INFORMATION:

This research was supported, in part, by the VoLo Foundation, the Simons Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Study predicts the oceans will start emitting ozone-depleting CFCs

As atmospheric concentrations of CFC-11 drop, the global ocean should become a source of the chemical by the middle of next century.

2021-03-15

(Press-News.org) The world's oceans are a vast repository for gases including ozone-depleting chlorofluorocarbons, or CFCs. They absorb these gases from the atmosphere and draw them down to the deep, where they can remain sequestered for centuries and more.

Marine CFCs have long been used as tracers to study ocean currents, but their impact on atmospheric concentrations was assumed to be negligible. Now, MIT researchers have found the oceanic fluxes of at least one type of CFC, known as CFC-11, do in fact affect atmospheric concentrations. In a study appearing today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the team reports that the global ocean will reverse its longtime role as a sink for the potent ozone-depleting chemical.

The researchers project that by the year 2075, the oceans will emit more CFC-11 back into the atmosphere than they absorb, emitting detectable amounts of the chemical by 2130. Further, with increasing climate change, this shift will occur 10 years earlier. The emissions of CFC-11 from the ocean will effectively extend the chemical's average residence time, causing it to linger five years longer in the atmosphere than it otherwise would. This may impact future estimations of CFC-11 emissions.

The new results may help scientists and policymakers better pinpoint future sources of the chemical, which is now banned worldwide under the Montreal Protocol.

"By the time you get to the first half of the 22nd century, you'll have enough of a flux coming out of the ocean that it might look like someone is cheating on the Montreal Protocol, but instead, it could just be what's coming out of the ocean," says study co-author Susan Solomon, the Lee and Geraldine Martin Professor of Environmental Studies in MIT's Department of Earth, Atmospheric and Planetary Sciences. "It's an interesting prediction and hopefully will help future researchers avoid getting confused about what's going on."

Solomon's co-authors include lead author Peidong Wang, Jeffery Scott, John Marshall, Andrew Babbin, Megan Lickley, and Ronald Prinn from MIT; David Thompson of Colorado State University; Timothy DeVries of the University of California at Santa Barbara; and Qing Liang of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

An ocean, oversaturated

CFC-11 is a chlorofluorocarbon that was commonly used to make refrigerants and insulating foams. When emitted to the atmosphere, the chemical sets off a chain reaction that ultimately destroys ozone, the atmospheric layer that protects the Earth from harmful ultraviolet radiation. Since 2010, the production and use of the chemical has been phased out worldwide under the Montreal Protocol, a global treaty that aims to restore and protect the ozone layer.

Since its phaseout, levels of CFC-11 in the atmosphere have been steadily declining, and scientists estimate that the ocean has absorbed about 5 to 10 percent of all manufactured CFC-11 emissions. As concentrations of the chemical continue to fall in the atmosphere, however, it's predicted that CFC-11 will oversaturate in the ocean, pushing it to become a source rather than a sink.

"For some time, human emissions were so large that what was going into the ocean was considered negligible," Solomon says. "Now, as we try to get rid of human emissions, we find we can't completely ignore what the ocean is doing anymore."

A weakening reservoir

In their new paper, the MIT team looked to pinpoint when the ocean would become a source of the chemical, and to what extent the ocean would contribute to CFC-11 concentrations in the atmosphere. They also sought to understand how climate change would impact the ocean's ability to absorb the chemical in the future.

The researchers used a hierarchy of models to simulate the mixing within and between the ocean and atmosphere. They began with a simple model of the atmosphere and the upper and lower layers of the ocean, in both the northern and southern hemispheres. They added into this model anthropogenic emissions of CFC-11 that had previously been reported through the years, then ran the model forward in time, from 1930 to 2300, to observe changes in the chemical's flux between the ocean and the atmosphere.

They then replaced the ocean layers of this simple model with the MIT general circulation model, or MITgcm, a more sophisticated representation of ocean dynamics, and ran similar simulations of CFC-11 over the same time period.

Both models produced atmospheric levels of CFC-11 through the present day that matched with recorded measurements, giving the team confidence in their approach. When they looked at the models' future projections, they observed that the ocean began to emit more of the chemical than it absorbed, beginning around 2075. By 2145, the ocean would emit CFC-11 in amounts that would be detectable by current monitoring standards.

The ocean's uptake in the 20th century and outgassing in the future also affects the chemical's effective residence time in the atmosphere, decreasing it by several years during uptake and increasing it by up to 5 years by the end of 2200.

Climate change will speed up this process. The team used the models to simulate a future with global warming of about 5 degrees Celsius by the year 2100, and found that climate change will advance the ocean's shift to a source by 10 years and produce detectable levels of CFC-11 by 2140.

"Generally, a colder ocean will absorb more CFCs," Wang explains. "When climate change warms the ocean, it becomes a weaker reservoir and will also outgas a little faster."

