(Press-News.org) A massive effort to map the precise binding locations of over 400 different kinds of proteins on the yeast genome has produced the most thorough and high-resolution map of chromosome architecture and gene regulation to date. The study reveals two distinct gene regulatory architectures, expanding the traditional model of gene regulation. So-called constitutive genes, those that perform basic 'housekeeping' functions and are nearly always active at low levels require only a basic set of regulatory controls; whereas those that that are activated by environmental signals, known as inducible genes, have a more specialized architecture. This finding in yeast could open the door to a better understanding of the regulatory architecture of the human genome.

A paper describing the research by Penn State and Cornell University scientists appears March 10, 2021 in the journal Nature.

"When I first learned about DNA, I was taught to think of the genome as a library containing every book ever written," said Matthew J. Rossi, research assistant professor at Penn State and the first author of the paper. "The genome is stored as part of a complex of DNA, RNA and proteins, called 'chromatin.' The interactions of the proteins and DNA regulate when and where genes are expressed to produce RNA (i.e. reading a book to learn or make something specific). But what I always wondered was with all that complexity, how do you find the right book when you need it? That is the question we are trying to answer in this study."

How a cell chooses the right book depends on regulatory proteins and their interaction with DNA in chromatin, what can be referred to as the regulatory architecture of the genome. Yeast cells can respond to changes in their environment by altering this regulatory architecture to turn different genes on or off. In multicellular organisms, like humans, the difference between muscle cells, neurons, and every other cell type is determined by regulating the set of genes those cells are expressing. Deciphering the mechanisms that control this differential gene expression is therefore vital for understanding responses to the environment, organismal development, and evolution.

"Proteins need to be recruited and assembled at genes for them to be switched 'on,'" said B. Franklin Pugh, professor of molecular biology and genetics at Cornell University and a leader of the research project that was started when he was a professor at Penn State. "We've put together the most complete and high-resolution map of these proteins showing the locations that they bind to the yeast genome and revealing aspects of how they interact with each other to regulate gene expression."

The team used a technique called ChIP-exo, a high-resolution version of ChIP-seq, to precisely and reproducibly map the binding locations of about 400 different proteins that interact with the yeast genome, some at a few locations and others at thousands of locations. In ChIP-exo, proteins are chemically cross-linked to the DNA inside living cells, thereby locking them into position. The chromosomes are then removed from cells and sheared into smaller pieces. Antibodies are used to capture specific proteins and the piece of DNA to which they are bound. The location of the protein-DNA interaction can then be found by sequencing the DNA attached to the protein and mapping the sequence back to the genome.

"In traditional ChIP-seq, the pieces of DNA attached to the proteins are still rather large and variable in length--ranging anywhere from 100 to 500 base pairs beyond the actual protein binding site," said William K.M. Lai, assistant research professor at Cornell University and an author of the paper. "In ChIP-exo, we add an additional step of trimming the DNA with an enzyme called an exonuclease. This removes any excess DNA that is not protected by the cross-linked protein, allowing us to get a much more precise location for the binding event and to better visualize interactions among the proteins."

The team performed over 1,200 individual ChIP-exo experiments producing billions of individual points of data. Analysis of the massive data leveraged Penn State's supercomputing clusters and required the development of several novel bioinformatic tools including a multifaceted computational workflow designed to identify patterns and reveal the organization of regulatory proteins in the yeast genome.

The analysis, which is akin to picking out repeated types of features on the ground from hundreds of satellite images, revealed a surprisingly small number of unique protein assemblages that are used repeatedly across the yeast genome.

"The resolution and completeness of the data allowed us to identify 21 protein assemblages and also to identify the absence of specific regulatory control signals at housekeeping genes," said Shaun Mahony, assistant professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at Penn State and an author of the paper. "The computational methods that we've developed to analyze this data could serve as a jumping off point for further development for gene regulatory studies in more complex organisms."

The traditional model of gene regulation involves proteins called 'transcription factors' that bind to specific DNA sequences to control the expression of a nearby gene. However, the researchers found that the majority of genes in yeast do not adhere to this model.

"We were surprised to find that housekeeping genes lacked a protein-DNA architecture that would allow specific transcription factors to bind, which is the hallmark of inducible genes," said Pugh. "These genes just seem to need a general set of proteins that allow access to the DNA and its transcription without much need for regulation. Whether or not this pattern holds up in multicellular organisms like humans is yet to be seen. It's a vastly more complex proposition, but like the sequencing of the yeast genome preceded the sequencing of the human genome, I'm sure we will eventually be able to see the regulatory architecture of the human genome at high resolution."

INFORMATION:

In addition to Rossi, Pugh, Lai, and Mahony, the research team includes Prashant K. Kuntala, Naomi Yamada, Nitika Badjatia, Chitvan Mittal, Guray Kuzu, Kylie Bocklund, Nina P. Farrell, Thomas R. Blanda, Joshua D. Mairose, Ann V. Basting, Katelyn S. Mistretta, David J. Rocco, Emily S. Perkinson, and Gretta D. Kellogg.

This work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the U.S. National Science Foundation, the Penn State Institute for Computational and Data Sciences, and Advanced CyberInfrastructure (ROAR) at Penn State.

