(Press-News.org) Many Mario Kart enthusiasts are familiar with the rush of racing down Rainbow Road, barely squeaking around a corner, and catching a power-up from one of the floating square icons on the screen--or, less ideally, slipping on a banana peel laid by another racer and flying off the side of the road into oblivion. This heated competition between multiple players, who use a variety of game tokens and tools to speed ahead or thwart their competitors, is part of what makes the classic Nintendo racing game that has been around since the early 1990s so appealing.

"It's been fun since I was a kid, it's fun for my kids, in part because anyone can play it," says Andrew Bell, a Boston University College of Arts & Sciences assistant professor of earth and environment. But as a researcher studying economic principles, Bell also sees Mario Kart as much more than just a racing game.

In a recent paper, Bell argues that the principles of Mario Kart--especially the parts of it that make it so addictive and fun for players--can serve as a helpful guide to create more equitable social and economic programs that would better serve farmers in low-resource, rural regions of the developing world. That's because, even when you're doing horribly in Mario Kart--flying off the side of Rainbow Road, for example--the game is designed to keep you in the race.

"Farming is an awful thing to have to do if you don't want to be a farmer," Bell says. "You have to be an entrepreneur, you have to be an agronomist, put in a bunch of labor...and in so many parts of the world people are farmers because their parents are farmers and those are the assets and options they had." This is a common story that Bell has come across many times during research trips to Pakistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, Malawi, and other countries in southern Africa, and is what largely inspired him to focus his research on policies that could aid in development.

In his new paper, Bell argues that policies that directly provide assistance to farmers in the world's poorest developing regions could help reduce poverty overall, while increasing sustainable and environmentally friendly practices. Bell says the idea is a lot like the way that Mario Kart gives players falling behind in the race the best power-ups, designed to bump them towards the front of the pack and keep them in the race. Meanwhile, faster players in the front don't get these same boosts, and instead typically get weaker powers, such as banana peels to trip up a racer behind them or an ink splat to disrupt the other players' screens. This boosting principle is called "rubber banding," and it's what keeps the game fun and interesting, Bell says, since there is always a chance for you to get ahead.

"And that's exactly what we want to do in development," he says. "And it is really, really difficult to do."

In the video game world, rubber banding is simple, since there are no real-world obstacles. But in the real world, the concept of rubber banding to extend financial resources to agricultural families and communities who need it the most is extremely complicated.

Those opportunities might look like this, Bell says: governments could set up a program so that a third party--such as a hydropower company--would pay farmers to adopt agricultural practices to help prevent erosion, so that the company can build a dam to provide electricity. It is a complicated transaction that has worked under very specific circumstances, Bell says, but systems like this--known as Payments for Ecosystem Services (PES)--have been successful in benefitting both the farmers and the environment. A major challenge is finding private companies that are willing to pay for ecosystem services, and connecting them with farmers who are willing to change their agricultural practices. The good news about rubber banding, though, is that the more people participate in such economic programs, the more other people will join in as well; a concept Bell calls "crowding in," in his analysis.

Bell says the biggest obstacle to overcome in most of the world's developing places is figuring out how to route assistance to people in need in the first place--because, until recently, many of the people were essentially living off the grid.

"It's hard to know who is in the back [of the pack]," Bell says.

But Bell says the ability to reach people in the lowest-resource areas has improved in the last decade or so, largely thanks to the adoption of mobile phones. (In another recent paper, Bell and his collaborators found that smartphones can also play a role in understanding and addressing food insecurity.) Now, mobile devices help local governments and organizations identify people searching for more prosperous livelihoods beyond the challenging practice of agriculture and reach out to those people with economic opportunities.

Bell says further expanding access to mobile devices in poor regions of the world would also allow the gap between the richest and poorest families to be better calculated, and could also help measure the success of newly implemented policies and programs.

"Mario Kart's rubber banding ethos is to target those in the back with the items that best help them to close their gap--their own 'golden mushrooms,'" Bell wrote in the paper, referring to the power-up that gives lagging racers powerful speed bursts. Improving environmental stewardship while alleviating poverty requires that researchers and decision-makers consider from the outset, "within their unique context and challenge at-large, what the golden mushroom might be."

INFORMATION:

Bell worked for International Food Policy Research Institute between 2012 and 2015, and then joined New York University's faculty as an assistant professor, where he began writing this paper. After six years at NYU, Bell joined BU to continue his research in sustainable development solutions in hard-to-reach places.

Whatever ultimately caused inhabitants to abandon Cahokia, it was not because they cut down too many trees, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

Archaeologists from Arts & Sciences excavated around earthen mounds and analyzed sediment cores to test a persistent theory about the collapse of Cahokia, the pre-Columbian Native American city in southwestern Illinois that was once home to more than 15,000 people.

