(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, Feb. 15, 2021 - A paper published today in Nature shows how chemicals in the areas surrounding tumors--known as the tumor microenvironment--subvert the immune system and enable cancer to evade attack. These findings suggest that an existing drug could boost cancer immunotherapy.

The study was conducted by a team of scientists at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, led by Greg Delgoffe, Ph.D., Pitt associate professor of immunology. By disrupting the effect of the tumor microenvironment on immune cells in mice, the researchers were able to shrink tumors, prolong survival and increase sensitivity to immunotherapy.

"The majority of people don't respond to immunotherapy," said Delgoffe. "The reason is that we don't really understand how the immune system is regulated within this altered tumor microenvironment."

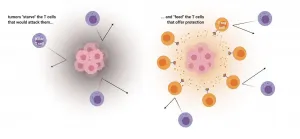

The immune system is made up of many kinds of cells, chief among them T cells. One type, called killer T cells, fights off invaders, such as viruses, bacteria and even cancer. Another type, called regulatory T cells, or "T-reg cells" for short, counteracts killer T cells by acting as protectors of the cells that belong to the body. T-reg cells are important for preventing autoimmune diseases, such as type I diabetes, Crohn's disease and multiple sclerosis, where overactive killer T cells assault the body's healthy tissues.

For all of these different immune cells to do their jobs, they need to produce energy. Delgoffe's team studied how these different types of T cells have different appetites, and how tumors--which have large appetites--compete for nutrients with infiltrating immune cells. The researchers found that killer T cells and regulatory T cells have very different appetites, and cancer cells exploit this.

"Cancer is wise to the whole situation," Delgoffe said. "Cancer cells don't just starve T cells that would kill them but actually feed these regulatory T cells that would protect them."

In short, Delgoffe's team found that tumors gobble up all the vital nutrients in their vicinity that killer T cells would need to attack. Further, they also excrete lactic acid, which feeds the regulatory T cells, convincing them to stand guard. T-regs can turn the lactic acid into energy, using a protein called MCT1, so nuzzling up with the tumor is a good way for these immune cells to stay fed.

"What better way to recruit a cell than food?" Delgoffe said.

Then, using mice with melanoma, the researchers found that silencing the gene that codes for the MCT1 protein caused tumor growth to slow down. The mice also lived longer.

"We starved the T-regs," said Delgoffe. "When T-reg cells are not being sustained by the tumor, killer T cells can come in and kill the cancer."

Importantly, when Delgoffe's team combined MCT1 inhibition with immunotherapy, the anti-cancer effects were stronger than either strategy alone.

Clinically, the same effect might be achievable using drugs that inhibit MCT1--one of which is currently being tested in people with advanced lymphoma, and it appears to be well-tolerated.

INFORMATION:

Additional authors on the study include McLane Watson, Paolo Vignali, Steven Mullett, Abigail Overacre-Delgoffe, Ph.D., Ronal Peralta, Stephanie Grebinoski, Ashley Menk, Natalie Rittenhouse, Kristin DePeaux, Ryan Whetstone, Ph.D., Dario Vignali, Ph.D., Timothy Hand, Ph.D., Amanda Poholek, Ph.D., and Stacy Wendell, Ph.D., of Pitt and UPMC; and Brett Morrison, M.D., Ph.D., and Jeffrey Rothstein, M.D., Ph.D., of Johns Hopkins University.

Funding for this study was provided by the Sidney Kimmel Foundation, National Institutes of Health (DP2AI136598, P50CA121973, P50CA097190 R01DK089125, R01CA203689, P01AI108545, T32CA082084, F31AI149971, F30CA247034, F31CA247129, T32AI089443 and F31AI147638), the American Association for Cancer Research (SU2CAACR-IRG-04-16), the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy, the Mark Foundation for Cancer Research, Cancer Research Institute, the Sy Holzer Endowed Immunotherapy Fund and the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation.

Additional Contact:

Cyndy Patton

Mobile: 412-415-6085

E-mail: PattonC4@upmc.edu

About UPMC Hillman Cancer Center

UPMC Hillman Cancer Center, ranked 7th by U.S. News & World Report in 2019 for excellence in cancer care, is the region's only National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center and is one of the largest integrated community cancer networks in the United States. Backed by the collective strength of UPMC and the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, UPMC Hillman Cancer Center has nearly 70 locations throughout Pennsylvania and Ohio with cancer centers and partnerships internationally. The more than 2,000 physicians, researchers and staff are leaders in molecular and cellular cancer biology, cancer immunology, cancer virology, biobehavioral oncology, and cancer epidemiology, prevention, and therapeutics. UPMC Hillman Cancer Center is transforming cancer research, care, and prevention -- one patient at a time.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

To read this release online or share it, visit https://www.upmc.com/media/news/021521-Delgoffe-NATURE [when embargo lifts].

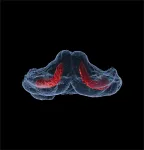

Researchers have found a way to use light and a single electron to communicate with a cloud of quantum bits and sense their behaviour, making it possible to detect a single quantum bit in a dense cloud.

