(Press-News.org) Detecting and analyzing breast cancer goes beyond the initial discovery of the cancer itself. If a patient has a tumor removed and it needs to be analyzed to determine further treatment, it might be OK for the results to take 24 hours. But if the patient is still on the operating table and clinicians are waiting to make sure no cancer cells are present along the edges of the removed tumor, results need to be nearly immediate.

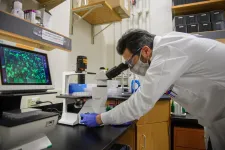

A paper titled, "Breast cancer histopathology using infrared spectroscopic imaging: The impact of instrumental configurations," was published in Clinical Spectroscopy, an extension of previous work by Beckman Institute Postdoctoral Fellow Shachi Mittal and Rohit Bhargava, bioengineering professor and director of the Cancer Center at Illinois. Two alumni of the Beckman Postdoctoral Fellows program, Michael Walsh and Tomasz Wrobel, are co-authors. It seeks to advance breast cancer detection methodologies when using spectroscopic imaging.

They conducted the research at the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign.

Because time is of the essence in breast cancer detection, the research identifies how clinicians can choose the right detection methods and tools during the correct scenario to still drive accurate results.

"The goal of the study was to give people a roadmap of how to plan and design an infrared imaging-based study for clinical work like digital histopathology," Mittal said. "In one scenario, you determine what instrument configuration will be better, and then you determine what types of methodologies you can use to develop accurate models with that instrument."

The team set out to examine the tradeoffs between using a standard Fourier transform infrared image or a high-definition Fourier transform infrared image.

"We wanted to see how the different types of instruments, especially different resolutions and how it impacts the capability of that data set to be used for different diagnostic purposes," Mittal said.

Instead of determining that one method is always superior, the researchers uncovered that the answer is much more complex. While high-definition imaging may seem like the best option regardless of the circumstances, sometimes standard definition infrared spectroscopy suffices in accuracy in instances when clinicians need a speedy result, for example.

"As technology expands and provides more capabilities with new features, it becomes more difficult to choose the optimal technology from the many options available," Bhargava said. "This study provides a nice comparison and guidelines to design a more useful and practical technology."

For Mittal, the research is an important step towards better dissecting, understanding, and curing cancer.

"Cancer is something we understand very little about," she said. "It's not only about the journey of battling the disease, but also the mental burden. Patients oftentimes don't understand, and they recognize the doctor may not fully understand either."

Mittal began her focus on breast cancer during her first graduate project, and continues to specialize her research in hopes to achieve something impactful that she can then apply to other types of cancers later in her academic career. She notes breast cancer has one of the highest mortality rates when looking at cancers that affect women.

"For females, it's not about just battling the disease, it also comes with a lot of cosmetic and life changing challenges," she said.

The interdisciplinary work that resulted in the paper was made possible by the Beckman Institute, Bhargava said.

"Developing new technology for human use requires a breadth of expertise that places like Beckman can bring together," he said. "I note that this study involves one current (Shachi) and one former (Tomasz) Beckman fellow as well as a Carle-Beckman Fellow (Michael). Together, these academicians' work is helping incubate a new community that provides chemical imaging technology to address human disease."

INFORMATION:

Many Mario Kart enthusiasts are familiar with the rush of racing down Rainbow Road, barely squeaking around a corner, and catching a power-up from one of the floating square icons on the screen--or, less ideally, slipping on a banana peel laid by another racer and flying off the side of the road into oblivion. This heated competition between multiple players, who use a variety of game tokens and tools to speed ahead or thwart their competitors, is part of what makes the classic Nintendo racing game that has been around since the early 1990s so appealing.

"It's been fun since I was a kid, it's fun ...

Whatever ultimately caused inhabitants to abandon Cahokia, it was not because they cut down too many trees, according to new research from Washington University in St. Louis.

Archaeologists from Arts & Sciences excavated around earthen mounds and analyzed sediment cores to test a persistent theory about the collapse of Cahokia, the pre-Columbian Native American city in southwestern Illinois that was once home to more than 15,000 people.

No one knows for sure why people left Cahokia, though many environmental and social explanations have been proposed. One oft-repeated theory is tied to resource exploitation: specifically, that Native Americans ...