No one knows for sure why people left Cahokia, though many environmental and social explanations have been proposed. One oft-repeated theory is tied to resource exploitation: specifically, that Native Americans ...

Scientists could be a step closer to finding a way to reduce the impact of traumatic memories, according to a Texas A&M University study published recently in the journal END ...

New Haven, Conn. -- Alzheimer's disease is known for its slow attack on neurons crucial to memory and cognition. But why are these particular neurons in aging brains so susceptible to the disease's ravages, while others remain resilient?

A new study led by researchers at the Yale School of Medicine has found that susceptible neurons in the prefrontal cortex develop a "leak" in calcium storage with advancing age, they report April 8 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia, The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. This disruption of calcium storage in turns ...

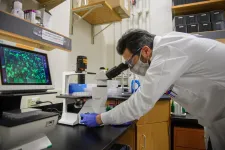

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New insights into the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infections could bring better treatments for COVID-19 cases.

An international team of researchers unexpectedly found that a biochemical pathway, known as the immune complement system, is triggered in lung cells by the virus, which might explain why the disease is so difficult to treat. The research is published this week in the journal Science Immunology.

The researchers propose that the pairing of antiviral drugs with drugs that inhibit this process may be more effective. Using an in vitro model using human lung ...

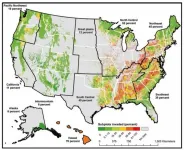

MADISON, WI, April 8, 2021 - USDA Forest Service scientists have delivered a new comprehensive assessment of the invasive species that confront America's forests and grasslands, from new arrivals to some that invaded so long ago that people are surprised to learn they are invasive.

The assessment, titled "Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector," serves as a one-stop resource for land managers who are looking for information on the invasive species that are already affecting the landscape, the species that may threaten the landscape, and what is known about control ...

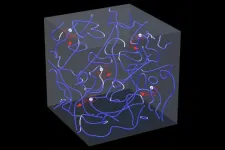

Nobel laureate in physics Richard Feynman once described turbulence as "the most important unsolved problem of classical physics."

Understanding turbulence in classical fluids like water and air is difficult partly because of the challenge in identifying the vortices swirling within those fluids. Locating vortex tubes and tracking their motion could greatly simplify the modeling of turbulence.

But that challenge is easier in quantum fluids, which exist at low enough temperatures that quantum mechanics -- which deals with physics on the scale of atoms or subatomic particles -- govern their behavior.

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Florida State University researchers ...

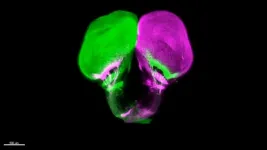

The network of nerves connecting our eyes to our brains is sophisticated and researchers have now shown that it evolved much earlier than previously thought, thanks to an unexpected source: the gar fish.

Michigan State University's Ingo Braasch has helped an international research team show that this connection scheme was already present in ancient fish at least 450 million years ago. That makes it about 100 million years older than previously believed.

"It's the first time for me that one of our publications literally changes the textbook that I am teaching with," said Braasch, as assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College ...

URBANA, Ill. - When scientists need to understand the effects of new infant formula ingredients on brain development, it's rarely possible for them to carry out initial safety studies with human subjects. After all, few parents are willing to hand over their newborns to test unproven ingredients.

Enter the domestic pig. Its brain and gut development are strikingly similar to human infants - much more so than traditional lab animals, rats and mice. And, like infants, young pigs can be scanned using clinically available equipment, including non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. That means researchers can test nutritional interventions in pigs, look at their effects on the developing brain via MRI, and make educated predictions about how those ...

Modern human-like brains evolved comparatively late in the genus Homo and long after the earliest humans first dispersed from Africa, according to a new study. By analyzing the impressions left behind by the ancient brains that once sat inside now fossilized skulls, the authors discovered that the brains of the earliest Homo retained a primitive, great ape-like organization of the frontal lobe. The findings challenge the long-standing assumption that human-like brain organization is a hallmark of early Homo and suggest that the evolutionary history of the human brain is more complex than previously thought. Our modern brains are larger and structurally different than those of our closest living relatives, ...

Researchers present a new, low-temperature method for injection-molding transparent fused silica glass, similar to how many plastic objects are manufactured. According to the authors, the process offers the possibility of producing complex and high-quality glass components using the same fabrication methods that allowed polymers to become one of the most important materials of the 21st century. The optical, thermal, mechanical and chemical properties of silicate glasses make them an ideal non-carbon based, high-performance material with applications ranging from packaging and architecture to high-throughput fiber optic ...