Scientists reveal details of antibodies that work against Zika virus

Research from the California Institute of Technology shows exactly how antibodies stick to and block the Zika virus, which will inform vaccine development

2021-02-25

(Press-News.org) ROCKVILLE, MD - The Zika outbreak of 2015 and 2016 is having lasting impacts on children whose mothers became infected with the virus while they were pregnant. Though the numbers of Zika virus infections have dropped, which scientists speculate may be due to herd immunity in some areas, there is still potential for future outbreaks. To prevent such outbreaks, scientists want to understand how the immune system recognizes Zika virus, in hopes of developing vaccines against it. Shannon Esswein, a graduate student, and Pamela Bjorkman, a professor, at the California Institute of Technology, have new insights on how the body's antibodies attach to Zika virus. Esswein will present the work, which was published in PNAS, on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Biophysical Society Annual Meeting.

Zika virus is a kind of flavivirus, and other flavivirus family members include dengue, West Nile, and yellow fever virus. To protect against these and other pathogens, "we have the ability to make a huge diversity of antibodies, and if we get infected or vaccinated, those antibodies recognize the pathogen," Esswein said. But sometimes when the body mounts an immune response against a flavivirus, there is concern that this response could make the person sicker if they get infected a second time. Called antibody-dependent enhancement (ADE), this happens when the antibodies stick to the outside of the virus without blocking its ability to infect cells, which can inadvertently help the virus infect more cells by allowing it enter cells that the antibodies stick to.

In order to prevent ADE when creating a vaccine, it's crucial for scientists to have a detailed understanding of how antibodies stick to a specific virus. This is especially important for flaviviruses, because antibodies that protect against one flavivirus may also stick to, but not protect against other flavivirus, increasing the risk of ADE. There is a concern that antibodies generated in response to a Zika virus vaccine could trigger ADE if someone were to be later infected with dengue or other flaviviruses.

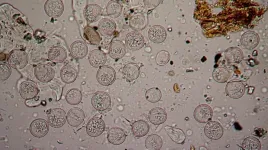

To study the antibody response to Zika and other flavivirus, Esswein and Bjorkman looked at several antibodies from the blood of patients from Mexico and Brazil. To find antibodies that recognize flaviviruses, they used a piece of the outside of the virus, called the envelope domain III protein. Previous studies have shown the envelope domain III is an important target of protective antibodies that fight flavivirus infections.

The researchers studied how those antibodies changed over time as they mature and become better able to stick to Zika virus, and also how the antibodies cross-react with other flaviviruses, including the four types of dengue viruses. They found that the Zika antibodies also tightly stick to and defend against dengue type 1, and weakly stick to West Nile and dengue types 2 and 4. "The weak cross-reactivity of these antibodies doesn't seem to defend against those flaviviruses, but also doesn't induce ADE," Esswein said, suggesting envelope domain III may be useful to make a vaccine that is safe. They also determined structures showing how two antibodies recognize Zika and West Nile envelope domain III.

Together, the team's experiments show how the body mounts "a potent immune response to Zika virus," says Esswein. Their insights into the antibodies involved in this immune response will help inform vaccine design strategy.

INFORMATION:

[Attachments] See images for this press release:

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - If the coronavirus were a cargo ship, it would need to deliver its contents to a dock in order to infect the host island. The first step of infection would be anchoring by the dock, and step two would be tethering to the dock to bring the ship close enough that it could set up a gangplank and unload. Most treatments and vaccines have focused on blocking the ability of the ship to anchor, but the next step is another potential target. New research by Defne Gorgun, a graduate student, and colleagues in the lab of Emad Tajkhorshid at the University of Illinois addresses the molecular details of this second step, which could inform the design of drugs that block it. Gorgun will present her research on Thursday, February 25 at the ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - The virus that causes COVID-19 belongs to the family of coronaviruses, "corona" referring to the spikes on the viral surface. These spikes are not static--to infect cells, they change shapes. Maolin Lu, an associate research scientist at Yale University, directly visualized the changing shapes of those spike proteins and monitored how the shapes change when COVID-19 patient antibodies attach. Her work, which was published in Cell Host & Microbe in December 2020 and will be presented on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting of the Biophysical Society informs the development of ...