Scientists could be a step closer to finding a way to reduce the impact of traumatic memories, according to a Texas A&M University study published recently in the journal END ...

New Haven, Conn. -- Alzheimer's disease is known for its slow attack on neurons crucial to memory and cognition. But why are these particular neurons in aging brains so susceptible to the disease's ravages, while others remain resilient?

A new study led by researchers at the Yale School of Medicine has found that susceptible neurons in the prefrontal cortex develop a "leak" in calcium storage with advancing age, they report April 8 in the journal Alzheimer's & Dementia, The Journal of the Alzheimer's Association. This disruption of calcium storage in turns ...

WEST LAFAYETTE, Ind. - New insights into the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 infections could bring better treatments for COVID-19 cases.

An international team of researchers unexpectedly found that a biochemical pathway, known as the immune complement system, is triggered in lung cells by the virus, which might explain why the disease is so difficult to treat. The research is published this week in the journal Science Immunology.

The researchers propose that the pairing of antiviral drugs with drugs that inhibit this process may be more effective. Using an in vitro model using human lung ...

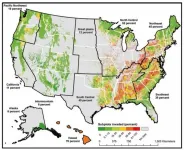

MADISON, WI, April 8, 2021 - USDA Forest Service scientists have delivered a new comprehensive assessment of the invasive species that confront America's forests and grasslands, from new arrivals to some that invaded so long ago that people are surprised to learn they are invasive.

The assessment, titled "Invasive Species in Forests and Rangelands of the United States: A Comprehensive Science Synthesis for the United States Forest Sector," serves as a one-stop resource for land managers who are looking for information on the invasive species that are already affecting the landscape, the species that may threaten the landscape, and what is known about control ...

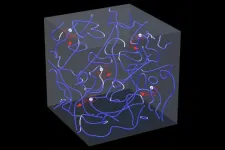

Nobel laureate in physics Richard Feynman once described turbulence as "the most important unsolved problem of classical physics."

Understanding turbulence in classical fluids like water and air is difficult partly because of the challenge in identifying the vortices swirling within those fluids. Locating vortex tubes and tracking their motion could greatly simplify the modeling of turbulence.

But that challenge is easier in quantum fluids, which exist at low enough temperatures that quantum mechanics -- which deals with physics on the scale of atoms or subatomic particles -- govern their behavior.

In a new study published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Florida State University researchers ...

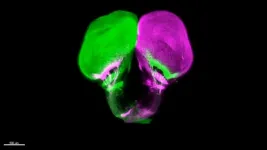

The network of nerves connecting our eyes to our brains is sophisticated and researchers have now shown that it evolved much earlier than previously thought, thanks to an unexpected source: the gar fish.

Michigan State University's Ingo Braasch has helped an international research team show that this connection scheme was already present in ancient fish at least 450 million years ago. That makes it about 100 million years older than previously believed.

"It's the first time for me that one of our publications literally changes the textbook that I am teaching with," said Braasch, as assistant professor in the Department of Integrative Biology in the College ...

URBANA, Ill. - When scientists need to understand the effects of new infant formula ingredients on brain development, it's rarely possible for them to carry out initial safety studies with human subjects. After all, few parents are willing to hand over their newborns to test unproven ingredients.

Enter the domestic pig. Its brain and gut development are strikingly similar to human infants - much more so than traditional lab animals, rats and mice. And, like infants, young pigs can be scanned using clinically available equipment, including non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging, or MRI. That means researchers can test nutritional interventions in pigs, look at their effects on the developing brain via MRI, and make educated predictions about how those ...

Modern human-like brains evolved comparatively late in the genus Homo and long after the earliest humans first dispersed from Africa, according to a new study. By analyzing the impressions left behind by the ancient brains that once sat inside now fossilized skulls, the authors discovered that the brains of the earliest Homo retained a primitive, great ape-like organization of the frontal lobe. The findings challenge the long-standing assumption that human-like brain organization is a hallmark of early Homo and suggest that the evolutionary history of the human brain is more complex than previously thought. Our modern brains are larger and structurally different than those of our closest living relatives, ...