University of Minnesota researchers develop two new rapid COVID-19 diagnostic tests

New tests can differentiate between COVID-19 variants and multiple viruses with rapid turnaround times

2021-02-23

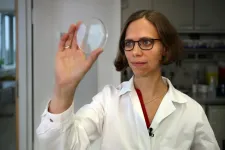

(Press-News.org) MINNEAPOLIS/ST.PAUL (02/23/2021) -- University of Minnesota Medical School researchers have developed two new rapid diagnostic tests for COVID-19 - one to detect COVID-19 variants and one to help differentiate with other illnesses that have COVID-19-like symptoms. The findings were recently published in the journal Bioengineering.

Although many people are hopeful about COVID-19 vaccines, widespread vaccine distribution isn't predicted to be available until several months from now. Until that happens, the ability to diagnose COVID-19 quickly and accurately is crucial to help minimize loss of life and continued spread of the virus.

The technology for both tests uses the cutting-edge CRISPR/Cas9 system. Using commercial reagents, they describe a Cas-9-based methodology for nucleic acid detection using lateral flow assays and fluorescence signal generation.

The first test is a rapid diagnostic test that can differentiate between COVID-19 variants. This test can be performed without specialized expertise or equipment. It uses technology similar to at-home pregnancy testing and produces results in about an hour.

The second, more sensitive test allows researchers to analyze the same sample simultaneously for COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2), Influenza A and B and respiratory syncytial virus by measuring fluorescence. These viruses manifest with similar symptoms, so being able to detect and differentiate them adds a new diagnostic tool to slow the spread of COVID-19. This test also takes about an hour and could be easily scaled so many more tests can be performed. The necessary equipment is present in most diagnostics laboratories and many research laboratories.

"The approval of the SARS-CoV-2 vaccine is highly promising, but the time between first doses and population immunity may be months," said Mark J. Osborn, PhD, assistant professor of Pediatrics at the University of Minnesota Medical School and first author of this paper. "This testing platform can help bridge the gap between immunization and immunity."

In collaboration with the U of M's Institute of Engineering in Medicine and Jakub Tolar, MD, PhD, dean of the U of M Medical School, Osborn and his team are now seeking to enhance sensitivity and real-world application of this test in support of rapidly detecting and identifying COVID-19 variants. In order to provide access to their new testing technology for healthcare providers and the public, the researchers are currently exploring ways to scale up and license their new diagnostics.

INFORMATION:

This project is supported by a U of M Medical School CO:VID (Collaborative Outcomes: Visionary Innovation & Discovery) grant and the Chambers Family Innovation Fund.

About the University of Minnesota Medical School

The University of Minnesota Medical School is at the forefront of learning and discovery, transforming medical care and educating the next generation of physicians. Our graduates and faculty produce high-impact biomedical research and advance the practice of medicine. Visit med.umn.edu to learn how the University of Minnesota is innovating all aspects of medicine.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-23

Shipping traffic can be a major source of tiny plastic particles floating in the sea, especially out in the open ocean. In a paper published in the scientific journal Environmental Science & Technology, a team of German environmental geochemists based at the University of Oldenburg's Institute of Chemistry and Biology of the Marine Environment and led by Dr Barbara Scholz-Boettcher for the first time provides an overview of microplastics mass distribution in the North Sea.

The scientists found that most of the plastic particles in water samples taken from the German Bight, an area in the south-eastern corner of the North Sea which encompasses some of the world's busiest shipping lanes, originate from binders used in marine paints. "Our hypothesis is that ships leave ...

2021-02-23

A recommendation for more intensive blood pressure management from an influential global nonprofit that publishes clinical practice guidelines in kidney disease could, if followed, benefit nearly 25 million Americans, according to an analysis led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The new recommendation from Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes, a global nonprofit that develops evidence-based clinical practice guidelines in kidney disease, is aimed at doctors to help them to reduce blood pressure for chronic kidney disease patients whose systolic blood pressure levels are over 120 mmHg. Blood pressure can be reduced using antihypertensive medications and lifestyle modifications. ...

2021-02-23

Multi-ethnic neighborhoods in England retain their diversity and are much more stable than such neighborhoods in the U.S., according to geographers from the U.S. and U.K. The team examined how neighborhood diversity has changed on a national scale from 1991 to 2011 using U.K. Census data.

