(Press-News.org) BIRMINGHAM, Ala. - Studies of the microbiome in the human gut focus mainly on bacteria. Other microbes that are also present in the gut -- viruses, protists, archaea and fungi -- have been largely overlooked.

New research in mice now points to a significant role for fungi in the intestine -- the communities of molds and yeasts known as the mycobiome -- that are the active interface between the host and their diet.

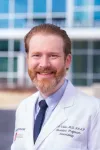

"We showed that the gut mycobiome of healthy mice was shaped by the environment, including diet, and that it significantly correlated with metabolic outcomes," said Kent Willis, M.D., an assistant professor at the University of Alabama at Birmingham and co-corresponding author of the study, published in the journal Communications Biology. "Our results support a role for the gut mycobiome in host metabolic adaptation, and these results have important implications regarding the design of microbiome studies and the reproducibility of experimental studies of host metabolism."

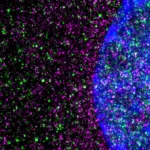

Willis and colleagues looked at fungi in the jejunum of the mouse small intestine, site of the most diverse fungal population in the mouse gut. They found that exposure to a processed diet, which is representative of a typical Western diet rich in purified carbohydrates, led to persistent differences in fungal communities that significantly associated with differential deposition of body mass in male mice, as compared to mice fed a standardized diet.

The researchers found that fat deposition in the liver, transcriptional adaptation of metabolically active tissues and serum metabolic biomarker levels were all linked with alterations in fungal

community diversity and composition. Variations of fungi from two genera -- Thermomyces and Saccharomyces -- were the most strongly associated with metabolic disturbance and weight gain.

The study had an ingenious starting point. The researchers obtained genetically identical mice from four different research animal vendors. It is known that gut bacterial communities vary markedly by vendor. Similarly, the researchers found dramatically different variability by vendor for the jejunum mycobiomes, as measured by sequencing internal transcribed spacer rRNA. At baseline, mice from one of the vendors had five unique fungal genera, and mice from the other three vendors had three, two and one unique genera, respectively.

They also looked at interkingdom community composition -- meaning bacteria as well as fungi -- and found large baseline bacterial community differences. From this initial fungal and bacterial diversity, they then measured the effects of time and differences in diet -- standardized chow versus the highly processed diet -- on fungal and bacterial community composition.

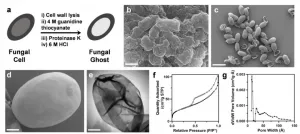

The researchers also addressed a fundamental question: Are the fungal organisms detected by next-generation sequencing coming from the diet, or are they true commensal organisms that colonize and replicate in the gut? They compared sequencing of the food pellets, which contained some fungi, and the contents of the mouse jejunum to show the jejunum fungi were true commensal colonizers.

Thus, this study, led by Willis -- and co-corresponding author Joseph Pierre, Ph.D., and co-first authors Tahliyah S. Mims and Qusai Al Abdallah, Ph.D., from the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, Tennessee -- showed that variations in the relative abundance and composition of the gut mycobiome correlate with key features of host metabolism. This lays a foundation towards understanding the complex interkingdom interactions between bacteria and fungi and how they both collectively shape, and potentially contribute to, host homeostasis.

"Our results highlight the potential importance of the gut mycobiome in health, and they have implications for human and experimental metabolic studies," Pierre said. "The implication for human microbiome studies, which often examine only bacteria and sample only fecal communities, is that the mycobiome may have unappreciated effects on microbiome-associated outcomes."

The research was mostly done at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, where Willis was an assistant professor before joining the Division of Neonatology in the UAB Department of Pediatrics last summer.

The translational research in the Willis Lung Lab at UAB seeks to understand how such commensal fungi influence newborn physiology and disease, principally via exploring the gut-lung axis in bronchopulmonary dysplasia, a lung disease of premature newborns. The study in Communications Biology using adult animals, Willis says, helped develop models for on-going research in newborn animals.

Co-authors with Willis, Pierre, Mims and Al Abdallah in the study, "The gut mycobiome of healthy mice is shaped by the environment and correlates with metabolic outcomes in response to diet," are Justin D. Stewart, Villanova University, Radnor, Pennsylvania; and Sydney P. Watts, Catrina T. White, Thomas V. Rousselle, Ankush Gosain, Amandeep Bajwa and Joan C. Han, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

INFORMATION:

Support came from National Institutes of Health grants CA253329, HL151907, DK117183 and DK125047.

JUPITER, FL -- In 1993, scientists discovered that a single mutated gene, HTT, caused Huntington's disease, raising high hopes for a quick cure. Yet today, there's still no approved treatment.

One difficulty has been a limited understanding of how the mutant huntingtin protein sets off brain cell death, says neuroscientist Srinivasa Subramaniam, PhD, of Scripps Research, Florida. In a new study published in Nature Communications on Friday, Subramaniam's group has shown that the mutated huntingtin protein slows brain cells' protein-building machines, called ribosomes.

