(Press-News.org) Multi-ethnic neighborhoods in England retain their diversity and are much more stable than such neighborhoods in the U.S., according to geographers from the U.S. and U.K. The team examined how neighborhood diversity has changed on a national scale from 1991 to 2011 using U.K. Census data.

Past studies of this kind have often focused on neighborhoods in which the presence of two or three different ethnic groups constituted a diverse neighborhood but this study applied a more rigorous standard. A multi-ethnic neighborhood had to have at least five or more ethnic groups represented and no group could represent more than 45% of the neighborhood's population.

The analysis was a research collaboration by: Richard Wright, a professor of geography and the Orvil E. Dryfoos Chair of Public Affairs at Dartmouth College; Gemma Catney, a senior lecturer in geography at the School of Natural and Built Environment at Queen's University Belfast; and Mark Ellis, a professor of geography at the University of Washington.

Published recently in the Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, the study classified all English neighborhoods by ethnic mix. As 85.4% of the population identified as white in 2011, not surprisingly, the most common types were ones with a white majority. The overall share of these types of neighborhoods, however, is declining as the proportion of more diverse neighborhoods increases. The research revealed that England's multi-ethnic neighborhoods have grown steadily from 0.5% of all neighborhoods in 1991 (170 of all neighborhoods) to just over 1.5% in 2001 (528 of all neighborhoods) to over 4% in 2011 (1,417 of 32,944 neighborhoods). This may seem like a small proportion of the total, but multi-ethnic neighborhoods in England are now the third most common type. The 2011 data also indicates that about 5% percent of the total population in England or 2.5 million people lived in multi-ethnic neighborhoods.

The findings demonstrate that England's multi-ethnic neighborhoods are highly stable and are continuing to increase: 88% of multi-ethnic neighborhoods in 1991 retained their diversity in 2001, and over 95% of multi-ethnic neighborhoods in 2001 remained highly diverse in 2011. London's neighborhood diversity was the most stable in the country, accounting for 56% of multi-ethnic neighborhood stability in 1991 and 73% in 2011.

The authors asked if this stability is to be explained by high rates of owner occupancy with fewer renters or perhaps, by an aging population. The data revealed the opposite. Only 42% of the population in highly diverse neighborhoods owned their homes as compared to 67% of residents in other types of neighborhoods. When the age profiles of multi-ethnic neighborhoods were compared with other neighborhood types, the results showed a higher proportion of 20- to 30-year-olds across both white British and ethnic minority groups, reflecting recent in-migration and immigration. Given the youthful population mix, older whites aging out of these multi-ethnic neighborhoods did not appear to play a role in the stability of neighborhood diversity.

"In England, we suspect people are seeking multi-ethnic diverse neighborhoods out because they are so diverse," explains Wright. "These places may be stable because they are desirable. The typical population churn of people moving in and out may actually be contributing to this stability."

While multi-ethnic neighborhoods in England tend to be highly stable, racially diverse neighborhoods in the U.S. are not. Such U.S. neighborhoods are often transitionary, typically in the midst of a shift from being predominantly white to predominantly Latino areas. The co-authors cite their previous research, which found that "less than 50% of neighborhoods retained their high-diversity status for more than a decade (2000-2010)." One striking aspect of the recent study is that the U.K. Census relies on units (lower layer super output areas), which are much smaller in population (about 1,600 people) than the U.S. Census tracts (4,000). As the co-authors explain, while one might be inclined to think that smaller neighborhoods may be more susceptible to instability, the results prove otherwise.

The research illustrates that many of England's neighborhoods are becoming increasingly diverse and also debunks the common misconception in England that neighborhoods with ethnic populations are becoming more segregated. Greater intermixing of neighborhoods can help foster tolerance and may help reduce discrimination; however, the researchers point out that Brexit has created uncertainties with the future of immigration and emigration, which will no doubt, impact future stability of neighborhood diversity in England.

INFORMATION:

Wright is available for comment at: richard.a.wright@dartmouth.edu.

The cocktail of beneficial bacteria passed from mother to infant through breast milk changes significantly over time and could act like a daily booster shot for infant immunity and metabolism. The research, conducted by scientists from Montreal and Guatemala and published in Frontiers in Microbiology, has important implications for infant development and health.

Researchers discovered a range of microbiome species never before identified in human milk. Until now, relatively little was known about the role microbiome bacteria play in breast milk. These bacteria are thought to protect the infant gastrointestinal tract and improve aspects of long-term health, such as allergy ...