The researchers, from the University of Cambridge, were able to inject a 'needle' of highly fragile quantum information in a 'haystack' of 100,000 nuclei. Using lasers to control an electron, the researchers could then use that electron to control the behaviour of the haystack, making it easier to find the needle. They were able to detect the 'needle' with a precision of 1.9 parts per million: high enough to detect a single quantum bit in this large ensemble.

The technique makes it possible to send highly fragile ...

[Images and video available: see notes to editors]

Wasps provide crucial support to their extended families by babysitting at neighbouring nests, according to new research by a team of biologists from the universities of Bristol, Exeter and UCL published today [15 February] in Nature Ecology and Evolution.

The findings suggest that animals should often seek to help more distant relatives if their closest kin are less in need.

Dr Patrick Kennedy, lead author and Marie Curie research fellow in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Bristol, said: "These wasps can act like rich family members lending a hand to their second cousins. If there's not much more you can do to help your immediate family, you can ...

Feathers are a sleek, intricate evolutionary innovation that makes flight possible for birds, but in addition to their stiff, aerodynamic feathers used for flight, birds also keep a layer of soft, fluffy down feathers between their bodies and their outermost feathers to regulate body temperature.

Using the Smithsonian's collection of 625,000 bird specimens, Sahas Barve, a Peter Buck Fellow at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History, led a new study to examine feathers across 249 species of Himalayan songbirds, finding that birds living at higher elevations have more of the fluffy down--the type of feathers humans stuff their jackets with--than birds from lower elevations. Published ...

Ciliopathies are genetic disorders caused by defects in the structure and function of cilia, microtubule-based organelles present on the surface of almost every cell in the human body which play crucial roles in cell signalling. Ciliopathies present a wide range of often severe clinical symptoms, frequently affecting the head and face and leading to conditions such as cleft palate and micrognathia (an underdeveloped lower jaw that can impair feeding and breathing). While we understand many of the genetic causes of human ciliopathies, they are only half the story: the question remains as to why, at a cellular level, defective cilia cause developmental craniofacial abnormalities. Researchers have now discovered that ciliopathic micrognathia in an animal model results from abnormal skeletal ...

Years of suffering and billions of euro in global health care costs, arising from osteoporosis-related bone fractures, could be eliminated using big data to target vulnerable patients, according to researchers at Lero, the Science Foundation Ireland Research Centre for Software.

A study of 36,590 patients who underwent bone mineral density scans in the West of Ireland between January 2000 and November 2018, found that many fractures are potentially preventable by identifying those at greatest risk before they fracture, and initiating proven, safe, low-cost effective interventions.

The multi-disciplinary study, ...

Long held in a private collection, the newly analysed tooth of an approximately 9-year-old Neanderthal child marks the hominin's southernmost known range. Analysis of the associated archaeological assemblage suggests Neanderthals used Nubian Levallois technology, previously thought to be restricted to Homo sapiens.

With a high concentration of cave sites harbouring evidence of past populations and their behaviour, the Levant is a major centre for human origins research. For over a century, archaeological excavations in the Levant have produced human ...

A recent study finds that the invasive spotted wing drosophila (Drosophila suzukii) prefers to lay its eggs in places that no other spotted wing flies have visited. The finding raises questions about how the flies can tell whether a piece of fruit is virgin territory - and what that might mean for pest control.

D. suzukii is a fruit fly that is native to east Asia, but has spread rapidly across North America, South America, Africa and Europe over the past 10-15 years. The pest species prefers to lay its eggs in ripe fruit, which poses problems for fruit growers, since consumers don't want to buy infested fruit.

To avoid consumer rejection, there are extensive measures in place to avoid infestation, and to prevent infested ...

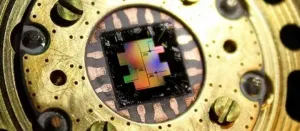

Aalto researchers have used an IBM quantum computer to explore an overlooked area of physics, and have challenged 100 year old cherished notions about information at the quantum level.

The rules of quantum physics - which govern how very small things behave - use mathematical operators called Hermitian Hamiltonians. Hermitian operators have underpinned quantum physics for nearly 100 years but recently, theorists have realized that it is possible to extend its fundamental equations to making use of Hermitian operators that are not Hermitian. The new equations describe a universe with its own peculiar set of rules: for example, by looking in the ...

It was tens of miles wide and forever changed history when it crashed into Earth about 66 million years ago.

The Chicxulub impactor, as it's known, left behind a crater off the coast of Mexico that spans 93 miles and goes 12 miles deep. Its devastating impact brought the reign of the dinosaurs to an abrupt and calamitous end by triggering their sudden mass extinction, along with the end of almost three-quarters of the plant and animal species then living on Earth.

The enduring puzzle has always been where the asteroid or comet that set off the destruction originated, and how it came to strike the Earth. And ...

The UK's commercial fishing industry is currently experiencing a number of serious challenges.

However, a study by the University of Plymouth has found that managing the density of crab and lobster pots at an optimum level increases the quality of catch, benefits the marine environment and makes the industry more sustainable in the long term.

Published today in Scientific Reports, a journal published by the Nature group, the findings are the result of an extensive and unprecedented four-year field study conducted in partnership with local fishermen off the coast of southern England.

Over a sustained period, researchers exposed sections of the seabed to differing densities of pot fishing and monitored any impacts using a combination of underwater videos and catch ...