Novel pooled testing strategies can significantly better identify COVID-19 infections

Strategies can also significantly improve disease spread

2021-02-25

(Press-News.org) Boston, MA - A new approach to pooled COVID-19 testing can be a highly effective tool for curbing the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, even if infections are widespread in a community, according to researchers at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. Simple pooled testing schemes could be implemented with minimal changes to current testing infrastructures in clinical and public health laboratories.

"Our research adds another tool to the testing and public health toolbox," said Michael Mina, assistant professor of epidemiology at Harvard Chan School and associate member of the Broad. "For public health agencies and clinical laboratories that are performing testing under resource limitations--which for COVID-19 is nearly every nation--this new research demonstrates that we can gain much more testing power for both medical and public health use with the same or even fewer resources than are currently being utilized."

The team's research was published online in Science Translational Medicine.

"Our work helps quantify pooled testing's tradeoffs between losses in sensitivity from sample dilution and gains in efficiency," said Brian Cleary, a Broad Fellow at the Broad and a co-corresponding author with Mina, Harvard Chan School postdoctoral research fellow James Hay, and Broad core institute member Aviv Regev (now at Genentech). "We show how to identify simple strategies that require no expertise to implement and that result in the greatest number of infections identified on a fixed budget."

By identifying infected individuals so that they can be treated or isolated, SARS-CoV-2 testing is a powerful tool for curbing the COVID-19 pandemic and safely reopening schools and businesses. But limited and sometimes costly testing throughout the pandemic has hampered diagnosing individuals and has hamstrung public health efforts to curtail the virus's spread.

Pooled testing, in which multiple individual samples are processed at once, could be a powerful tool to increase testing efficiency. If a pooled test comes back negative, all samples in that pool are considered negative, thus eliminating the need for further testing. If a pooled sample is positive, the individual samples within that testing group need to be tested again separately to identify which specific samples are positive. Although pooled testing has been implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, its usefulness is curtailed when the pathogen is widespread in a community. Under those circumstances, most pooled samples could be positive and require additional testing to identify the positive individuals in each pool. This confirmatory testing eliminates any efficiencies gained by pooled testing.

To identify ways to make pooled testing more useful during widespread outbreaks, the team developed a model for how quantities of viral RNA--which are used to identify SARS-CoV-2 infection--vary across infected people in the population during an outbreak. This gave the researchers a very detailed picture of how test sensitivity is affected by pool size and SARS-CoV-2 prevalence. They then used the model to identify optimal pooled testing strategies under different scenarios. Using the model, testing efforts could be tailored to the available resources in a community so as to maximize the number of infections identified using as few tests as possible. Even in labs with substantial resource constraints, the team created simple pooled testing schemes that could identify as many as 20 times more infected individuals per day compared with individual testing.

"Our work is a powerful study for evaluating pooled testing as a public health rather than purely clinical tool for SARS-CoV-2 and other pathogens, too," said Hay.

Harvard Chan School researcher Madikay Senghore also contributed to the study.

This research was funded by the Broad Institute, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (#U54GM088558), National Institutes of Health (1DP5OD028145-01), Wharton School, and National Science Foundation (IIS 1837992).

"Using viral load and epidemic dynamics to optimize pooled testing in resource constrained settings," Brian Cleary, James A. Hay, Brendan Blumenstiel, Maegan Harden, Michelle Cipicchio, Jon Bezney, Brooke Simonton, David Hong, Madikay Senghore, Abdul K. Sesay, Stacey Gabriel, Aviv Regev, Michael J. Mina, Science Translational Medicine, online February 23, 2021, doi: 10.1126/science.abf1568.

INFORMATION:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-25

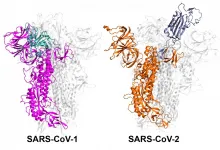

ROCKVILLE, MD - Coronavirus outbreaks have occurred periodically, but none have been as devastating as the COVID-19 pandemic. Vivek Govind Kumar, a graduate student, and colleagues in the lab of Mahmoud Moradi at the University of Arkansas, have discovered one reason that likely makes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, so much more infectious than SARS-CoV-1, which caused the 2003 SARS outbreak. Moradi will present the research on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society

