(Press-News.org) As COVID-19 sweeps the world, related viruses quietly circulate among wild animals. A new study shows how SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, and SARS-CoV-1, which caused the 2003 SARS outbreak, are related to each other. The work, published recently in the journal Virus Evolution, helps scientists better understand the evolution of these viruses, how they acquired the ability to infect humans and which other viruses may be poised for human spillover.

"How did these viruses come to be what they are today? Why do some of them have the ability to infect humans while others do not?" said Simon Anthony, associate professor of pathology, microbiology and immunology in the School of Veterinary Medicine at the University of California, Davis, and senior author on the paper.

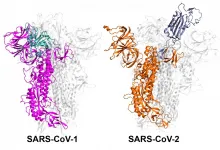

Both SARS-CoV-1 and SARS-CoV-2 belong to a group called the sarbecoviruses, Anthony said, but they are actually quite different from each other. Scientists have divided the sarbecoviruses into five lineages, with SARS-CoV-1 belonging to lineage 1 and SARS-CoV-2 to lineage 5.

Even though these two viruses belong to different lineages they both get into human cells using the ACE2 receptor.

"That is striking," Anthony said, "because there are other viruses more closely related to SARS-CoV-1 that do not use ACE2. So how did SARS-CoV-1 end up having similarities to a virus that is more distantly related?"

A family tree of viruses

Anthony and Heather Wells, a graduate student at Columbia University, constructed a family tree of all the SARS-like viruses. They found that lineage 5 -- which contains SARS-CoV-2 -- is the ancestral lineage. They concluded that most of the lineage 1 viruses related to SARS-CoV-1 lost the ability to use human ACE2 receptors long ago because of deletions in their genome. But SARS-CoV-1 and a few other viruses regained the ability to use human ACE2 at some point.

That probably occurred through a process called recombination, Wells said. For that to happen, two different viruses must have infected the same animal at the same time, producing a hybrid virus with the ability to infect humans through ACE2.

The family tree also gives insight into the geographic origins of these viruses, Wells said. So far, all ACE2-using viruses have been detected in Yunnan province, implying that SARS-CoV-2 did not originate in Wuhan, where the first cases of COVID-19 were reported, but elsewhere in China.

One unanswered question is, why did SARS-CoV-2 emerge now? If this virus has always targeted ACE2, it may long have had the ability to infect humans. So what prompted it to emerge at this time?

"There have to be other factors involved," Anthony said. "Having the genetic capacity to infect humans is only part of the story."

This study provides evolutionary context for why these viruses behave as they do, Anthony said. It allows researchers to place newly discovered viruses within the family tree and estimate whether they have the potential to infect humans.

"We now know that having the genetic potential for spillover doesn't mean it will happen -- but it is important to identify the viruses that are high risk. We can then use epidemiological or ecological studies to investigate how and if people come into contact with bats or other animals that carry these viruses," Anthony said.

"It's also a nice reminder that there are a whole lot of viruses out there that we need to understand better -- SARS-CoV-1 and 2 won't be the only ones," he said.

INFORMATION:

Additional co-authors on the study are: Tracy Goldstein, Christine Kreuder Johnson, Jonna Mazet, Michael Cranfield and Kirsten Gilardi, One Health Institute and Karen C. Drayer Wildlife Health Center, UC Davis School of Veterinary Medicine; Benard Ssebide and Julius Nziza, Gorilla Doctors and Mountain Gorilla Veterinary Project; Vincent Munster, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington; Michael Letko, and Maria Diuk-Wasser, Laboratory of Virology, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH, Hamilton, Montana; Gorka Lasso, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York; Denis Byarugaba, Makerere University, Kampala, Uganda; Isamara Navarrete-Macias and Eliza Liang, Columbia University; Barbara Han, Cary Institute of Ecosystem Studies, Millbrook, New York; and Morgan Tingley, UCLA.

The work was supported by grants from the NIH and by USAID via the PREDICT project.

WASHINGTON--Hospitalized patients with COVID-19 and abnormal sodium levels in the blood have an increased risk of experiencing respiratory failure or dying, according to a study published in the Endocrine Society's Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism.

"This study shows for the first time that patients presenting at the hospital with COVID-19 and low sodium are twice as likely to need intubation or other means of advanced breathing support as those with normal sodium," said lead investigator Ploutarchos Tzoulis, M.D., Ph.D., M.Sc., Honorary Associate Professor in Endocrinology at University College London (UCL) Medical School in London, U.K.

Additionally, the researchers found ...

