(Press-News.org) MADISON, Wis. -- In October of 2020, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their discovery of an adaptable, easy way to edit genomes, known as CRISPR, which has transformed the world of genetic engineering.

CRISPR has been used to fight lung cancer and correct the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia in stem cells. But the technology was also used by a Chinese scientist to secretly and illegally edit the genomes of twin girls -- the first-ever heritable mutation of the human germline made with genetic engineering.

"We've moved away from an era of science where we understood the risks that came with new technology and where decision stakes were fairly low," says Dietram Scheufele, a professor of life sciences communication at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Today, Scheufele and his colleagues say, we're in a world where new technologies have very immediate and sometimes unpredictable but significant impacts on society. In a paper published the week of April 26 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers argue that such advanced tech, especially CRISPR, demands more robust and thoughtful public engagement if it is to be harnessed to benefit the public without crossing ethical lines.

The authors say that being thoughtful and transparent about public engagement goals and using evidence from social science can help facilitate the difficult conversations society must have about scientific issues like CRISPR and their societal implications. Effective public engagement, in turn, lays the groundwork for public ownership of advances that do arise from CRISPR.

Life sciences communication Professor Dominique Brossard and graduate student Nicole Krause, along with University of Vienna research assistant Isabelle Freiling, co-authored the report with Scheufele. The paper stems from a 2019 National Academy of Sciences colloquium on CRISPR.

Since 2012, when the CRISPR system was first described, scientists have understood both its genetic engineering potential and the need for public engagement to discuss the possible uses of the technology. Many scientists wanted to avoid rehashing the controversies surrounding genetically modified organisms, which have been harshly criticized as unnatural and unnecessary by some activists despite broad scientific support for their use.

Yet, Krause says, some scientists who supported using CRISPR began by errantly repeating the public engagement methods employed for GMOs, which "assumes that people just need more knowledge, more of an ability to understand the science." Instead, Krause adds: "Solutions focused on tailoring communications to people's values would make more sense."

This values-based public engagement strategy is supported by social science research into how people form and change their opinions around new technologies. Some public engagement methods engage value systems, and encourage thoughtful conversation, more than others.

For example, what researchers term "public involvement" and "public collaboration" are methods of two-way communication involving the joint exchange of information and values and the identification and design of science-based decisions that adhere to those values. That contrasts with "public communication," which focuses only on the dissemination of scientific information.

Scheufele and his colleagues say that such collaborative approaches could help scientists widen the representation of voices in debates around science to groups who are often overlooked, such as people with disabilities or racial minorities.

"As the scientific community, we don't have a long track record of effective engagement mechanism with these communities," says Scheufele. This failure to reach broader groups stems in part from the low participation rates of most science engagement events, which also attract highly selective audiences.

Another challenge is rewarding scientists for public engagement. "There's very little incentive in academia to do this kind of work," says Scheufele.

A recent report by Brossard and others found that a majority of land-grant faculty felt that public engagement was very important, but believed it was less important to their colleagues. That divide suggests scientists feel their engagement efforts won't be rewarded by their peers, says Brossard.

Now, Brossard, Krause, Scheufele and colleagues have a grant from the National Science Foundation to research how to depolarize debates around CRISPR. Previous studies suggest that making people accountable for their positions helps them think more critically about their underlying reasoning. And when social scientists emphasize the complexity inherent in people's values, it helps people consider controversial issues with more nuance.

But engaging a diverse society with pluralistic value systems in deliberations on the latest technologies will never be easy.

"The policymaking process involves a lot more than just science. Science will inform how we regulate technologies, and so will religious, political, ethical, regulatory and economic considerations," says Scheufele. "And so the ability to actually do engagement in this much broader setting where we meaningfully contribute and guide the debate with the best available science is a major challenge."

INFORMATION:

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (grant SES-1827864).

Eric Hamilton, (608) 263-1986, eshamilton@wisc.edu

New findings detailing the world's first-of-its-kind estimate of how many people live in high-altitude regions, will provide insight into future research of human physiology.

Dr. Joshua Tremblay, a postdoctoral fellow in UBC Okanagan's School of Health and Exercise Sciences, has released updated population estimates of how many people in the world live at a high altitude.

Historically the estimated number of people living at these elevations has varied widely. That's partially, he explains, because the definition of "high altitude" does not have a fixed cut-off.

Using novel techniques, Dr. Tremblay's publication in the Proceedings of the National ...