"The ribosome has to keep moving along to build the proteins, but in Huntington's disease, the ribosome is slowed," Subramaniam says. "The difference may be two, three, four-fold ...

The body is amazing at healing itself. However, sometimes it can overdo it. Excess scarring after abdominal and pelvic surgery within the peritoneal cavity can lead to serious complications and sometimes death. The peritoneal cavity has a protective lining containing organs within our abdomen. It also contains fluid to keep the organs lubricated. When the lining gets damaged, tissue and scarring can form, creating problems. Researchers at the University of Calgary and University of Bern, Switzerland, have discovered what's causing the excess scarring and options to try to prevent it.

"This is a worldwide concern. Complications from these peritoneal adhesions cause pain and can lead to life-threatening small bowel obstruction, and infertility in women," says Dr. Joel Zindel, MD, University ...

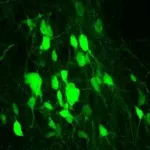

Researchers at Indiana University School of Medicine have successfully reprogrammed a glial cell type in the central nervous system into new neurons to promote recovery after spinal cord injury--revealing an untapped potential to leverage the cell for regenerative medicine.

The group of investigators published their findings March 5 in Cell Stem Cell. This is the first time scientists have reported modifying a NG2 glia--a type of supporting cell in the central nervous system--into functional neurons after spinal cord injury, said Wei Wu, PhD, research associate in neurological surgery at IU School of Medicine and co-first author of the ...

PULLMAN, Wash. - The ability to identify misinformation only benefits people who have some skepticism toward social media, according to a new study from Washington State University.

Researchers found that people with a strong trust in information found on social media sites were more likely to believe conspiracies, which falsely explain significant events as part of a secret evil plot, even if they could identify other types of misinformation. The study, published in the journal Public Understanding of Science on March 5, showed this held true for beliefs in older conspiracy theories as well as newer ones around COVID-19.

"There was some ...

Boulder, Colo., USA: In its large caldera, Newberry volcano (Oregon, USA) has two small volcanic lakes, one fed by volcanic geothermal fluids (Paulina Lake) and one by gases (East Lake). These popular fishing grounds are small windows into a large underlying reservoir of hydrothermal fluids, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) with minor mercury (Hg) and methane into East Lake.

What happens to all that CO2 after it enters the bottom waters of the lake, and how do these volcanic gases influence the lake ecosystem? Some lakes fed by volcanic CO2 have seen catastrophic ...

Research over the last decade has shown that loneliness is an important determinant of health. It is associated with considerable physical and mental health risks and increased mortality. Previous studies have also shown that wisdom could serve as a protective factor against loneliness. This inverse relationship between loneliness and wisdom may be based in different brain processes.

In a study published in the March 5, 2021 online edition of Cerebral Cortex, researchers at University of California San Diego School of Medicine found that specific regions of the brain respond to emotional stimuli related to loneliness and wisdom in opposing ways.

"We were interested ...

DURHAM, N.C. -- When you think about what separates humans from chimpanzees and other apes, you might think of our big brains, or the fact that we get around on two legs rather than four. But we have another distinguishing feature: water efficiency.

That's the take-home of a new study that, for the first time, measures precisely how much water humans lose and replace each day compared with our closest living animal relatives.

Our bodies are constantly losing water: when we sweat, go to the bathroom, even when we breathe. That water needs to be replenished to keep blood volume and other body fluids within normal ranges.

And yet, research published March 5 in the journal Current Biology shows that the human body uses 30% to 50% less water per ...

The idea of creating selectively porous materials has captured the attention of chemists for decades. Now, new research from Northwestern University shows that fungi may have been doing exactly this for millions of years.

When Nathan Gianneschi's lab set out to synthesize melanin that would mimic that which was formed by certain fungi known to inhabit unusual, hostile environments including spaceships, dishwashers and even Chernobyl, they did not initially expect the materials would prove highly porous-- a property that enables the material to store and capture molecules.

Melanin has been found across living organisms, on our skin and the backs of ...

Using genetic engineering, researchers at UT Southwestern and Indiana University have reprogrammed scar-forming cells in mouse spinal cords to create new nerve cells, spurring recovery after spinal cord injury. The findings, published online today in Cell Stem Cell, could offer hope for the hundreds of thousands of people worldwide who suffer a spinal cord injury each year.

Cells in some body tissues proliferate after injury, replacing dead or damaged cells as part of healing. However, explains study leader END ...

What The Study Did: The objectives of this study were to examine the characteristics and outcomes among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 at U.S. medical centers and analyze changes in mortality over the initial six months of the pandemic.

Authors: Ninh T. Nguyen, M.D., of the University of California, Irvine Medical Center, in Orange, is the corresponding author.

To access the embargoed study: Visit our For The Media website at this link https://media.jamanetwork.com/

(doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0417)

Editor's Note: The article includes ...