Vaccine-induced antibodies may be less effective against several new SARS-CoV-2 variants

Researchers at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard and at Massachusetts General Hospital find that neutralizing antibodies raised by COVID-19 vaccines are not as effective at neutralizing some new, circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants

2021-03-12

(Press-News.org) BOSTON -- SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has mutated throughout the pandemic. New variants of the virus have arisen throughout the world, including variants that might possess increased ability to spread or evade the immune system. Such variants have been identified in California, Denmark, the U.K., South Africa and Brazil/Japan. Understanding how well the COVID-19 vaccines work against these variants is vital in the efforts to stop the global pandemic, and is the subject of new research from the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a study recently published in Cell, Ragon Core Member Alejandro Balazs, PhD, found that the neutralizing antibodies induced by the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines were significantly less effective against the variants first described in Brazil/Japan and South Africa. Balazs's team used their experience measuring HIV neutralizing antibodies to create similar assays for COVID-19, comparing how well the antibodies worked against the original strain versus the new variants.

"We were able to leverage the unique high-throughput capacity that was already in place and apply it to SARS-CoV-2," says Balazs, who is also an assistant professor of Medicine at Harvard Medical School and assistant investigator in the Department of Medicine at MGH. "When we tested these new strains against vaccine-induced neutralizing antibodies, we found that the three new strains first described in South Africa were 20-40 times more resistant to neutralization, and the two strains first described in Brazil and Japan were five to seven times more resistant, compared to the original SARS-CoV-2 virus."

Neutralizing antibodies, explains Balazs, work by binding tightly to the virus and blocking it from entering cells, thus preventing infection. Like a key in a lock, this binding only happens when the antibody's shape and the virus's shape are perfectly matched to each other. If the shape of the virus changes where the antibody attaches to it - in this case, in SARS-CoV-2's spike protein - then the antibody may no longer be able to recognize and neutralize the virus as well. The virus would then be described as resistant to neutralization.

"In particular," says Wilfredo Garcia-Beltran, MD, PhD, a resident physician in the Department of Pathology at MGH and first author of the study, "we found that mutations in a specific part of the spike protein called the receptor binding domain were more likely to help the virus resist the neutralizing antibodies." The three South African variants, which were the most resistant, all shared three mutations in the receptor binding domain. This may contribute to their high resistance to neutralizing antibodies.

Currently, all approved COVID-19 vaccines work by teaching the body to produce an immune response, including antibodies, against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. While the ability of these variants to resist neutralizing antibodies is concerning, it doesn't mean the vaccines won't be effective.

"The body has other methods of immune protection besides antibodies," says Balazs. "Our findings don't necessarily mean that vaccines won't prevent COVID, only that the antibody portion of the immune response may have trouble recognizing some of these new variants."

Like all viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is expected to continue to mutate as it spreads. Understanding which mutations are most likely to allow the virus to evade vaccine-derived immunity can help researchers develop next-generation vaccines that can provide protection against new variants. It can also help researchers develop more effective preventative methods, such as broadly protective vaccines that work against a wide variety of variants, regardless of which mutations develop.

INFORMATION:

About the Ragon Institute

The Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard was established in 2009 with a gift from the Phillip T. and Susan M. Ragon Foundation, with a collaborative scientific mission among these institutions to harness the immune system to combat and cure human diseases. Focusing on global infectious diseases, the Ragon Institute draws scientists, clinicians and engineers from diverse backgrounds and areas of expertise to study and understand the immune system with the goal of benefiting patients. For more information, visit http://www.ragoninstitute.org

About the Massachusetts General Hospital

Massachusetts General Hospital, founded in 1811, is the original and largest teaching hospital of Harvard Medical School. The Mass General Research Institute conducts the largest hospital-based research program in the nation, with annual research operations of more than $1 billion and comprises more than 9,500 researchers working across more than 30 institutes, centers and departments. In August 2020, Mass General was named #6 in the U.S. News & World Report list of "America's Best Hospitals."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-03-12

Orono, Maine -- The origins of ice age climate changes may lie in the Southern Hemisphere, where interactions among the westerly wind system, the Southern Ocean and the tropical Pacific can trigger rapid, global changes in atmospheric temperature, according to an international research team led by the University of Maine.

The mechanism, dubbed the Zealandia Switch, relates to the general position of the Southern Hemisphere westerly wind belt -- the strongest wind system on Earth -- and the continental platforms of the southwest Pacific Ocean, and their control on ocean currents. Shifts in the latitude of the westerly winds affects the strength ...

2021-03-12

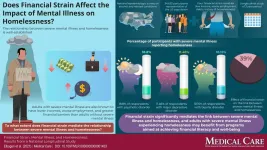

March 12, 2021 - Financial strains like debt or unemployment are significant risk factors for becoming homeless, and even help to explain increased risk of homelessness associated with severe mental illness, reports a study in a supplement to the April issue of Medical Care. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings "suggest that adding financial well-being as a focus of homelessness prevention efforts seems promising, both at the individual and community level," according to the new research, led by Eric Elbogen, PhD, of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center on Homelessness and Duke University School of Medicine. The study appears as part of a special issue on ...