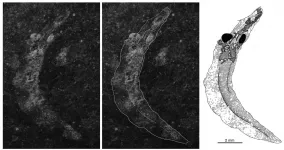

The unprecedented discovery of an ancient lamprey growth series, published in the prestigious scientific journal, Nature, is overturning long-held ideas as to what modern lampreys may tell us about the origin of vertebrates (all animals with a backbone such as goldfish, lizards, crows and people).

"Lampreys and modern hagfish are the only jawless fish alive that branched off from the family tree of vertebrates before they got jaws," says Dr Rob Gess from the Albany Museum in Makhanda, who discovered the ancient fossils. "This makes them very interesting for researchers attempting to understand the earliest stages of vertebrate history."

Until now, it was commonly believed that modern lampreys were swimming ...

The unpredictable nature of life during the coronavirus pandemic is particularly challenging for many people. Not everyone can cope equally well with the uncertainty and loss of control. Research has shown that while a large segment of the population turns out to be resilient in times of stress and potentially traumatic events, others are less robust and develop stress-related illnesses. Events that some people experience as draining seem to be a source of motivation and creativity for others.

These differing degrees of resilience demonstrate that people recover from stressful events ...

In a study recently published in Nature Communications, scientists from The Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Biosustainability (DTU) and Yale University have investigated how bacteria that are commonly found in sugarcane ethanol fermentation affect the industrial process. By closely studying the interactions between yeast and bacteria, it is suggested that the industry could improve both its total yield and the cost of the fermentation processes by paying more attention to the diversity of the microbial communities and choosing between good and bad bacteria.

The scientists dissected yeast-bacteria interactions in sugarcane ethanol fermentation by reconstituting every possible combination ...

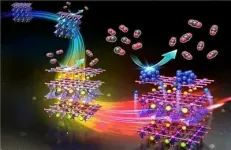

Fuel cells, which are attracting attention as an eco-friendly energy source, obtain electricity and heat simultaneously through the reverse reaction of water electrolysis. Therefore, the catalyst that enhances the reaction efficiency is directly connected to the performance of the fuel cell. To this, a POSTECH-UNIST joint research team has taken a step closer to developing high-performance catalysts by uncovering the ex-solution and phase transition phenomena at the atomic level for the first time.

A joint research team of Professor Jeong Woo Han and Ph.D. candidate Kyeounghak Kim of POSTECH's Department of Chemical Engineering, and Professor Guntae Kim of UNIST have uncovered the mechanism by which PBMO - a catalyst used ...

Italian and Russian researchers confirmed the hypothesis that the self-maintaining order in eukaryotic cells (cells with nuclei) is a result of two spontaneous mechanisms' collaboration. Similar molecules gather into 'drops' on the membrane and then leave it as tiny vesicles enriched by the collected molecules. The paper with the research results was published in the journal Physical Review Letters.

The research was carried out by an international interdisciplinary team of biologists (from Polytechnic University of Turin, Italian Institute for Genomic Medicine of the University of Turin and Candiolo Cancer Institute) and ...

Variant B.1.1.7 of COVID-19 associated with a significantly higher mortality rate, research shows

The highly infectious variant of COVID-19 discovered in Kent, which swept across the UK last year before spreading worldwide, is between 30 and 100 per cent more deadly than previous strains, new analysis has shown.

A pivotal study, by epidemiologists from the Universities of Exeter and Bristol, has shown that the SARS-CoV-2 variant, B.1.1.7, is associated with a significantly higher mortality rate amongst adults diagnosed in the community compared to previously circulating strains.

The study compared death rates among people infected ...

Newly published research has revealed a close link between proteins associated with Alzheimer's disease and age-related sight loss. The findings could open the way to new treatments for patients with deteriorating vision and through this study, the scientists believe they could reduce the need for using animals in future research into blinding conditions.

Amyloid beta (AB) proteins are the primary driver of Alzheimer's disease but also begin to collect in the retina as people get older. Donor eyes from patients who suffered from age-related macular degeneration (AMD), the most common cause of blindness amongst adults in the UK, have been shown to contain high levels of AB in their retinas.

This new study, published in the journal Cells, builds on previous ...

The Telomeres and Telomerase Group led by Maria A. Blasco at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO) continues to make progress in unravelling the role that telomeres -the ends of chromosomes that are responsible for cellular ageing as they shorten- play in cancer. The CNIO team was among the first to propose that shelterins, proteins that wrap around telomeres and act as a protective shield, might be therapeutic targets for cancer treatment. Subsequently, they found that eliminating one of these shelterins, TRF1, blocks the initiation and progression of lung cancer and glioblastoma in mouse models and prevents glioblastoma stem cells from forming secondary tumours. Now, in a study published in PLOS Genetics, ...

People with aphantasia - that is, the inability to visualise mental images - are harder to spook with scary stories, a new UNSW Sydney study shows.

The study, published today in Proceedings of the Royal Society B, tested how aphantasic people reacted to reading distressing scenarios, like being chased by a shark, falling off a cliff, or being in a plane that's about to crash.

The researchers were able to physically measure each participant's fear response by monitoring changing skin conductivity levels - in other words, how much the story made a person sweat. This type of test is commonly ...

WESTMINSTER, Colorado - March 10, 2021 - The paperbark tree (Melaleuca quinquenervia) was introduced to the U.S. from Australia in the 1900s. Unfortunately, it went on to become a weedy invader that has dominated natural landscapes across southern Florida, including the fragile wetlands of the Everglades.

According to an article in the journal END ...