Past studies of this kind have often focused on neighborhoods in which the presence of two or three different ethnic groups constituted a diverse neighborhood but this study applied a more rigorous standard. A multi-ethnic neighborhood had to have at least five or more ethnic groups represented and no group could represent more ...

2021-02-23

The cocktail of beneficial bacteria passed from mother to infant through breast milk changes significantly over time and could act like a daily booster shot for infant immunity and metabolism. The research, conducted by scientists from Montreal and Guatemala and published in Frontiers in Microbiology, has important implications for infant development and health.

Researchers discovered a range of microbiome species never before identified in human milk. Until now, relatively little was known about the role microbiome bacteria play in breast milk. These bacteria are thought to protect the infant gastrointestinal tract and improve aspects of long-term health, such as allergy ...

2021-02-23

A toxin produced by bacteria as a defence mechanism causes mutations in target bacteria that could help them survive, according to a study published today in eLife.

The finding suggests that competitive encounters between bacterial cells could have profound consequences on the evolution of bacterial populations.

When bacterial cells come into contact, they often produce toxins as a defence mechanism. Although it is known that the bacteria producing these toxins have a competitive advantage, exactly how the toxins affect the recipient cells is less clear.

"Undergoing intoxication is not always detrimental for cells - there are scenarios in which encountering a toxin could provide a benefit, such as generating antibiotic ...

2021-02-23

To combat climate change, shifting from fossil fuels to clean and sustainable energy sources is imperative. A popular candidate in this regard is hydrogen, an eco-friendly fuel that produces only water when used. However, the efficient methods of hydrogen production are usually not eco-friendly. The eco-friendly alternative of splitting water with sunlight to produce hydrogen is inefficient and suffers from low stability of the photocatalyst (material that facilitates chemical reactions by absorbing light). How does one address the issue of developing a stable and efficient photocatalyst?

In a study recently published in Applied Catalysis B: Environmental, ...

2021-02-23

Having a memory of past events enables us to take smarter decisions about the future. Researchers at the Max-Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization (MPI-DS) and the Technical University of Munich (TUM) have now identified how the slime mold Physarum polycephalum saves memories - although it has no nervous system.

The ability to store and recover information gives an organism a clear advantage when searching for food or avoiding harmful environments. Traditionally it has been attributed to organisms that have a nervous system.

A new study authored by Mirna Kramar (MPI-DS) and Prof. Karen Alim (TUM and MPI-DS) challenges this view by uncovering the surprising abilities of a highly dynamic, single-celled organism to store and ...

2021-02-23

During ice ages, the global mean sea level falls because large amounts sea water are stored in the form of huge continental glaciers. Until now, mathematical models of the last ice age could not reconcile the height of the sea level and the thickness of the glacier masses: the so-called Missing Ice Problem. With new calculations that take into account crustal, gravitational and rotational perturbation of the solid Earth, an international team of climate researchers has succeeded in resolving the discrepancy, among them Dr. Paolo Stocchi from the Royal Netherlands Institute for Sea Research (NIOZ). The study, now published in the ...

2021-02-23

During this unique study, a team of researchers led by Professor Jane Ogden from the University of Surrey investigated the impact of actively preparing or watching others prepare food (e.g., on a cooking show) versus distraction away from this focus. Researchers sought to understand how this may affect the amount of food consumed and influence the desire to continue eating.

To investigate this further, eighty female participants were recruited and assigned to one of four groups: active food preparation (preparing a cheese wrap within 10 minutes), video food preparation (watching a video of a researcher preparing a cheese wrap), distraction ...

2021-02-23

University of Alberta researchers have found that limiting the amount of fat the body releases into the bloodstream from fat cells during heart failure could help improve outcomes for patients.

In a recent study published in the American Journal of Physiology, Jason Dyck, professor of pediatrics in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry and director of the U of A's Cardiovascular Research Centre, found that mice with heart failure that were treated with a drug blocking the release of fat into the bloodstream from fat cells saw less inflammation in the heart and throughout the body, and had better outcomes than a control group.

"Many people believe that, by definition, heart failure is only ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] University of Minnesota researchers develop two new rapid COVID-19 diagnostic tests

New tests can differentiate between COVID-19 variants and multiple viruses with rapid turnaround times