(Press-News.org) DURHAM, N.C. -- If you binged on high-calorie snacks and then spent the winter crashed on the couch in a months-long food coma, you'd likely wake up worse for wear. Unless you happen to be a fat-tailed dwarf lemur.

This squirrel-sized primate lives in the forests of Madagascar, where it spends up to seven months each year mostly motionless and chilling, using the minimum energy necessary to withstand the winter. While zonked, it lives off of fat stored in its tail.

Animals that hibernate in the wild rarely do so in zoos and sanctuaries, with their climate controls and year-round access to food. But now our closest hibernating relative has gone into true, deep hibernation in captivity for the first time at the Duke Lemur Center.

"They did not disappoint," said research scientist Marina Blanco, who led the project. "Indeed, our dwarf lemurs hibernated just like their wild kin do in western Madagascar."

The researchers say recreating some of the seasonal fluctuations of the lemurs' native habitat might be good for the well-being of a species hardwired for hibernation, and also may yield insights into metabolic disorders in humans.

"Hibernation is literally in their DNA," Blanco said.

Blanco has studied dwarf lemurs for 15 years in Madagascar, fitting them with tracking collars to locate them when they are hibernating in their tree holes or underground burrows. But what she and others observed in the wild didn't square with how the animals behaved when cared for in captivity.

Captive dwarf lemurs are fed extra during the summer so they can bulk up like they do in the wild, and then they'll hunker down and let their heart rate and temperature drop for short bouts -- a physiological condition known as torpor. But they rarely stay in this suspended state for longer than 24 hours. Which got Blanco to wondering: After years in captivity, do dwarf lemurs still have what it takes to survive seasonal swings like their wild counterparts do? And what can these animals teach us about how to safely put the human body on pause too, slowing the body's processes long enough for, say, life-saving surgery or even space travel?

To find out, Duke Lemur Center staff teamed up to build fake tree hollows out of wooden boxes and placed them in the dwarf lemurs' indoor enclosures, as a haven for them to wait out the winter. To mimic the seasonal changes the lemurs experience over the course of the year in Madagascar, the team also gradually adjusted the lights from 12 hours a day to a more "winter-like" 9.5 hours, and lowered the thermostat from 77 degrees Fahrenheit to the low 50s.

The animals were offered food if they were awake and active, and weighed every two weeks, but otherwise they were left to lie.

It worked. In the March 11 issue of the journal Scientific Reports, the researchers show for the first time that fat-tailed dwarf lemurs can hibernate quite well in captivity.

For four months, the eight lemurs in the study spent some 70% of their time in metabolic slow-motion: curled up, cool to the touch, barely moving or breathing for up to 11 days at a stretch, showing little interest in food -- akin to their wild counterparts.

Now that spring is afoot in North Carolina and the temperatures are warming, the lemurs are waking up. Their first physical exams after they emerged showed them to be 22% to 35% lighter than they were at the start but otherwise healthy. Their heart rates are back up from just eight beats per minute to about 200, and their appetites have returned.

"We've been able to replicate their wild conditions well enough to get them to replicate their natural patterns," said Erin Ehmke, who directs research at the center.

Females were the hibernation champs, out-stuporing the males and maintaining more of their winter weight. They need what's left of their fat stores for the months of pregnancy and lactation that typically follow after they wake up, Blanco said.

Study co-author Lydia Greene says the next step is to use non-invasive research techniques such as metabolite analysis and sensors in their enclosures to better understand what dwarf lemurs do to prepare their bodies and eventually bounce back from months of standby mode -- work that could lead to new treatments for heart attacks, strokes, and other life-threatening conditions in humans.

Blanco suspects the impressive energy-saving capabilities of these lemurs may also relate to another trait they possess: longevity. The oldest dwarf lemur on record, Jonas, died at the Duke Lemur Center at the age of 29. The fact that dwarf lemurs live longer than non-hibernating species their size suggests that something intrinsic to their biological machinery may protect against aging.

"But until now, if you wanted to study hibernation in these primates, you needed to go to Madagascar to find them in the act," Blanco said. "Now we can study hibernation here and do more close monitoring."

INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the Duke Lemur Center.

CITATION: "On the Modulation and Maintenance of Hibernation in Captive Dwarf Lemurs," Marina B. Blanco, Lydia K. Greene, Robert Schopler, Cathy V. Williams, Danielle Lynch, Jenna Browning, Kay Welser, Melanie Simmons, Peter H. Klopfer, Erin E. Ehmke. Scientific Reports, March 11, 2021. DOI: 10.1038/s41598-021-84727-3.

Decades of feminist gains in the workforce have been undermined by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has upended public education across the United States, a critical infrastructure of care that parents -- especially mothers -- depend on to work, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

The research, published in Gender & Society, draws on new data from the Elementary School Operating Status (ESOS) database to show that the gender gap between mothers and fathers in the labor force has grown significantly since the onset of the pandemic in states where schools primarily offered remote instruction.

And if these circumstances continue, it could deliver ...

Sound sleep plays a critical role in healing traumatic brain injury, a new study of military veterans suggests.