"Even if there were no climate change, as CFCs decay in the atmosphere, eventually the ocean has too much relative to the atmosphere, and it will come back out," Solomon adds. "Climate change, we think, will make that happen even sooner. But the switch is not dependent on climate change."

Their simulations show that the ocean's shift will occur slightly faster in the Northern Hemisphere, where large-scale ocean circulation patterns are expected to slow down, leaving more gases in the shallow ocean to escape back to the atmosphere. However, knowing the exact drivers of the ocean's reversal will require more detailed models, which the researchers intend to explore.

"Some of the next steps would be to do this with higher-resolution models and focus on patterns of change," says Scott. "For now, we've opened up some great new questions and given an idea of what one might see."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Scientists stunned to discover plants beneath mile-deep Greenland ice

2021-03-15

In 1966, US Army scientists drilled down through nearly a mile of ice in northwestern Greenland--and pulled up a fifteen-foot-long tube of dirt from the bottom. Then this frozen sediment was lost in a freezer for decades. It was accidentally rediscovered in 2017.

In 2019, University of Vermont scientist Andrew Christ looked at it through his microscope--and couldn't believe what he was seeing: twigs and leaves instead of just sand and rock. That suggested that the ice was gone in the recent geologic past--and that a vegetated landscape, perhaps a boreal forest, stood where a mile-deep ice sheet as big ...

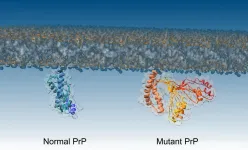

Crucial step in formation of deadly brain diseases discovered

2021-03-15

For the first time, researchers have pinpointed what causes normal proteins to convert to a diseased form, causing conditions like CJD and Kuru.

The research team, from Imperial College London and the University of Zurich, also tested a way to block the process, which could lead to new drugs for combatting these diseases.

The research concerned prion diseases - a group of brain diseases caused by proteins called prions that malfunction and 'misfold', turning into a form that can accumulate and kill brain cells. These diseases can take decades to manifest, but are then are aggressive and fatal.

They include Kuru, mad cow disease and its human equivalent Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), and a heritable condition called fatal familial ...

Race influences flood risk behaviors

2021-03-15

If you live in a flood prone area, would you -- or could you -- take measures to mitigate flood risks? What about others in your community? We are running out of time to ask this question according to The World Resources Institute, because global flood risk is increasing and loss projections for rivers alone put the cost over 500 billion dollars by midcentury.

Research published today in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences from scientists from the University of Connecticut, the University of Maryland's National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC), the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and the London School of Economics suggests that in the United States, race and stream flow are ...

How novel pathogens may cause the development of colorectal cancer

2021-03-15

Do BMMFs, the novel infectious agents found in dairy products and bovine sera, play a role in the development of colorectal cancer? Scientists led by Harald zur Hausen detected the pathogens in colorectal cancer patients in close proximity to tumors. The researchers show that the BMMFs trigger local chronic inflammation, which can cause mutations via activated oxygen molecules and thus promote cancer development in the long term. BMMFs and inflammatory markers were significantly more frequently detectable in the vicinity of malignant intestinal tumors than in the intestinal tissue of tumor-free individuals.

A few years ago, ...

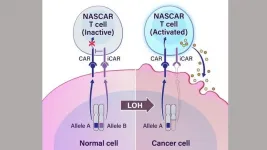

Cancer immunotherapy approach targets common genetic alteration

2021-03-15

Researchers developed a prototype for a new cancer immunotherapy that uses engineered T cells to target a genetic alteration common among all cancers. The approach, which stimulates an immune response against cells that are missing one gene copy, called loss of heterozygosity (LOH), was developed by researchers at the Ludwig Center, Lustgarten Laboratory and the Bloomberg~Kimmel Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center.

Genes have two alleles, or copies, with one copy inherited from each parent. Cancer-related genetic alterations commonly involve the loss of one of these gene copies.

"This copy loss, or LOH, is one of the most common genetic events in cancer," says Kenneth Kinzler, Ph.D., co-director of the Ludwig Center, professor of oncology and ...

Internet-access spending improves academic outcomes, according to study of Texas public schools

2021-03-15

HOUSTON - (March 15, 2021) - Increased internet-access spending by Texas public schools improved academic performance but also led to more disciplinary problems among students, a study of 9,000 schools conducted by a research team from Rice University, Texas A&M University and the University of Notre Dame shows.

Whether students benefit from increased internet access in public schools has been an open question, according to the researchers. For example, some parents and policy advocates contend it increases children's access to obscene or harmful content and disciplinary problems. Others believe it promotes personalized learning and higher student engagement.

To address these policy questions, the research team created a multiyear dataset (2000-14) of 1,243 school districts ...