The first step in coronavirus infection is for the virus to enter cells. For this entry, the spike proteins on the outside of ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - The Zika outbreak of 2015 and 2016 is having lasting impacts on children whose mothers became infected with the virus while they were pregnant. Though the numbers of Zika virus infections have dropped, which scientists speculate may be due to herd immunity in some areas, there is still potential for future outbreaks. To prevent such outbreaks, scientists want to understand how the immune system recognizes Zika virus, in hopes of developing vaccines against it. Shannon Esswein, a graduate student, and Pamela Bjorkman, a professor, at the California Institute of Technology, have new insights on how the body's antibodies attach to Zika virus. Esswein will present the work, which was published in PNAS, on Thursday, February ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - If the coronavirus were a cargo ship, it would need to deliver its contents to a dock in order to infect the host island. The first step of infection would be anchoring by the dock, and step two would be tethering to the dock to bring the ship close enough that it could set up a gangplank and unload. Most treatments and vaccines have focused on blocking the ability of the ship to anchor, but the next step is another potential target. New research by Defne Gorgun, a graduate student, and colleagues in the lab of Emad Tajkhorshid at the University of Illinois addresses the molecular details of this second step, which could inform the design of drugs that block it. Gorgun will present her research on Thursday, February 25 at the ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - The virus that causes COVID-19 belongs to the family of coronaviruses, "corona" referring to the spikes on the viral surface. These spikes are not static--to infect cells, they change shapes. Maolin Lu, an associate research scientist at Yale University, directly visualized the changing shapes of those spike proteins and monitored how the shapes change when COVID-19 patient antibodies attach. Her work, which was published in Cell Host & Microbe in December 2020 and will be presented on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society informs the development of ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - One thing that makes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, elusive to the immune system is that it is covered in sugars called glycans. Once SARS-CoV-2 infects someone's body, it becomes covered in that person's unique glycans, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize the virus as something it needs to fight. Those glycans also play an important role in activating the virus. Terra Sztain-Pedone, a graduate student, and colleagues in the labs of Rommie Amaro at the University of California, San Diego and Lillian Chong at the University of Pittsburgh, studied exactly how the glycans activate SARS-CoV-2. Sztain-Pedone will present the research on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting ...

2021-02-25

(Thursday, Feb. 25, 2021, Toronto)--Results of a world-first Canadian pilot study on patients treated with gene therapy for Fabry disease show that the treatment is working and safe.

The Canadian research team was the first to use gene therapy in 2017 to treat patients with Fabry disease, a rare, chronic illness that can damage major organs and shorten lives. They report their findings today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Being one of the first people in the world to receive this treatment, and seeing how much better I felt afterward, it definitely gives me hope that this can help many other Fabry patients and potentially those with other single gene mutation disorders," says Ryan Deveau, one of the ...

2021-02-25

Chimpanzees and humans "overlap" in their use of forests and even villages, new research shows.

Scientists used camera traps to track the movements of western chimpanzees - a critically endangered species - in Guinea-Bissau.

Chimpanzees used areas away from villages and agriculture more intensively, but entered land used by humans to get fruit - especially when wild fruits were scarce.

Researchers from the University of Exeter and Oxford Brookes University say the approach used in this study could help to inform a "coexistence strategy" for chimpanzees ...

2021-02-25

Allergy sufferers are no strangers to problems with pollen. But now - due to climate change - the pollen season is lasting longer and starting earlier than ever before, meaning more days of itchy eyes and runny noses. Warmer temperatures cause flowers to bloom earlier, while higher CO2 levels cause more pollen to be produced.

The effects of climate change on the pollen season have been studied at-length, and END ...

2021-02-25

Although guidelines do not recommend use of opioids to manage pain for individuals with knee osteoarthritis, a recent study published early online in END ...

2021-02-25

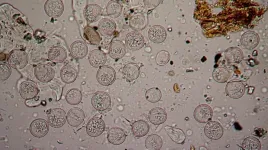

Liquid structures - liquid droplets that maintain a specific shape - are useful for a variety of applications, from food processing to cosmetics, medicine, and even petroleum extraction, but researchers have yet to tap into these exciting new materials' full potential because not much is known about how they form.

Now, a research team led by Berkeley Lab has captured real-time high-resolution videos of liquid structures taking shape as nanoparticle surfactants (NPSs) - soap-like particles just billionths of a meter in size - jam tightly together, ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Novel pooled testing strategies can significantly better identify COVID-19 infections

Strategies can also significantly improve disease spread