(Press-News.org) Understanding spoken words, developing normal speech - cochlear implants enable people with profound hearing impairment to gain a great deal in terms of quality of life. However, background noises are problematic, they significantly compromise the comprehension of speech of people with cochlear implants. The team led by Tobias Moser from the Institute for Auditory Neuroscience and InnerEarLab at the University Medical Center Göttingen and from the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory at the German Primate Center - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research (DPZ) is therefore working to improve cochlear implants. The scientists want to use genetic engineering methods to make the nerve cells in the ear sensitive to light so that they can then be stimulated with light instead of electricity, as is currently the case. By using light, the scientists expect, to be able to stimulate the neurons in the ear more selectively. Now the team has succeeded in taking another important step toward developing the optical cochlear implant. In collaboration with a team of X-ray physicists led by Tim Salditt, who, like Moser, also conducts research at the Cluster of Excellence Multiscale Bioimaging (MBExC) Göttingen, they were able to use combined imaging techniques of X-ray tomography and fluorescence microscopy to create detailed images of the cochleae of rodents and non-human primates. This determined important parameters for the design and material consistence of optical cochlear implants. In addition, the researchers, who include scientists from the Collaborative Research Center 889, succeeded in simulating the propagation of light in the cochlea of the common marmoset. The results of the simulation show that spatially limited optogenetic stimulation of auditory neurons is possible. Accordingly, optical stimulation would lead to a much more differentiated auditory impression than the electrical stimulation used so far. The results of the study were published in the scientific journal PNAS.

430 million people, more than 5 percent of the world's population, are affected by hearing loss and deafness, according to current World Health Organization (WHO) estimates. The causes are many: genetic factors, infections, chronic diseases, trauma to the ear or head, loud sounds and noise, but also side effects of medications. Hearing aids and electric cochlear implants remain the most commonly used devices to rehabilitate hearing loss, the latter being worn by more than 700,000 people worldwide. The electrical cochlea implants allow otherwise profoundly deaf or hard of hearing users to understand speech in absence of nonverbal cues, for example on the telephone. However, background noise significantly impairs this understanding. Even linguistic subtleties that speakers convey by changing the pitch or melody of speech cannot be picked up by conventional implants. This is mainly due to poor frequency and intensity resolution. Electrical cochlear implants stimulate nerve cells in the ear by means of an electrical current transmitted from 12 to 24 electrodes. However, the current distributes widely in the fluid of the cochlea, which affects hearing quality. Since light can be focused, the optogenetic stimulation of auditory neurons envisioned by Tobias Moser's team promises to significantly improve frequency and intensity resolution.

The development of optical cochlear implants is a complex undertaking that involves many researchers from different disciplines, from research in basic principles to clinical applications. One factor is the complicated structure of the cochlea, which is poorly accessible for investigation, even by imaging because it is deeply embedded in the temporal bone. However, detailed knowledge of the structure of the cochlea is critical for the development of innovative therapy of deafness. Researchers rely on animal studies to develop the gene therapy and optical cochlear implants and to test their efficacy and safety. Suitable animal models include rodents such as mouse, rat, gerbil, and as research progresses, non-human primates. At DPZ, the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory conducts research with common marmosets, whose behavior in vocal communication is similar to that of humans. "For (late) preclinical studies, detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the cochlea is necessary. We used phase-contrast X-ray tomography and light sheet fluorescence microscopy, as well as a combination of the two, to image the structure of the cochlea of both major rodent models and common marmosets," explained Daniel Keppeler, first author of the study. "For cross-scale and multimodal imaging, we developed special instruments and methods, both here in our lab and with synchrotron radiation," adds collaborating partner Tim Salditt, professor at the Institute of X-ray Physics at the University of Göttingen, who led the research team in X-ray tomography. "In this way, we were able to gain detailed insights into the anatomy of bones, tissues and nerve cells. These parameters are relevant for the development of implants specifically for these species," says Daniel Keppeler.

With the data obtained on the anatomy of the different cochleae, the team was also able to design an implant with LED emitters for common marmosets and the implant was then inserted by Alexander Meyer, an experienced ear, nose and throat surgeon, at the University Medical Center Göttingen in a manner analogous to surgery in humans.

Furthermore, the researchers used imaging data to simulate the propagation of light generated by the emitters of the optical implants in the cochlea of non-human primates. "Our simulations indicate spatially limited optogenetic excitation of auditory neurons and thus higher frequency selectivity than with previous electrical stimulation. According to these calculations, optical cochlear implants lead to significantly improved hearing of speech as well as of music," concludes Tobias Moser, senior author of the study.

INFORMATION:

The study was conducted in cooperation between researchers from the German Primate Center - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research with the Cluster of Excellence Multiscale Bioimaging: From Molecular Machines to Networks of Excitable Cells (MBExC) and the Collaborative Research Center "Cellular Mechanisms of Sensory Processing" (SFB889) at the University Medical Center Göttingen, the University of Göttingen, and the Max-Planck-Institute for Experimental Medicine.

Original publication

Keppeler D, Kampshoff C, Thirumalai A, Duque-Afonso CJ, Schaeper J, Quilitz T, Töpperwien M, Vogl C, Hessler R, Meyer A, Salditt T, Moser T (2021) Multiscale photonic imaging of the native and implanted cochlea. PNAS. https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2014472118

The German Primate Center GmbH (DPZ) - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research conducts biological and biomedical research on and with primates in the fields of infection research, neuroscience and primate biology. The DPZ also maintains four field stations in the tropics and is a reference and service center for all aspects of primate research. The DPZ is one of the 96 research and infrastructure facilities of the Leibniz Association.

