INFORMATION:

This research was supported by the Cancer Institute NSW, the Cancer Council NSW, the National Breast Cancer Foundation and the National Health and Medical Research Council.

Inflammation a key to targeting pregnancy-associated breast cancer

2021-04-13

(Press-News.org) New research led by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research has revealed how breast cancer cells that develop during or after pregnancy change their environment to form more aggressive tumours.

In experimental models of pregnancy-associated breast cancer, researchers found that cancer cells send signals to the connective tissue around them to trigger uncontrolled inflammation and remodel the tissue, which in turn helps the cancer to spread.

"Breast cancers that arise during or shortly after pregnancy are highly aggressive as they often become resistant to standard therapies. With 50% of cases being fatal, better treatment options are urgently needed," says Dr David Gallego-Ortega, Leader of the Tumour Development Group at Garvan and co-senior author of the new study published in Cell Reports.

"Our study has revealed a crosstalk between these breast cancer cells and their environment that is fuelling the right conditions for cancer to metastasise, and reveals the inflammation itself as a potential new therapeutic target for the disease."

Breast cancer during pregnancy

While a breast cancer diagnosis is devastating for any patient, the prognosis is far worse for pregnant women and new mothers. One in every two women diagnosed with pregnancy-associated breast cancer, which affects up to 40 of every 100,000 women giving birth, will lose their battle within five years of diagnosis.

"Breast cancer survival rates reduce from 80% to just 52% for young mothers who develop breast cancer while pregnant," says co-first author Dr Fatima Valdes-Mora from the Children's Cancer Institute, who conducted the research at the Garvan Institute.

"We set out to understand the cellular basis of how pregnancy triggers a more aggressive breast cancer and how current treatment could be improved."

Using next-generation cellular genomics technology, the researchers analysed a snapshot of gene activity of the individual cells found within the tumours of an experimental model of pregnancy-associated breast cancer. Interestingly, the researchers observed a number of changes not just in the cancer cells themselves, but in the surrounding connective tissue cells.

An environment for cancer to thrive

"In normal breast tissue cells, when mothers stop breastfeeding, changes in hormonal signals tell the connective tissue around milk-producing cells to revert to its pre-pregnancy form. But we found when similar signals were sent by breast cancer cells, they triggered changes that enabled inflammation and faster cancer spread," says Dr Gallego-Ortega.

"The genomic data showed us that as they received pregnancy cues, breast cancer cells transitioned to the more malignant 'basal' breast cancer subtype. At the same time, the cells were 'tweaking' their environment, signalling to cells around them to turn on inflammation within the tumour tissue."

In their model, the researchers found that cells in the tumour environment drove changes that make pregnancy-associated breast cancer highly aggressive - uncontrolled inflammation, tissue remodelling and the generation of new blood vessels.

Path to improving therapy

The findings have prompted the researchers to explore new therapeutic targets for pregnancy-associated breast cancer. In experimental models, the team is next aiming to test whether treating the inflammatory pathways in the tumour environment - some of which can be targeted with existing medication such as ibuprofen - could reduce the spread of pregnancy-associated breast cancers and improve outcomes of current treatments.

"Pregnancy can provide cancers with a route of escape from therapy and from their location in the breast," explains Prof Chris Ormandy, co-senior author and Head of the Cancer Biology Lab at Garvan. "Our study suggests that targeting inflammation is one way to stay a step ahead of the disease."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Huntington's Disease: Neural traffic could help understand the disease

2021-04-13

Huntington's disease is a genetic neurodegenerative disorder caused by mutations in the protein huntingtin and characterized by involuntary dance-like movements, severe behavioural changes and cognitive impairment. That neuronal traffic is impaired in this disease has been very well known for several years. But that this deranged trafficking could be ameliorated by increasing huntingtin methylation was not yet known. The findings emerged from an international research work coordinated by the University of Trento and published in Cell Reports.

The research teams identified the fundamental role of the protein arginine methyltransferase PRMT6 in ensuring transport along axons, the routes that connect nerve cells to each other, and hence the health of neurons. ...

First patient-derived organoid model for cervical cancer

2021-04-13

Researchers from the group of Hans Clevers (Hubrecht Institute) developed the first patient-derived organoid model for cervical cancer. They also modelled the healthy human cervix using organoids. In close collaboration with the UMC Utrecht, Princess Máxima Center for pediatric oncology and the Netherlands Cancer Institute, the researchers used the organoid-based platform to study sexually transmitted infections for a herpes virus. The model can potentially also be used to study the human papillomavirus (HPV), which is one of the main causes of cervical cancer. The results were published in Cell Stem Cell on the 13th of April.

Cervical cancer is a common gynecological malignancy, often caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). However, good models to study human ...

Study provides novel platform to study how SaRS-CoV-2 affects the gut

2021-04-13

(Boston)--How could studying gastrointestinal cells help the fight against COVD-19, which is a respiratory disease? According to a team led by Gustavo Mostoslavsky, MD, PhD, at the BU/BMC Center for Regenerative Medicine (CReM) and Elke Mühlberger, PhD, from the National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories (NEIDL) at Boston University, testing how SARS-CoV-2 affects the gut can potentially serve to test novel therapeutics for COVID-19.

