(Press-News.org) A large proportion of the benefit that a person gets from taking a real drug or receiving a treatment to alleviate pain is due to an individual's mindset, not to the drug itself. Understanding the neural mechanisms driving this placebo effect has been a longstanding question. A meta-analysis published in Nature Communications finds that placebo treatments to reduce pain, known as placebo analgesia, reduce pain-related activity in multiple areas of the brain.

Previous studies of this kind have relied on small-scale studies, so until now, researchers did not know if the neural mechanisms underlying placebo effects observed to date would hold up across larger samples. This study represents the first large-scale mega-analysis, which looks at individual participants' whole brain images. It enabled researchers to look at parts of the brain that they did not have sufficient resolution to look at in the past. The analysis was comprised of 20 neuroimaging studies with 600 healthy participants. The results provide new insight on the size, localization, significance and heterogeneity of placebo effects on pain-related brain activity.

The research reflects the work of an international collaborative effort by the Placebo Neuroimaging Consortium, led by Tor Wager , the Diana L. Taylor Distinguished Professor in Neuroscience at Dartmouth and Ulrike Bingel, a professor at the Center for Translational Neuro- and Behavioral Sciences in the department of neurology at University Hospital Essen, for which Matthias Zunhammer and Tamás Spisák at the University Hospital Essen, served as co-authors. The meta-analysis is the second with this sample and builds on the team's earlier research using an established pain marker developed earlier by Wager's lab.

"Our findings demonstrate that the participants who showed the most pain reduction with the placebo also showed the largest reductions in brain areas associated with pain construction," explains co-author Wager, who is also the principal investigator of the Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience Lab at Dartmouth. "We are still learning how the brain constructs pain experiences, but we know it's a mix of brain areas that process input from the body and those involved in motivation and decision-making. Placebo treatment reduced activity in areas involved in early pain signaling from the body, as well as motivational circuits not tied specifically to pain."

Across the studies in the meta-analysis, participants had indicated that they felt less pain; however, the team wanted to find out if the brain responded to the placebo in a meaningful way. Is the placebo changing the way a person constructs the experience of pain or is it changing the way a person thinks about it after the fact? Is the person really feeling less pain?

With the large sample, the researchers were able to confidently localize placebo effects to specific zones of the brain, including the thalamus and the basal ganglia. The thalamus serves as a gateway for sights and sounds and all kinds of sensory motor input. It has lots of different nuclei, which act like processing stations for different kinds of sensory input. The results showed that parts of the thalamus that are most important for pain sensation were most strongly affected by the placebo. In addition, parts of the somatosensory cortex that are integral to the early processing of painful experiences were also affected. The placebo effect also impacted the basal ganglia, which are important for motivation and connecting pain and other experiences to action. "The placebo can affect what you do with the pain and how it motivates you, which could be a larger part of what's happening here," says Wager. "It's changing the circuitry that's important for motivation."

The findings revealed that placebo treatments reduce activity in the posterior insula, which is one of the areas that are involved in early construction of the pain experience. This is the only site in the cortex that you can stimulate and invoke the sense of pain. The major ascending pain pathway goes from parts of the thalamus to the posterior insula. The results provide evidence that the placebo affects that pathway for how pain is constructed.

Prior research has illustrated that with placebo effects, the prefrontal cortex is activated in anticipation of pain. The prefrontal cortex helps keep track of the context of the pain and maintain the belief that it exists. When the prefrontal cortex is activated, there are pathways that trigger opioid release in the midbrain that can block pain and pathways that can modify pain signaling and construction.

The team found that activation of the prefrontal cortex is heterogeneous across studies, meaning that no particular areas in this region were activated consistently or strongly across the studies. These differences across studies are similar to what is found in other areas of self-regulation, where different types of thoughts and mindsets can have different effects. For example, other work in Wager's laboratory has found that rethinking pain by using imagery and storytelling typically activates the prefrontal cortex, but mindful acceptance does not. Placebo effects likely involve a mix of these types of processes, depending on the specifics of how it is given and people's predispositions.

"Our results suggest that placebo effects are not restricted solely to either sensory/nociceptive or cognitive/affective processes, but likely involves a combination of mechanisms that may differ depending on the placebo paradigm and other individual factors," explains Bingel. "The study's findings will also contribute to future research in the development of brain biomarkers that predict an individual's responsiveness to placebo and help distinguish placebo from analgesic drug responses, which is a key goal of the new collaborative research center, Treatment Expectation ."

Understanding the neural systems that utilize and moderate placebo responses has important implications for clinical care and drug-development. The placebo responses could be utilized in a context-, patient-, and disease-specific manner. The placebo effect could also be leveraged alongside a drug, surgery, or other treatment, as it could potentially enhance patient outcomes.

Wager and Bingel are available for comment.

INFORMATION:

In June 2019, an international team brought the complete skull of the 3.67-million-year-old Little Foot Australopithecus skeleton, from South Africa to the UK and achieved unprecedented imaging resolution of its bony structures and dentition in an X-ray synchrotron-based investigation at the UK's national synchrotron, Diamond Light Source. The X-ray work is highlighted in a new paper in e-Life, published today (2nd March 2021) focusing on the inner craniodental features of Little Foot. The remarkable completeness and great age of the Little Foot skeleton makes it a crucially important ...

