(Press-News.org) Like tree rings, cave stalagmites are a portal to a prehistoric Earth, and now scientists from UNSW Sydney have found they are consistently reliable as time trackers the world over.

In a global investigation into the growth properties of stalagmites distributed across the world, the scientists found that while growth fluctuations due to climate events are evident in the shorter period, stalagmite growth over the longer periods - tens of thousands of years - are surprisingly linear.

"Our new global analysis shows that we can consider stalagmite growth as being like a metronome and very constant over hundreds and thousands of years," says Professor Andy Baker, UNSW School of Biological, Earth and Environmental Sciences.

"Sometimes extreme weather events can disturb this metronome for a few years, making the growth a bit faster or slower, and we can use that to explore climate variations.

"But in general, stalagmite growth is predictable and it is this unique property that makes them so valuable to researchers - you can tell the time in the past by using the very regular growth rings that are widely present across the globe."

Stalagmites, which grow from cave floors as water drips from stalactites at the cave ceiling, are the result of chemicals carried by the water in solution that turns to solid form in the cave. They are built by layers of calcite crystals, which may be perfectly stacked one on top of the other if nothing disturbs the growth.

"But in reality, there are many disturbances in caves," says Prof. Baker.

"Tiny particles from the soil above and trace elements of chemicals can disturb the stacking to create pores between growing crystals or even slightly change their shape in the morphology - or fabric - of the growing crystals."

STEADY GROWTH

Scientists have used stalagmites as gauges of different parts of the planet's conditions over millennia for some time, but whether all stalagmites grew the same way in caves of different climatic conditions remained unknown - until now.

"Before this analysis, we did not have evidence that stalagmites are only found in regions with seasonal precipitation, nor was it obvious that the stalagmite growth rate is relatively unchanging over time and that this is a ubiquitous property," Prof. Baker says.

"What we have learned is that for an environmental signal to be preserved in stalagmite laminae thickness variations, a large perturbation to weather patterns is required - such as prolonged wet or dry years associated El Niño or La Niña.

"But in regions where there is a seasonality of precipitation, the long-term constant growth rate of laminated stalagmites provides an unparalleled capacity for precise chronology building."

The researchers found that between different locations around the world, warmer climates tended towards more stalagmite growth over time, while colder climates saw growth slowed.

But the research showed that the majority of stalagmite samples, irrespective of location, followed a linear growth over the timescale of tens of thousands of years.

"The 'global average stalagmite' increased in height by about one metre over the last 11,000 years," Prof. Baker says.

SNAPSHOT OF THE PAST

Analysing the way the laminae are organised can help scientists read environmental conditions and weather events of the distant past. In seasonal climates, these changes in the fabric can occur at regular intervals, producing layers they call 'annually laminated stalagmites'. But when extreme weather events occur, as happens with the El Niño/La Niña Southern Oscillation phenomenon involving mega-droughts, bushfires and flooding events, variations of thicknesses of stalagmite laminae can provide vital clues.

"We can use other chemical evidence in stalagmites to obtain records of past environmental change, and know exactly when this happened," says Prof. Baker.

"For example, at UNSW we are reconstructing fire histories from cave stalagmites for the first time. Working in Western Australia, and using stalagmites that have these continuous laminae and regular growth, we can identify how often fires have occurred in the past from the traces left behind from the soluble part of bushfire ash that gets transported to the stalagmite by drip water."

The researchers say that they still have limited understanding on how crystals grow within each lamina, so future studies could investigate the internal structure of the laminae and the crystal growth mechanisms involved.

The analysis was published in the April issue of Reviews of Geophysics journal.

INFORMATION:

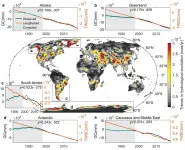

WASHINGTON-- Glacial melting due to global warming is likely the cause of a shift in the movement of the poles that occurred in the 1990s.

The locations of the North and South poles aren't static, unchanging spots on our planet. The axis Earth spins around--or more specifically the surface that invisible line emerges from--is always moving due to processes scientists don't completely understand. The way water is distributed on Earth's surface is one factor that drives the drift.

Melting glaciers redistributed enough water to cause the direction of polar wander to turn and accelerate eastward during the mid-1990s, according to a new study in Geophysical Research Letters, AGU's journal for high-impact, ...

CHAMPAIGN, Ill. -- Attempts at restricting people's mobility to control the spread of COVID-19 may be effective only for a short period, researchers said. A new study examines people's mobility for seven months during the pandemic in the United States using publicly available, anonymized mobile phone data.

Reported in the Journal of Transport Geography, the study alerts authorities to the need for more manageable travel restrictions and policies that reduce COVID-19 exposure risk to essential workers - who, because they are required to be physically present at their workplaces, remained highly mobile during the pandemic.

