(Press-News.org) States regularly use administrative records, such as motor-vehicle data, in determining whether people have moved to prune their voter rolls. A Yale-led study of this process in Wisconsin shows that a significant percentage of registered voters are incorrectly identified as having changed addresses, potentially endangering their right to vote.

The study, published in the journal Science Advances, found that at least 4% of people listed as suspected "movers" cast ballots in 2018 elections using addresses that were wrongly flagged as out of date. Minority voters were twice as likely as white voters to cast their ballot with their original address of registration after the state marked them as having moved, the study showed.

The findings suggest that states should more clearly communicate the processes they use to update voter-registration files and that a more robust effort is required to confirm whether individuals have moved before they are removed from the voter rolls, said Yale political scientist Gregory A. Huber, the study's lead author.

"The process of maintaining states' voter-registration files cries out for greater transparency," said Huber, the Forst Family Professor of Political Science in the Faculty of Arts & Sciences. "Our work shows that significant numbers of people are at risk of being disenfranchised, particularly those from minority groups.

"Unfortunately, we don't know enough about the process used to prune voter rolls nationwide to understand why mistakes occur and how to prevent them."

Regularly updating voter rolls prevents registration files from becoming bloated with individuals who have died, moved away, or are otherwise no longer eligible to vote. When these rolls swell with ineligible voters, it raises concerns about potential fraud (although there is little evidence it causes unlawful voting, Huber says) and creates headaches for political campaigns, which rely on accurate registration records to reach potential voters.

Americans are not obligated to inform local election officials when they move to a new address, but federal law mandates that states identify changes in residence among registered voters. To better accomplish this task, 30 states, including Wisconsin, and the District of Columbia have formed the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC), a non-profit organization that assists them in improving the accuracy of their voter rolls.

ERIC uses various administrative records, including motor vehicle data, change of address information from the U.S. Postal Service, and the Social Security Administration's master death file, to flag registrations that are potentially out of date. It provides states a "movers list" of people who likely have changed residences. The states contact listed individuals, often by sending them postcards they can use to confirm their address. If people do not return the postcards, their registration can be inactivated, starting the process for removal.

Federal privacy protections and ERIC's agreements with member states prohibit the organization from disclosing who is marked as having moved and on what basis they were flagged as such, making it difficult to examine its process. However, after submitting a Wisconsin Freedom of Information Act request, Huber and his co-authors obtained special "movers poll books" from the state which list all people who were marked as suspected movers and who did not respond to the postcard notification. Individuals in the books who showed up to vote in 2018 signed their names in these books, providing evidence that they voted at addresses that had been flagged as invalid.

The researchers collected movers poll books from a representative sample of election wards and matched their contents against voting records for 2018 local, state, and federal elections. They found that at least 9,000 people -- about 4% of those listed in the poll books -- voted in 2018 using the address of registration that ERIC had marked as invalid. Minority voters were twice as likely to be incorrectly identified as having moved.

The study likely undercounts the number of registered voters incorrectly listed as having moved, the researchers said, explaining that a significant number of people who did not respond to the postcard might have nonetheless renewed their voting registration before the poll books were published. In addition, the study examined low-turnout elections, making it likely that many people wrongly listed in the poll books weren't covered in the analysis because they didn't vote, Huber said.

The researchers are not suggesting that ERIC intentionally targeted minorities.

"There's no malice here," Huber said. "ERIC wants to help states, but relying on administrative records inevitably produces mistakes for any number of reasons. This makes the process used to validate having moved, such as mailed postcards, even more important. Without more information, we can't be certain why the process disparately affects minorities."

A potential reason for the disparity is that minorities are more likely than whites to live in apartment buildings and large households, which may increase the risk of errors in administrative records, the researchers suggest. In addition, residents of apartment buildings also may be less likely to confirm their address using the postcard since mail service can be spottier in multi-unit buildings than single-family homes.

Huber credits Wisconsin for taking steps to protect people's voting rights.

"The poll books are a great way to identify mistakes and prevent people from being disenfranchised," he said. "The state also has same day voter registration, which is another safety valve that doesn't exist in many states. We suggest that states expend more effort on contacting people at risk of losing their registration."

INFORMATION:

The study's co-authors are Marc Meredith of the University of Pennsylvania, Yale Law School graduate Michael Morse, and Katie Steele of the University of Pennsylvania.

The COVID-19 virus holds some mysteries. Scientists remain in the dark on aspects of how it fuses and enters the host cell; how it assembles itself; and how it buds off the host cell.

Computational modeling combined with experimental data provides insights into these behaviors. But modeling over meaningful timescales of the pandemic-causing SARS-CoV-2 virus has so far been limited to just its pieces like the spike protein, a target for the current round of vaccines.

A new multiscale coarse-grained model of the complete SARS-CoV-2 virion, its core genetic material and virion shell, has been developed for the first time using supercomputers. The model offers ...