2021-02-25

ROCKVILLE, MD - One thing that makes SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, elusive to the immune system is that it is covered in sugars called glycans. Once SARS-CoV-2 infects someone's body, it becomes covered in that person's unique glycans, making it difficult for the immune system to recognize the virus as something it needs to fight. Those glycans also play an important role in activating the virus. Terra Sztain-Pedone, a graduate student, and colleagues in the labs of Rommie Amaro at the University of California, San Diego and Lillian Chong at the University of Pittsburgh, studied exactly how the glycans activate SARS-CoV-2. Sztain-Pedone will present the research on Thursday, February 25 at the 65th Annual Meeting ...

2021-02-25

(Thursday, Feb. 25, 2021, Toronto)--Results of a world-first Canadian pilot study on patients treated with gene therapy for Fabry disease show that the treatment is working and safe.

The Canadian research team was the first to use gene therapy in 2017 to treat patients with Fabry disease, a rare, chronic illness that can damage major organs and shorten lives. They report their findings today in the journal Nature Communications.

"Being one of the first people in the world to receive this treatment, and seeing how much better I felt afterward, it definitely gives me hope that this can help many other Fabry patients and potentially those with other single gene mutation disorders," says Ryan Deveau, one of the ...

2021-02-25

Chimpanzees and humans "overlap" in their use of forests and even villages, new research shows.

Scientists used camera traps to track the movements of western chimpanzees - a critically endangered species - in Guinea-Bissau.

Chimpanzees used areas away from villages and agriculture more intensively, but entered land used by humans to get fruit - especially when wild fruits were scarce.

Researchers from the University of Exeter and Oxford Brookes University say the approach used in this study could help to inform a "coexistence strategy" for chimpanzees ...

2021-02-25

Allergy sufferers are no strangers to problems with pollen. But now - due to climate change - the pollen season is lasting longer and starting earlier than ever before, meaning more days of itchy eyes and runny noses. Warmer temperatures cause flowers to bloom earlier, while higher CO2 levels cause more pollen to be produced.

The effects of climate change on the pollen season have been studied at-length, and END ...

2021-02-25

Although guidelines do not recommend use of opioids to manage pain for individuals with knee osteoarthritis, a recent study published early online in END ...

2021-02-25

Liquid structures - liquid droplets that maintain a specific shape - are useful for a variety of applications, from food processing to cosmetics, medicine, and even petroleum extraction, but researchers have yet to tap into these exciting new materials' full potential because not much is known about how they form.

Now, a research team led by Berkeley Lab has captured real-time high-resolution videos of liquid structures taking shape as nanoparticle surfactants (NPSs) - soap-like particles just billionths of a meter in size - jam tightly together, ...

2021-02-25

Pheasants fall into two groups in terms of how they find their way around - and the different types prefer slightly different habitats, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists tested whether individual pheasants used landmarks (allocentric) or their own position (egocentric) to learn the way through a maze.

The captive-bred pheasants were later released into the wild, and their choice of habitat was observed.

All pheasants favoured woodland, but allocentric navigators spent more time out in the open, where their landmark-based style is more useful.

"Humans tend to use both of these navigational tactics and quite frequently combine them, ...

2021-02-25

In a major advance in the treatment of multiple myeloma, a CAR T-cell therapy has generated deep, sustained remissions in patients who had relapsed from several previous therapies, an international clinical trial has found.

In a study posted online today by the New England Journal of Medicine, trial leaders report that almost 75% of the participants responded to the therapy, known as idecabtagene vicleucel (ide-cel), and one-third of them had a complete response, or disappearance of all signs of their cancer. These rates, and the duration of the responses, are significantly ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Scientists reveal details of antibodies that work against Zika virus

Research from the California Institute of Technology shows exactly how antibodies stick to and block the Zika virus, which will inform vaccine development