The longitudinal study is one of the first to compare mobility data using a broad ...

Being unable to walk quickly can be frustrating and problematic, but it is a common issue, especially as people age. Noting the pervasiveness of slower-than-desired walking, engineers at Stanford University have tested how well a prototype exoskeleton system they have developed - which attaches around the shin and into a running shoe - increased the self-selected walking speed of people in an experimental setting.

The exoskeleton is externally powered by motors and controlled by an algorithm. When the researchers optimized it for speed, participants walked, on average, 42 percent faster than when they were wearing normal shoes and no exoskeleton. The results of this study were ...

Young scientists of Tomsk Polytechnic University as a part of the team of Arctic researchers have studied pore waters in three areas of methane release on the surface. They first managed to define in details the composition of pore waters in the cold methane seeps of the Eastern Arctic seas. The research findings are published in the Water academic journal.

The research was based on the samples obtained during the Arctic expedition aboard the research vessel "Akademik Mstislav Keldysh" in 2019. The scientists and students from 12 scientific institutions, including Tomsk Polytechnic University, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, the Research Center of Biotechnology ...

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) largely remedies Superfund sites containing asbestos by capping them with soil to lock the buried toxin in place. But new research suggests that this may actually increase the likelihood of human exposure to the cancer-causing mineral.

"People have this idea that asbestos is all covered up and taken care of," said Jane Willenbring, who is an associate professor of geological sciences at Stanford University's School of Earth, Energy & Environmental Sciences (Stanford Earth). "But this is still a lingering legacy pollutant ...

Sugar is not just something we eat. On the contrary. Sugar is one of the most naturally occurring molecules, and all cells in the body are covered by a thick layer of sugar that protects the cells from bacteria and virus attacks. In fact, close to 80 per cent of all viruses and bacteria bind to the sugars on the outside of our cells.

Sugar is such an important element that scientists refer to it as the third building block of life - after DNA and protein. And last autumn, a group of researchers found that the spike protein in corona virus needs a particular sugar to bind to our cells efficiently.

Now the same group of researchers have completed a new study that further digs into the cell receptors to which sugars and thus bacteria and virus ...

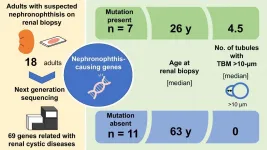

Researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) in a pioneering study identify clinical, genetic and histopathological characteristics that may help confirm the diagnosis when nephronophthisis occurs in adults

Tokyo, Japan - Nephronophthisis (NPH) is a kidney disease affecting mainly children. Now, for the first time, researchers at Tokyo Medical and Dental University (TMDU) have studied a number of adults with NPH and highlighted clinical, genetic and pathological characteristics that could help in confirming this challenging diagnosis.

NPH is inherited in an autosomal recessive pattern and, though rare, is the commonest genetic cause of kidney failure in children. The ...

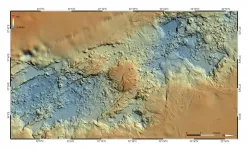

It is 2,250 kilometers long, but only 355 kilometers wide at its widest point - on a world map, the Red Sea hardly resembles an ocean. But this is deceptive. A new, albeit still narrow, ocean basin is actually forming between Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Exactly how young it is and whether it can really be compared with other young oceans in Earth's history has been a matter of dispute in the geosciences for decades. The problem is that the newly formed oceanic crust along the narrow, north-south aligned rift is widely buried under a thick blanket of salt and sediments. This complicates direct investigations.

In the international journal Nature Communications, scientists from GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research Kiel, ...

Tsukuba, Japan - Blood vessels can be injured by the build-up of atherosclerosis and long-standing hypertension, among other conditions. As a consequence, blood vessels may undergo a process called remodeling, whereby their walls thicken and cause blockages (known as occlusion). In a new study, researchers from the University of Tsukuba discovered how cells marked by platelet-derived growth factor receptor alpha (PDGFRa+) residing predominantly in the most outer layer of blood vessels contribute to their remodeling.

Blood vessels comprise three layers, each of which fulfills a unique role ...

Single-molecule fluorescence detection (SMFD) is able to probe, one molecule at a time, dynamical processes that are crucial for understanding functional mechanisms in biosystems. Fluorescence in the Near-infrared (NIR) offers improved Signal to Noise Ratio (SNR) by reducing the scattering, absorption and autofluorescence from biological cellular or tissue samples, therefore, provides high imaging resolution with increased tissue penetration depth that are important for biomedical applications. However, most NIR-emitters suffer from low quantum yield, the weak NIR fluorescence signal makes the detection extremely difficult.

Plasmonic nanostructures are capable of converting localized electromagnetic energy into free radiation ...