, it was thought that viral entry was left mostly up to chance, with many particles being left behind while a random few were taken up into the cell. Dr. Côté's study shows the virus has evolved to get in very efficiently, rather than just going along for the ride.

"They are not passive passengers," says Dr. Côté. "They have their hands on the steering wheel."

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-11

At a glance:

New study suggests monetary reparations for Black descendants of people enslaved in the United States could have cut SARS-CoV-2 transmission and COVID-19 rates both among Black individuals and the population at large.

Researchers modeled the impact of structural racism on viral transmission and disease impact in the state of Louisiana.

The higher burden of SARS-CoV-2 infection among Black people also amplified the virus's spread in the wider population.

Reparations could have reduced SARS-CoV-2 transmission in the overall population by as much as 68 percent.

Compared with white people, Black individuals in the United States are more likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2, more likely ...

2021-02-11

In a recent article in the Journal of Osteopathic Medicine, authors gathered previously published research to summarize current thinking on the feasibility and efficacy of using scent detection dogs to screen for the COVID-19 virus. The researchers report that sensitivity, specificity, and overall success rates reported by the canine scent detection studies are comparable or better than the standard RT-PCR and antigen testing procedures.

These findings indicate scent detection dogs can likely be used to effectively screen and identify individuals infected with the COVID-19 virus in hospitals, senior care facilities, schools, universities, ...

2021-02-11

EUGENE, Ore. -- Feb. 11, 2021 -- Researchers have mined and combined information from two databases to link pollen and key plant traits to generate confidence in the ability to reconstruct past ecosystem services.

The approach provides a new tool to that can be used to understand how plants performed different benefits useful for humans over the past 21,000 years, and how these services responded to human and climate disturbances, including droughts and fires, said Thomas Brussel, a postdoctoral researcher in the University of Oregon's Department of Geography.

The approach is detailed in a paper published online ...

2021-02-11

Palo Alto, CA-- Understanding how plants respond to stressful environmental conditions is crucial to developing effective strategies for protecting important agricultural crops from a changing climate. New research led by Carnegie's Zhiyong Wang, Shouling, Xu, and Yang Bi reveals an important process by which plants switch between amplified and dampened stress responses. Their work is published by Nature Communications.

To survive in a changing environment, plants must choose between different response strategies, which are based on both external environmental factors and internal nutritional and energy demands. For example, a plant might either delay or accelerate its lifecycle, depending on the availability of the stored ...

2021-02-11

A negative experience with food usually leaves us unable to stomach the thought of eating that particular dish again. Using sugar-loving snails as models, researchers at the University of Sussex believe these bad experiences could be causing a switch in our brains, which impacts our future eating habits.

Like many other animals, snails like sugar and usually start feeding on it as soon as it is presented to them. But through aversive training which involved tapping the snails gently on the head when sugar appeared, the snails' behaviour was altered and they refused to feed on the sugar, even when hungry.

When the team ...

2021-02-11

FRANKFURT. More than two thirds of the earth is covered by clouds. Depending on whether they float high or low, how large their water and ice content is, how thick they are or over which region of the Earth they form, it gets warmer or cooler underneath them. Due to human influence, there are most likely more cooling effects from clouds today than in pre-industrial times, but how clouds contribute to climate change is not yet well understood. Researchers currently believe that low clouds over the Arctic and Antarctic, for example, contribute to the warming of these regions by blocking the direct radiation of long-wave heat from the Earth's surface.

All ...

2021-02-11

Low-income middle-aged African-American women with high blood pressure very commonly suffer from depression and should be better screened for this serious mental health condition, according to a study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The researchers found that in a sample of over 300 low-income, African-American women, aged 40-75, with uncontrolled hypertension, nearly 60 percent screened positively for a diagnosis of depression based on a standard clinical questionnaire about depressive symptoms.

The results appeared February 10 in JAMA Psychiatry.

"Our findings suggest that low-income, middle-aged African-American women with hypertension really should be screened for depression symptoms," ...

2021-02-11

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- People who participated in a health education program that included both mental health and physical health information significantly reduced their risks of cardiovascular disease and other chronic diseases by the end of the 12-month intervention - and sustained most of those improvements six months later, researchers found.

People who participated in the integrated mental and physical health program maintained significant improvements on seven of nine health measures six months after the program's conclusion. These included, on average, a 21% ...

2021-02-11

New research shows that biodiversity is important not just at the traditional scale of short-term plot experiments--in which ecologists monitor the health of a single meadow, forest grove, or pond after manipulating its species counts--but when measured over decades and across regional landscapes as well. The findings can help guide conservation planning and enhance efforts to make human communities more sustainable.

Published in a recent issue of Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, the multi-institutional study was led by Dr. Christopher Patrick ...

2021-02-11

STEMOs (Stroke-Einsatz-Mobile) have been serving Berlin for ten years. The specialized stroke emergency response vehicles allow physicians to start treating stroke patients before they reach hospital. For the first time, a team of researchers from Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin has been able to show that the dispatch of mobile stroke units is linked to improved clinical outcomes. The researchers' findings, which show that patients for whom STEMOs were dispatched were more likely to survive without long-term disability, have been published in JAMA*.

The phrase 'time is brain' emphasizes a fundamental principle from emergency medicine, namely that after stroke, every minute counts. Without ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Ebola is a master of disguise

Faculty of Medicine team from University of Ottawa have discovered a druggable pathway the virus uses to trick its way into our organs