A toxin produced by bacteria as a defence mechanism causes mutations in target bacteria that could help them survive, according to a study published today in eLife.

The finding suggests that competitive encounters between bacterial cells could have profound consequences on the evolution of bacterial populations.

When bacterial cells come into contact, they often produce toxins as a defence mechanism. Although it is known that the bacteria producing these toxins have a competitive advantage, exactly how the toxins affect the recipient cells is less clear.

"Undergoing intoxication is not always detrimental for cells - there are scenarios in which encountering a toxin could provide a benefit, such as generating antibiotic ...

To combat climate change, shifting from fossil fuels to clean and sustainable energy sources is imperative. A popular candidate in this regard is hydrogen, an eco-friendly fuel that produces only water when used. However, the efficient methods of hydrogen production are usually not eco-friendly. The eco-friendly alternative of splitting water with sunlight to produce hydrogen is inefficient and suffers from low stability of the photocatalyst (material that facilitates chemical reactions by absorbing light). How does one address the issue of developing a stable and efficient photocatalyst?

In a study recently published in Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, ...

Having a memory of past events enables us to take smarter decisions about the future. Researchers at the Max-Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization (MPI-DS) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now identified how the slime mold Physarum polycephalum saves memories - although it has no nervous system.

The ability to store and recover information gives an organism a clear advantage when searching for food or avoiding harmful environments. Traditionally it has been attributed to organisms that have a nervous system.

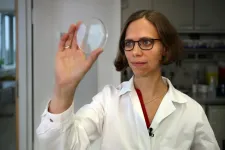

A new study authored by Mirna Kramar (MPI-DS) and Prof. Karen Alim (TUM and MPI-DS) challenges this view by uncovering the surprising abilities of a highly dynamic, single-celled organism to store and ...

During ice ages, the global mean sea level falls because large amounts sea water are stored in the form of huge continental glaciers. Until now, mathematical models of the last ice age could not reconcile the height of the sea level and the thickness of the glacier masses: the so-called Missing Ice Problem. With new calculations that take into account crustal, gravitational and rotational perturbation of the solid Earth, an international team of climate researchers has succeeded in resolving the discrepancy, among them Dr. Paolo Stocchi from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). The study, now published in the ...

During this unique study, a team of researchers led by Professor Jane Ogden from the University of Surrey investigated the impact of actively preparing or watching others prepare food (e.g., on a cooking show) versus distraction away from this focus. Researchers sought to understand how this may affect the amount of food consumed and influence the desire to continue eating.

To investigate this further, eighty female participants were recruited and assigned to one of four groups: active food preparation (preparing a cheese wrap within 10 minutes), video food preparation (watching a video of a researcher preparing a cheese wrap), distraction ...

University of Alberta researchers have found that limiting the amount of fat the body releases into the bloodstream from fat cells during heart failure could help improve outcomes for patients.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology, Jason Dyck, professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the U of A's Cardiovascular Research Centre, found that mice with heart failure that were treated with a drug blocking the release of fat into the bloodstream from fat cells saw less inflammation in the heart and throughout the body, and had better outcomes than a control group.

"Many people believe that, by definition, heart failure is only ...

New Orleans, LA - An LSU Health New Orleans School of Public Health study reports a positive association between social vulnerability and COVID-19 incidence at the census tract level and recommends that more resources be allocated to socially vulnerable populations to reduce the incidence of COVID-19. The findings are published in Frontiers in Public Health, available END ...

Gay men are more likely than lesbian women to face stigma and avoidant prejudice from their heterosexual peers due to the sound of their voice, a new study in the British Journal of Social Psychology reports. Researchers also found that gay men who believe they sound gay anticipate stigma and are more vigilant regarding the reactions of others.

During this unique study researchers from the University of Surrey investigated the role of essentialist beliefs -- the view that every person has a set of attributes that provide an insight into their identity -- of heterosexual, lesbian ...

In Wonderland, Alice drank a potion to shrink herself. In nature, some animal species shrink to escape the attention of human hunters, a process that takes from decades to millennia. To begin to understand the genetics of shrinking, scientists working at the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI) in Panama successfully extracted DNA from marine shells. Their new technique will not only shed light on how animals from lizards to lemurs shrink, it will reveal many other stories hidden in shells.

"Humans are unique as predators," said Alexis Sullivan, doctoral student at Penn ...