2021-03-12

Mantle cell lymphoma is a malignant disease in which intensive treatment can prolong life. In a new study, scientists from Uppsala University and other Swedish universities show that people with mantle cell lymphoma who were unmarried, and those who had low educational attainment, were less often treated with a stem-cell transplantation, which may result in poorer survival. The findings have been published in the scientific journal Blood Advances.

Patients diagnosed with a mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) where the disease has spread receive intensive treatment with cytotoxic drugs and stem-cell transplantation. In a new study, researchers looked at which people are more likely to be offered transplants, and compared survival between those ...

2021-03-12

WINSTON-SALEM, NC - March 12, 2021 - The Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine is investigating how cats with chronic kidney disease could someday help inform treatment for humans.

In humans, treatment for chronic kidney disease -- a condition in which the kidneys are damaged and cannot filter blood as well as they should -- focuses on slowing the progression of the organ damage. The condition can progress to end-stage kidney failure, which is fatal without dialysis or a kidney transplant. An estimated 37 million people in the US suffer from chronic kidney disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates there are about 58 million ...

2021-03-12

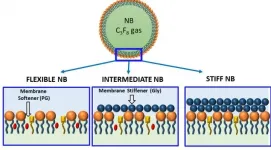

If you were given "ultrasound" in a word association game, "sound wave" might easily come to mind. But in recent years, a new term has surfaced: bubbles. Those ephemeral, globular shapes are proving useful in improving medical imaging, disease detection and targeted drug delivery. There's just one glitch: bubbles fizzle out soon after injection into the bloodstream.

Now, after 10 years' work, a multidisciplinary research team has built a better bubble. Their new formulations have resulted in nanoscale bubbles with customizable outer shells -- so small and durable that they can travel to and penetrate some of the ...

2021-03-12

(BOSTON) -- There is a great need to generate various types of cells for use in new therapies to replace tissues that are lost due to disease or injuries, or for studies outside the human body to improve our understanding of how organs and tissues function in health and disease. Many of these efforts start with human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that, in theory, have the capacity to differentiate into virtually any cell type in the right culture conditions. The 2012 Nobel Prize awarded to Shinya Yamanaka recognized his discovery of a strategy that can reprogram adult cells to become iPSCs ...

2021-03-12

Arlington, Va. (March 12, 2021)--A new supplement offering guidance on severe COVID-19 management in resource-limited settings is now available on the American Journal of Tropical Medicine (AJTMH) website. Pragmatic Recommendations for the Management of Hospitalized COVID-19 Patients in Low- and Middle-Income Countries was coordinated by a COVID-LMIC Task Force headed by Alfred Papali, MD, of Atrium Health, Charlotte, NC, and Marcus Schultz, MD, PhD, of Mahidol University, Bangkok, Thailand; University of Oxford, United Kingdom; and Amsterdam University Medical Centers, The Netherlands. ...

2021-03-12

BUFFALO, N.Y. - University at Buffalo computer scientists have developed a tool that automatically identifies deepfake photos by analyzing light reflections in the eyes.

The tool proved 94% effective in experiments described in a paper accepted at the IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing to be held in June in Toronto, Canada.

"The cornea is almost like a perfect semisphere and is very reflective," says the paper's lead author, Siwei Lyu, PhD, SUNY Empire Innovation Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering. "So, anything that is coming to the eye with a light emitting from those sources will have an image on ...

2021-03-12

Reston, VA--Immuno-positron emission tomography (PET) imaging can provide early insight into a tumor's response to targeted therapy, allowing physicians to select the most effective treatment for patients who have cancer. The new research was published in the March issue of The Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

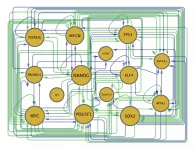

The research showed that immuno-PET successfully visualizes changes in different cancer receptors (receptor tyrosine kinases, or RTKs) within tumors during targeted therapies. This gives physicians a tool that can be used to evaluate the effectiveness of a treatment soon after its administration.

"When healthy cells turn into cancer cells, there is a disruption in the RTK signaling. This makes RTKs a valuable therapeutic and ...

2021-03-12

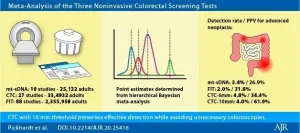

Leesburg, VA, March 12, 2021--According to an open-access article in ARRS' American Journal of Roentgenology (AJR), compared with multi-target stool-DNA (mt-sDNA) and fecal immunochemical test (FIT), CT colonography (CTC) with 10 mm threshold most effectively targets advanced neoplasia (AN)--preserving detection while decreasing unnecessary colonoscopies.

"CTC performed with a polyp size threshold for colonoscopy referral set at 10 mm represents the most effective and efficient non-invasive screening test for colorectal cancer (CRC) prevention and detection," clarified first author Perry J. Pickhardt from the department of radiology ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Vaccine-induced antibodies may be less effective against several new SARS-CoV-2 variants

Researchers at the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard and at Massachusetts General Hospital find that neutralizing antibodies raised by COVID-19 vaccines are not as effective at neutralizing some new, circulating SARS-CoV-2 variants