Litter is not only a problem on Earth. According to NASA, there are currently millions of pieces of space junk in the range of altitudes from 200 to 2,000 kilometers above the Earth's surface, which is known as low Earth orbit (LEO). Most of the junk is comprised of objects created by humans, like pieces of old spacecraft or defunct satellites. This space debris can reach speeds of up to 18,000 miles per hour, posing a major danger to the 2,612 satellites that currently operate at LEO. Without effective tools for tracking space debris, parts of LEO may even become too hazardous for satellites.

In a paper publishing today in the SIAM Journal on Imaging Sciences, Matan Leibovich (New York University), George Papanicolaou (Stanford University), and Chrysoula Tsogka (University of California, ...

The unprecedented cost of the 2018 Kilauea eruption in Hawai'i reflects the intersection of distinct physical and social phenomena: infrequent, highly destructive eruptions, and atypically high population growth, according to a new study published in Nature Communications and led by University of Hawai'i at Mānoa researchers.

It has long been recognized that areas in Puna, Hawai'i, are at high risk from lava flows. This ensured that land values were lower in Puna--which lies within the three highest risk lava hazard zones 1, 2 and 3--which actively promoted rapid population ...

Our body consists of 100 trillion cells that communicate with each other, receive signals from the outside world and react to them. A central role in this communication network is attributed to receiver proteins, called receptors, which are anchored at the cell membrane. There, they receive and transmit signals to the inside of the cell, where a cell reaction is triggered.

In humans, G protein-coupled receptors (GPC receptors) represent the largest group of these receptor molecules, with around 700 different types. The research of the Frankfurt and Leipzig scientists focused on a GPC receptor that serves as a receptor for the ...

Timothy Callaghan, PhD, and Alva Ferdinand, DrPH, JD, from the Southwest Rural Health Research Center at Texas A&M University School of Public Health, joined colleagues in the first national study of how often people in urban and rural areas in the United States follow COVID-19 guidelines. These include public health best practices like wearing masks in public, sanitizing homes and work areas, maintaining physical distancing, working from home and avoiding dining in restaurants or bars.

The research team used a survey of 5,009 U.S. adults that closely matched the makeup of the country's population as a whole. The survey asked how often participants followed COVID-19 prevention recommendations and collected data on political ideology, perceived risk ...

ITHACA, N.Y. - A team from Cornell University's Environmental Systems Lab, led by recent graduate Allison Bernett, has put forth a new framework for injecting as much information as possible into the pre-design and early design phases of a project, potentially saving architects and design teams time and money down the road.

"(Our framework) allows designers to understand the full environmental impact of their building," said Bernett, corresponding author of "Sustainability Evaluation for Early Design (SEED) Framework for Energy Use, Embodied Carbon, Cost, and Daylighting Assessment" which published Jan. 10 in the Journal of ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. -- Doppler radar improves lives by peeking inside air masses to predict the weather. A Purdue University team is using similar technology to look inside living cells, introducing a method to detect pathogens and treat infections in ways that scientists never have before.

In a new study, the team used Doppler to sneak a peek inside cells and track their metabolic activity in real time, without having to wait for cultures to grow. Using this ability, the researchers can test microbes found in food, water, and other environments to see if they are pathogens, or help them identify the right medicine to treat antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

David Nolte, Purdue's Edward ...

HOUSTON - (Feb. 25, 2021) - Low-income livestock farmers in developing countries are often faced with a difficult dilemma: protect their animals from endangered predators, or spare the threatened species at the expense of their livestock and livelihood.

A new paper by Rice University economist Ted Loch-Temzelides examines such circumstances faced by farmers in Pakistan. "Conservation, risk aversion, and livestock insurance: The case of the snow leopard" outlines a plan under which farmers can protect themselves from crippling financial losses while ...

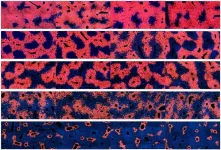

While the amazing regenerative power of the liver has been known since ancient times, the cells responsible for maintaining and replenishing the liver have remained a mystery. Now, research from the Children's Medical Center Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) has identified the cells responsible for liver maintenance and regeneration while also pinpointing where they reside in the liver.

These findings, reported today in Science, could help scientists answer important questions about liver maintenance, liver damage (such as from fatty liver or alcoholic liver disease), and liver cancer.

The liver performs vital functions, including chemical detoxification, blood protein production, bile excretion, and regulation of energy metabolism. Structurally, the liver ...

Paleo-ecologists from The University of New Mexico and at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln have demonstrated that the offspring of enormous carnivorous dinosaurs, such as Tyrannosaurus rex may have fundamentally re-shaped their communities by out-competing smaller rival species.

The study, released this week in the journal Science, is the first to examine community-scale dinosaur diversity while treating juveniles as their own ecological entity.

"Dinosaur communities were like shopping malls on a Saturday afternoon ? jam-packed with teenagers" explained Kat Schroeder, a graduate student in the UNM Department of Biology who led the study. "They made up a significant portion of the individuals in a species and would have had a very real impact ...