University of Utah scientists plumb the depths of the world's tallest geyser

2021-03-15

When Steamboat Geyser, the world's tallest, started erupting again in 2018 in Yellowstone National Park after decades of relative silence, it raised a few tantalizing scientific questions. Why is it so tall? Why is it erupting again now? And what can we learn about it before it goes quiet again?

The University of Utah has been studying the geology and seismology of Yellowstone and its unique features for decades, so U scientists were ready to jump at the opportunity to get an unprecedented look at the workings of Steamboat Geyser. Their findings provide a picture of the depth of the geyser as well as a redefinition of a long-assumed relationship between the geyser and a nearby spring. The findings are published in the Journal of Geophysical Research-Solid Earth.

"We ...

Marketplace literacy as a pathway to a better world: evidence from field experiments

2021-03-15

If you are a consumer and/or entrepreneur who can make decisions based on cost, competition, supply and demand, you probably possess an element of marketplace literacy.

"Marketplace literacy" is defined as the knowledge and skills that enable individuals to participate in a marketplace both as consumers and entrepreneurs. San Diego State University marketing professor Nita Umashankar, along with professors Madhubalan Viswanathan (Loyola Marymount University), Arun Sreekumar (University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign) and Ashley Goreczny (Iowa State University), explored the impact on marketplace literacy on ...

How can new technologies help reduce the harm of drug use?

2021-03-15

HSE University researchers together with specialists from the Humanitarian Action Charitable Fund (St. Petersburg) and the University of Michigan School of Public Health (USA) studied the specifics of remote work with Russian people who use drugs to reduce the harm of drug use. They discovered that the use of online platforms increases the § who use drugs to seek help. Online platforms also serve as a kind of 'gateway' for people with problematic drug use to receive a wider range of qualified help. The authors concluded that remote work in this field should be developed and built upon in ...

Lessons learned in Burkina Faso can contribute to a new decade of forest restoration

2021-03-15

Forest landscape restoration is attaining new global momentum this year under the Decade of Ecosystem Restoration (2021-2030), an initiative launched by the United Nations. Burkina Faso, in West Africa, is one country that already has a head start in forest landscape restoration, and offers valuable lessons. An assessment of achievements there and in other countries with a history of landscape restoration is critical to informing a new wave of projects aiming for more ambitious targets that are being developed thanks to renewed global interest and political will to improve the environment.

Burkina Faso has been fighting with desertification and climate change, and has seen a progressive degradation of its forested landscapes due to the expansion of agriculture. In 2018, the country ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

COVID-19 vaccination during pregnancy may help prevent preeclampsia

Menopausal hormone therapy not linked to increased risk of death

Chronic shortage of family doctors in England, reveals BMJ analysis

Booster jabs reduce the risks of COVID-19 deaths, study finds

Screening increases survival rate for stage IV breast cancer by 60%

ACC announces inaugural fellow for the Thad and Gerry Waites Rural Cardiovascular Research Fellowship

University of Oklahoma researchers develop durable hybrid materials for faster radiation detection

Medicaid disenrollment spikes at age 19, study finds

Turning agricultural waste into advanced materials: Review highlights how torrefaction could power a sustainable carbon future

New study warns emerging pollutants in livestock and aquaculture waste may threaten ecosystems and public health

Integrated rice–aquatic farming systems may hold the key to smarter nitrogen use and lower agricultural emissions

Hope for global banana farming in genetic discovery

Mirror image pheromones help beetles swipe right

Prenatal lead exposure related to worse cognitive function in adults

Research alert: Understanding substance use across the full spectrum of sexual identity

Pekingese, Shih Tzu and Staffordshire Bull Terrier among twelve dog breeds at risk of serious breathing condition

Selected dog breeds with most breathing trouble identified in new study

Interplay of class and gender may influence social judgments differently between cultures

Pollen counts can be predicted by machine learning models using meteorological data with more than 80% accuracy even a week ahead, for both grass and birch tree pollen, which could be key in effective

Rewriting our understanding of early hominin dispersal to Eurasia

Rising simultaneous wildfire risk compromises international firefighting efforts

Honey bee "dance floors" can be accurately located with a new method, mapping where in the hive forager bees perform waggle dances to signal the location of pollen and nectar for their nestmates

Exercise and nutritional drinks can reduce the need for care in dementia

Michelson Medical Research Foundation awards $750,000 to rising immunology leaders

SfN announces Early Career Policy Ambassadors Class of 2026

Spiritual practices strongly associated with reduced risk for hazardous alcohol and drug use

Novel vaccine protects against C. diff disease and recurrence

An “electrical” circadian clock balances growth between shoots and roots

Largest study of rare skin cancer in Mexican patients shows its more complex than previously thought

Colonists dredged away Sydney’s natural oyster reefs. Now science knows how best to restore them.

[Press-News.org] Study predicts the oceans will start emitting ozone-depleting CFCsAs atmospheric concentrations of CFC-11 drop, the global ocean should become a source of the chemical by the middle of next century.