New research reveals a genetic quirk in a small species of songbird in addition to its ability to carry a tune. It turns out the zebra finch is a surprisingly healthy bird.

A study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that zebra finches and other songbirds have a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene surprisingly different than other vertebrates.

The function of LDLR, which is responsible for cellular uptake of LDL-bound cholesterol, or "bad cholesterol," has been thought to be conserved across vertebrates. OHSU scientists found that in the case ...

Stomata, formed by a pair of kidney-shaped guard cells, are tiny pores in leaves. They act like mouths that plants use to "eat" and "breathe." When they open, carbon dioxide (CO2) enters the plant for photosynthesis and oxygen (O2) is released into the atmosphere. At the same time as gases pass in and out, a great deal of water also evaporates through the same pores by way of transpiration.

These "mouths" close in response to environmental stimuli such as high CO2 levels, ozone, drought and microbe invasion. The protein responsible for closing these "mouths" is an anion channel, called SLAC1, which moves negatively charged ions across the guard cell membrane to reduce turgor pressure. Low pressure causes the guard cells to collapse and subsequently the stomatal pore to ...

(Boston)--Lung carcinomas are the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and worldwide. Lung squamous cell carcinomas (non-small cell lung cancers that arise in the bronchi of the lungs and make up approximately 30 percent of all lung cancers) are poorly understood, particularly with respect to the cell type and signals that contribute to disease onset.

According to the researchers, treatments for lung squamous cell carcinomas are limited and research into the etiology of the disease is required to create new ways to treat it.

"Our study offers insight into how damage ...

A multi-institutional team of researchers has identified both the genetic abnormalities that drive pre-cancer cells into becoming an invasive type of head and neck cancer and patients who are least likely to respond to immunotherapy.

"Through a series of surprises, we followed clues that focused more and more tightly on specific genetic imbalances and their role in the effects of specific immune components in tumor development," said co-principal investigator Webster Cavenee, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

"The genetic ...

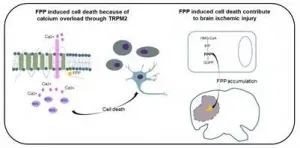

A vital intermediate in normal cell metabolism is also, in the right context, a trigger for cell death, according to a new study from Wanli Liu and Yonghui Zhang of Tsinghua University, and Yong Zhang of Peking University in Beijing, publishing 26th April 2021 in the open access journal PLOS biology. The discovery may contribute to a better understanding of the damage caused by stroke, and may offer a new drug target to reduce that damage.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) is an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, a series of biochemical reactions in every cell that contributes to protein synthesis, energy production, and construction of cell membranes. During a search for regulators of immune cell function, the authors unexpectedly discovered that FPP, when present at high concentrations ...

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be at risk of developing heart failure even if they do not have a previous history of heart disease or cardiovascular risk factors, a new Mount Sinai study shows.

Researchers say that while these instances are rare, doctors should be aware of this potential complication. The study, published in the April 26 online issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, may prompt more monitoring of heart failure symptoms among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

"This is one of the largest studies to date to specifically capture instances of new heart failure diagnosis among patients hospitalized ...

Skid marks left by cars are often analyzed for their impression patterns, but they often don't provide enough information to identify a specific vehicle. UCF Chemistry Associate Professor Matthieu Baudelet and his forensics team at the National Center for Forensic Science, which was established at UCF in 1997, may have just unlocked a new way to collect evidence from those skid marks.

The team recently published a study in the journal Applied Spectroscopy that details how they are classifying the chemical profile of tires to link vehicles back to potential crime ...

A genome by itself is like a recipe without a chef - full of important information, but in need of interpretation. So, even though we have sequenced genomes of our nearest extinct relatives - the Neanderthals and the Denisovans - there remain many unknowns regarding how differences in our genomes actually lead to differences in physical traits.

"When we're looking at archaic genomes, we don't have all the layers and marks that we usually have in samples from present-day individuals that help us interpret regulation in the genome, like RNA or cell structure," said David Gokhman, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at Stanford University.

"We ...

Gossip is often considered socially taboo and dismissed for its negative tone, but a Dartmouth study illustrates some of its merits. Gossip facilitates social connection and enables learning about the world indirectly through other people's experiences.

Gossip is not necessarily spreading rumors or saying bad things about other people but can include small talk in-person or online, such as having a private chat during a Zoom meeting. Prior research has found that approximately 14% of people's daily conversations are gossip, and primarily neutral in tone.

"Gossip is ...