Publishing in peer-reviewed scientific journals is crucial for the development of a researcher's career. The scientists that publish the most often in the most prestigious journals generally acquire greater renown, as well as higher responsibilities. However, a team involving two CNRS researchers* has just shown that the vast majority of scientific articles in the fields of ecology and conservation biology are authored by men working in a few Western countries. They represent 90% of the 1,051 authors that have published the most frequently in the 13 major scientific journals in the field since 1945. ...

WASHINGTON (Mar. 2, 2021) -- A report released today by the George Washington University Program on Extremism reveals new information about the 257 people charged in federal court for playing a role in the Jan. 6 attack on the United States Capitol. The report, "This is Our House!" A Preliminary Assessment of the Capitol Hill Siege Participants," also provides several recommendations aimed at combating domestic extremism.

The GW Program on Extremism tracked and categorized the people charged so far in the attack and the resulting report provides a preliminary assessment of the siege participants.

"The events of Jan. 6 may mark a watershed moment for domestic violent ...

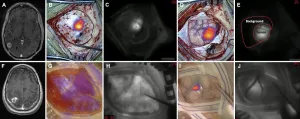

Charlottesville, VA (March 2, 2021). Researchers in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania conducted a prospective cohort study utilizing their technique of delayed near-infrared imaging with high-dose indocyanine green (called "second window ICG" or "SWIG") in the identification of brain metastases during surgery. In this study, all metastatic lesions enhanced under near-infrared light with application of SWIG. The researchers compared near-infrared SWIG images obtained at the end of tumor resection with postoperative gadolinium-enhanced MRIs, considered the gold standard for imaging. The comparison demonstrated that SWIG can be used to predict the extent of gross-total resection and, ...

Since 1970, bird populations in North America have declined by approximately 2.9 billion birds, a loss of more than one in four birds. Factors in this decline include habitat loss and ecosystem degradation from human actions on the landscape.

At the same time, enthusiasm for bird-watching has grown, with more than 45 million recreational participants in the United States alone. Now, researchers are looking into how to mobilize these bird enthusiasts to help limit bird population declines.

Enter bird-friendly coffee.

Bird-friendly coffee is certified organic, but its impact on the environment goes further than that: it is cultivated specifically to maintain bird habitats instead of clearing vegetation that birds and other animals rely on.

Researchers ...

A new paper in Oxford Open Materials Science, published by Oxford University Press, presents low cost modifications to existing N95 masks that prolongs their effectiveness and improves their reusability post disinfectants.

The COVID-19 crisis has increased demand for respiratory masks, with various models of DIY masks becoming popular alongside the commercially available N95. The utility of such masks is primarily based on the size of aerosols that they are capable of filtering out and how long they can do so effectively.

Conventional masks like the N95 use a layered system and have an efficiency ...

Researchers at Tokyo Institute of Technology working in collaboration with colleagues at the Kanagawa Institute of Industrial Science and Technology and Nara Medical University in Japan have succeeded in preparing a material called cerium molybdate (γ-Ce2Mo3O13 or CMO), which exhibits high antiviral activity against coronavirus.

The ongoing coronavirus pandemic has highlighted the urgency not only of vaccine development and rollout but also of developing innovative materials and technologies with antiviral properties that could play a vital role in helping to contain the spread of the virus.

Conventional inorganic antimicrobial materials are often prepared with metals such as copper or photocatalysts ...

Peer Reviewed

Experimental

Animals

Consumption of a high fat diet may be activating a response in the heart that is causing destructive growth and lead to greater risk of heart attacks, according to new research.

In a paper published in Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, researchers looked at the effect of feeding mice a high fat diet on oxidative stress levels on heart cells. The team from the University of Reading found that cells from the mice had twice the amount of oxidative stress, and led to heart cells being up to 1.8 times bigger due to cardiac hypertrophy which is associated with heart disease.

Named first author Dr Sunbal Naureen ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New technology from Purdue University innovators may help improve tissue restoration outcomes for people with breast cancer and other diseases or traumatic injuries.

Purdue researchers, along with fellowship-trained breast surgeon Carla Fisher of Indiana University School of Medicine, teamed up with Purdue startup GeniPhys to develop and perform preclinical studies on a regenerative tissue filler.

This is a first-of-a-kind, in situ scaffold-forming collagen. When applied as a filler for soft tissue defects and voids, it shows promise for accelerating and improving tissue restoration outcomes. The team's work is published in Scientific Reports.

"It ...

The Acheulean was estimated to have died out around 200,000 years ago but the new findings suggest it may have persisted for much longer, creating over 100,000 years of overlap with more advanced technologies produced by Neanderthals and early modern humans.

The research team, led by Dr Alastair Key (Kent) alongside Dr David Roberts (Kent) and Dr Ivan Jaric (Biology Centre of the Czech Academy of Sciences), made the discovery whilst studying stone tool records from different regions across the world. Using statistical techniques new to archaeological science, the archaeologists and conservation experts were able to reconstruct the end of the Acheulean period and re-map the archaeological record.

Previously, a more rapid shift between the earlier Acheulean stone ...