The study, published in the Journal of Neurotrauma, used a new technique involving magnetic resonance imaging developed at Oregon Health & Science University. Researchers used MRI to evaluate the enlargement of perivascular spaces that surround blood vessels in the brain. Enlargement of these spaces occurs in aging and is associated with the development of dementia.

Among veterans in the study, those who slept poorly had more evidence of these enlarged spaces and more post-concussive symptoms.

"This has huge implications for the armed forces as well as civilians," said lead author Juan Piantino, M.D., MCR, assistant professor of pediatrics (neurology) in the ...

Astronomers have painted their best picture yet of an RV Tauri variable, a rare type of stellar binary where two stars - one approaching the end of its life - orbit within a sprawling disk of dust. Their 130-year dataset spans the widest range of light yet collected for one of these systems, from radio to X-rays.

"There are only about 300 known RV Tauri variables in the Milky Way galaxy," said Laura Vega, a recent doctoral recipient at Vanderbilt University in Nashville, Tennessee. "We focused our study on the second brightest, named U Monocerotis, which is now the first of these systems from which X-rays have been detected."

A paper describing the findings, led by Vega, was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

The system, called U ...

Water is perhaps Earth's most critical natural resource. Given increasing demand and increasingly stretched water resources, scientists are pursuing more innovative ways to use and reuse existing water, as well as to design new materials to improve water purification methods. Synthetically created semi-permeable polymer membranes used for contaminant solute removal can provide a level of advanced treatment and improve the energy efficiency of treating water; however, existing knowledge gaps are limiting transformative advances in membrane technology. One basic problem is ...

BOSTON -- SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, has mutated throughout the pandemic. New variants of the virus have arisen throughout the world, including variants that might possess increased ability to spread or evade the immune system. Such variants have been identified in California, Denmark, the U.K., South Africa and Brazil/Japan. Understanding how well the COVID-19 vaccines work against these variants is vital in the efforts to stop the global pandemic, and is the subject of new research from the Ragon Institute of MGH, MIT and Harvard and Massachusetts General Hospital.

In a study recently published in Cell, Ragon Core Member Alejandro Balazs, PhD, found that the neutralizing antibodies induced by the ...

Orono, Maine -- The origins of ice age climate changes may lie in the Southern Hemisphere, where interactions among the westerly wind system, the Southern Ocean and the tropical Pacific can trigger rapid, global changes in atmospheric temperature, according to an international research team led by the University of Maine.

The mechanism, dubbed the Zealandia Switch, relates to the general position of the Southern Hemisphere westerly wind belt -- the strongest wind system on Earth -- and the continental platforms of the southwest Pacific Ocean, and their control on ocean currents. Shifts in the latitude of the westerly winds affects the strength ...

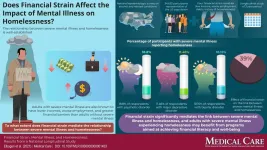

March 12, 2021 - Financial strains like debt or unemployment are significant risk factors for becoming homeless, and even help to explain increased risk of homelessness associated with severe mental illness, reports a study in a supplement to the April issue of Medical Care. The journal is published in the Lippincott portfolio by Wolters Kluwer.

The findings "suggest that adding financial well-being as a focus of homelessness prevention efforts seems promising, both at the individual and community level," according to the new research, led by Eric Elbogen, PhD, of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) National Center on Homelessness and Duke University School of Medicine. The study appears as part of a special issue on ...

Mantle cell lymphoma is a malignant disease in which intensive treatment can prolong life. In a new study, scientists from Uppsala University and other Swedish universities show that people with mantle cell lymphoma who were unmarried, and those who had low educational attainment, were less often treated with a stem-cell transplantation, which may result in poorer survival. The findings have been published in the scientific journal Blood Advances.

Patients diagnosed with a mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) where the disease has spread receive intensive treatment with cytotoxic drugs and stem-cell transplantation. In a new study, researchers looked at which people are more likely to be offered transplants, and compared survival between those ...

WINSTON-SALEM, NC - March 12, 2021 - The Wake Forest Institute for Regenerative Medicine is investigating how cats with chronic kidney disease could someday help inform treatment for humans.

In humans, treatment for chronic kidney disease -- a condition in which the kidneys are damaged and cannot filter blood as well as they should -- focuses on slowing the progression of the organ damage. The condition can progress to end-stage kidney failure, which is fatal without dialysis or a kidney transplant. An estimated 37 million people in the US suffer from chronic kidney disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The American Veterinary Medical Association estimates there are about 58 million ...

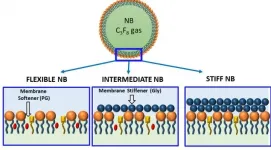

If you were given "ultrasound" in a word association game, "sound wave" might easily come to mind. But in recent years, a new term has surfaced: bubbles. Those ephemeral, globular shapes are proving useful in improving medical imaging, disease detection and targeted drug delivery. There's just one glitch: bubbles fizzle out soon after injection into the bloodstream.

Now, after 10 years' work, a multidisciplinary research team has built a better bubble. Their new formulations have resulted in nanoscale bubbles with customizable outer shells -- so small and durable that they can travel to and penetrate some of the ...