An improved high-tech fluorescence microscopy technique is allowing researchers to film cells inside the breast as never seen before.

This new protocol provides detailed instructions on how to capture hi-res movies of cell movement, division and cooperation, in hard-to-reach regions of breast tissue.

The technology - called multiphoton microscopy - uses infrared lasers to illuminate fluorescently labelled breast cells without harming them, so that elusive cell behaviours can be observed within living tissue.

With the new method, WEHI researchers have revealed how breast cells rearrange, interact and sense their environment as the breast grows during development and recedes after lactation.

Cell imaging within living tissue has been ...

As the frequency and size of wildfires continues to increase worldwide, new research from Carnegie Mellon University scientists shows how the chemical aging of the particles emitted by these fires can lead to more extensive cloud formation and intense storm development in the atmosphere. The research was published online today in the journal Science Advances.

"The introduction of large amounts of ice-nucleating particles from these fires can cause substantial impacts on the microphysics of clouds, whether supercooled cloud droplets freeze or remain liquid, and the propensity of the clouds to precipitate," said Ryan Sullivan, associate ...

Caught between climate change and multi-year droughts, California communities are tapping groundwater and siphoning surface water at unsustainable rates.

As this year's below-average rainfall accentuates the problem, a public-private partnership in the Monterey/Salinas region has created a novel water recycling program that could serve as a model for parched communities everywhere.

As Stanford civil engineers report in the journal Water, this now urbanized region, still known for farming and fishing, has used water from four sources -- urban stormwater runoff, irrigation drainage, food processing water and traditional municipal wastewater ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- When healthcare workers become ill during a disease outbreak, overall case counts and mortality rates may significantly increase, according to a new model created by researchers at Penn State. The findings may help to improve interventions that aim to mitigate the effects of outbreaks such as COVID-19.

"Each year dozens of potentially lethal outbreaks affect populations around the world. For example, Ebola ravaged western Africa in 2014; Zika damaged lives in the Americas in 2015; and now we are in the midst of a worldwide pandemic -- COVID-19," said Katriona Shea, professor of biology and Alumni Professor in the Biological Sciences, Penn State. "Healthcare ...

New York, NY (February 25, 2021) -- Early detection could reduce the number of African Americans dying from liver cancer, but current screening guidelines may not find cancer soon enough in this community, according to a study published in Cancer in February.

Black patients with liver cancer often have a worse prognosis than those of other racial and ethnic groups. Mount Sinai researchers sought to understand the reasons for this disparity by studying patients with hepatitis C, the leading driver of liver cancer in the United States.

Hepatitis C virus infection can result in cirrhosis, ...

Feb. 25, 2021 - A new paper published online in the Annals of the American Thoracic Society provides a roadmap that critical care clinicians' professional societies can use to address burnout. While strongly needed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the roadmap has taken on even greater urgency due to reports of increasing pandemic-related burnout.

In "Professional Societies' Role in Addressing Member Burnout and Promoting Well-Being," Seppo T. Rinne, MD, PhD, of The Pulmonary Center, Boston University School of Medicine, and co-authors from a task force created by the Critical Care Societies Collaborative (CCSC) describe a rigorous process they used to document 17 major professional ...

The Clalit Research Institute, in collaboration with researchers from Harvard University, analyzed one of the world's largest integrated health record databases to examine the effectiveness of the Pfizer vaccine against COVID-19. The study provides the first large-scale peer-reviewed evaluation of the effectiveness of a COVID-19 vaccine in a nationwide mass-vaccination setting. The study was conducted in Israel, which currently leads the world in COVID-19 vaccination rates.

The results of this study validate and complement the previously reported findings of the Pfizer/BioNTech ...

Boston, MA - A new approach to pooled COVID-19 testing can be a highly effective tool for curbing the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, even if infections are widespread in a community, according to researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Simple pooled testing schemes could be implemented with minimal changes to current testing infrastructures in clinical and public health laboratories.

"Our research adds another tool to the testing and public health toolbox," said Michael Mina, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard Chan School and associate member of the Broad. "For public health agencies and clinical laboratories ...

ROCKVILLE, MD - Coronavirus outbreaks have occurred periodically, but none have been as devastating as the COVID-19 pandemic. Vivek Govind Kumar, a graduate student, and colleagues in the lab of Mahmoud Moradi at the University of Arkansas, have discovered one reason that likely makes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, so much more infectious than SARS-CoV-1, which caused the 2003 SARS outbreak. Moradi will present the research on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society

The first step in coronavirus infection is for the virus to enter cells. For this entry, the spike proteins on the outside of ...