In order to study SARS-CoV-2, models are needed that can duplicate disease development in humans, identify potential targets and enable drug testing. BU researchers have created human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC)-derived intestinal organoids or 3-D models that can be infected and replicated ...

DNA structure itself is involved in genome regulation

2021-04-13

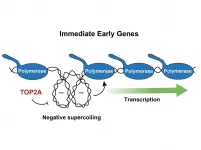

The (when stretched) two-metre-long DNA molecule in each human cell is continuously being unpacked and packed again to enable the expression of genetic information. When genes must be accessed for transcription, the DNA double helix unwinds and the strands separate from each other so that all the elements needed for gene expression can access the relevant DNA region. This process results in the accumulation of DNA supercoiling that needs to be resolved. A study recently published by Felipe Cortés, Head of the Topology and DNA Breaks Group at the Spanish National Cancer Research Centre (CNIO), and the members of his team, in cooperation with Silvia Jimeno González, Professor ...

Scaling up genome editing big in tiny worms

2021-04-13

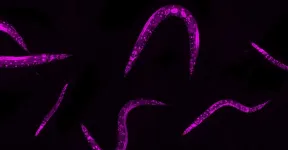

Understanding the effects of specific mutations in gene regulatory regions - the sections of DNA and RNA that turn genes on and off - is important to unraveling how the genome works, as well as normal development and disease. But studying a large variety of mutations in these regulatory regions in a systematic way is a monumental task. While progress has been made in cell lines and yeast, few studies in live animals have been done, especially in large populations.

Experimental and computational biologists at the Max Delbrück Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC) have teamed up to establish an approach to induce thousands of different mutations in up to 1 million ...

The role of hydrophobic molecules in catalytic reactions

2021-04-13

Electrochemical processes could be used to convert CO2 into useful starting materials for industry. To optimise the processes, chemists are attempting to calculate in detail the energy costs caused by the various reaction partners and steps. Researchers from Ruhr-Universität Bochum (RUB) and Sorbonne Université in Paris have discovered how small hydrophobic molecules, such as CO2, contribute to the energy costs of such reactions by analysing how the molecules interact in water at the interface. The team describes the results in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, PNAS for short, published online on 13 April 2021.

To conduct the ...

The amount of time children spend watching screens influences their eating habits

2021-04-13

The time children and adolescents spend on screen time entertainment -computers, mobile phones, television and video games- adversely affects their eating habits. This is the main conclusion drawn from a research carried out by EpiPHAAN (Epidemiology, Physical Activity, Accelerometry and Nutrition) research group of the University of Malaga, which further establishes that parents' education level is also associated with the adherence to the Mediterranean diet.

This research was conducted within the PASOS Study -Physical Activity, Sedentarism, lifestyles and Obesity in Spanish youth- of Gasol Foundation, which analyzed more than ...

UK cancer patients more likely to die following COVID-19 than European cancer patients

2021-04-13

Cancer patients from the UK were 1.5 times more likely to die following a diagnosis with COVID-19 than cancer patients from European countries.

This is the finding of a study of over 1000 patients - 924 from European countries and 468 from the UK - during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. The research team, led by Imperial College London, say the study highlights the need for UK cancer patients to be prioritised for vaccination.

The study tracked data between 27 February to 10 September 2020, across 27 centres in six countries: Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, Germany and the UK.

The results, published in the European Journal of Cancer, showed that 30 days after a COVID-19 diagnosis, 40.38 per cent of UK cancer patients had died, versus 26.5 per cent of ...

Machine learning can help slow down future pandemics

2021-04-13

Artificial intelligence could be one of the keys for limiting the spread of infection in future pandemics. In a new study, researchers at the University of Gothenburg have investigated how machine learning can be used to find effective testing methods during epidemic outbreaks, thereby helping to better control the outbreaks.

In the study, the researchers developed a method to improve testing strategies during epidemic outbreaks and with relatively limited information be able to predict which individuals offer the best potential for testing.

"This can be a first step towards society ...

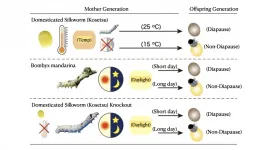

Silk moth's diapause reverts back to ancestors' through gene editing!?

2021-04-13

Diapause is a phenomenon in which animals and insects foresee changes in the environment and actively reduce metabolism, or halt regular differentiation and development. It is an adaptation strategy for adverse environments such as surviving winters, but also to encourage uniform growth of the generational group. By knocking out genes that allow the silkworm to detect temperature, researchers at Shinshu University et al. found that the silk moth diapause changes from temperature to photoperiod, or day length. This is not only valuable as an elucidation of the molecular mechanism in the environmental response mechanism of organisms such as insects, but also a very important finding in exploring the process of domestication of silk ...