The Göttingen Cluster of Excellence 2067 Multiscale Bioimaging: From Molecular Machines to Networks of Excitable Cells (MBExC) is funded within the Excellence Strategy of the German Federal Government and the Länder (federals states) since January 2019. With a unique interdisciplinary research approach, MBExC investigates the disease-relevant functional units of electrically active heart and nerve cells, from the molecular to the organ level. For this purpose, MBExC unites numerous university and non-university partners at the Göttingen Campus. The overarching goal: to understand the connection between heart and brain diseases, to link basic and clinical research, and thus to develop new therapeutic and diagnostic approaches with societal implications.

MADISON, Wis. -- In October of 2020, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their discovery of an adaptable, easy way to edit genomes, known as CRISPR, which has transformed the world of genetic engineering.

CRISPR has been used to fight lung cancer and correct the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia in stem cells. But the technology was also used by a Chinese scientist to secretly and illegally edit the genomes of twin girls -- the first-ever heritable mutation of the human germline made with genetic engineering.

"We've moved away from an era of science where we understood the risks that came with new technology and where decision stakes were ...

New findings detailing the world's first-of-its-kind estimate of how many people live in high-altitude regions, will provide insight into future research of human physiology.

Dr. Joshua Tremblay, a postdoctoral fellow in UBC Okanagan's School of Health and Exercise Sciences, has released updated population estimates of how many people in the world live at a high altitude.

Historically the estimated number of people living at these elevations has varied widely. That's partially, he explains, because the definition of "high altitude" does not have a fixed cut-off.

Using novel techniques, Dr. Tremblay's publication in the Proceedings of the National ...

New research reveals a genetic quirk in a small species of songbird in addition to its ability to carry a tune. It turns out the zebra finch is a surprisingly healthy bird.

A study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that zebra finches and other songbirds have a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene surprisingly different than other vertebrates.

The function of LDLR, which is responsible for cellular uptake of LDL-bound cholesterol, or "bad cholesterol," has been thought to be conserved across vertebrates. OHSU scientists found that in the case ...

Stomata, formed by a pair of kidney-shaped guard cells, are tiny pores in leaves. They act like mouths that plants use to "eat" and "breathe." When they open, carbon dioxide (CO2) enters the plant for photosynthesis and oxygen (O2) is released into the atmosphere. At the same time as gases pass in and out, a great deal of water also evaporates through the same pores by way of transpiration.

These "mouths" close in response to environmental stimuli such as high CO2 levels, ozone, drought and microbe invasion. The protein responsible for closing these "mouths" is an anion channel, called SLAC1, which moves negatively charged ions across the guard cell membrane to reduce turgor pressure. Low pressure causes the guard cells to collapse and subsequently the stomatal pore to ...

(Boston)--Lung carcinomas are the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and worldwide. Lung squamous cell carcinomas (non-small cell lung cancers that arise in the bronchi of the lungs and make up approximately 30 percent of all lung cancers) are poorly understood, particularly with respect to the cell type and signals that contribute to disease onset.

According to the researchers, treatments for lung squamous cell carcinomas are limited and research into the etiology of the disease is required to create new ways to treat it.

"Our study offers insight into how damage ...

A multi-institutional team of researchers has identified both the genetic abnormalities that drive pre-cancer cells into becoming an invasive type of head and neck cancer and patients who are least likely to respond to immunotherapy.

"Through a series of surprises, we followed clues that focused more and more tightly on specific genetic imbalances and their role in the effects of specific immune components in tumor development," said co-principal investigator Webster Cavenee, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

"The genetic ...

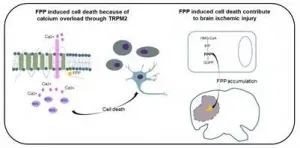

A vital intermediate in normal cell metabolism is also, in the right context, a trigger for cell death, according to a new study from Wanli Liu and Yonghui Zhang of Tsinghua University, and Yong Zhang of Peking University in Beijing, publishing 26th April 2021 in the open access journal PLOS biology. The discovery may contribute to a better understanding of the damage caused by stroke, and may offer a new drug target to reduce that damage.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) is an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, a series of biochemical reactions in every cell that contributes to protein synthesis, energy production, and construction of cell membranes. During a search for regulators of immune cell function, the authors unexpectedly discovered that FPP, when present at high concentrations ...

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be at risk of developing heart failure even if they do not have a previous history of heart disease or cardiovascular risk factors, a new Mount Sinai study shows.

Researchers say that while these instances are rare, doctors should be aware of this potential complication. The study, published in the April 26 online issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, may prompt more monitoring of heart failure symptoms among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

"This is one of the largest studies to date to specifically capture instances of new heart failure diagnosis among patients hospitalized ...

Skid marks left by cars are often analyzed for their impression patterns, but they often don't provide enough information to identify a specific vehicle. UCF Chemistry Associate Professor Matthieu Baudelet and his forensics team at the National Center for Forensic Science, which was established at UCF in 1997, may have just unlocked a new way to collect evidence from those skid marks.

The team recently published a study in the journal Applied Spectroscopy that details how they are classifying the chemical profile of tires to link vehicles back to potential crime ...

A genome by itself is like a recipe without a chef - full of important information, but in need of interpretation. So, even though we have sequenced genomes of our nearest extinct relatives - the Neanderthals and the Denisovans - there remain many unknowns regarding how differences in our genomes actually lead to differences in physical traits.

"When we're looking at archaic genomes, we don't have all the layers and marks that we usually have in samples from present-day individuals that help us interpret regulation in the genome, like RNA or cell structure," said David Gokhman, a postdoctoral fellow in biology at Stanford University.

"We ...