(Press-News.org) One of the great mysteries of modern space science is neatly summed up by the view from NASA's Perseverance, which just landed on Mars: Today it's a desert planet, and yet the rover is sitting right next to an ancient river delta.

The apparent contradiction has puzzled scientists for decades, especially because at the same time that Mars had flowing rivers, it was getting less than a third as much sunshine as we enjoy today on Earth.

But a new study led by University of Chicago planetary scientist Edwin Kite, an assistant professor of geophysical sciences and an expert on climates of other worlds, uses a computer model to put forth a promising explanation: Mars could have had a thin layer of icy, high-altitude clouds that caused a greenhouse effect.

"There's been an embarrassing disconnect between our evidence, and our ability to explain it in terms of physics and chemistry," said Kite. "This hypothesis goes a long way toward closing that gap."

Of the multiple explanations scientists had previously put forward, none have ever quite worked. For example, some suggested that a collision from a huge asteroid could have released enough kinetic energy to warm the planet. But other calculations showed this effect would only last for a year or two--and the tracks of ancient rivers and lakes show that the warming likely persisted for at least hundreds of years.

Kite and his colleagues wanted to revisit an alternate explanation: High-altitude clouds, like cirrus on Earth. Even a small amount of clouds in the atmosphere can significantly raise a planet's temperature, a greenhouse effect similar to carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

The idea had first been proposed in 2013, but it had largely been set aside because, Kite said, "It was argued that it would only work if the clouds had implausible properties." For example, the models suggested that water would have to linger for a long time in the atmosphere--much longer than it typically does on Earth--so the whole prospect seemed unlikely.

Using a 3D model of the entire planet's atmosphere, Kite and his team went to work. The missing piece, they found, was the amount of ice on the ground. If there was ice covering large portions of Mars, that would create surface humidity that favors low-altitude clouds, which aren't thought to warm planets very much (or can even cool them, because clouds reflect sunlight away from the planet.)

But if there are only patches of ice, such as at the poles and at the tops of mountains, the air on the ground becomes much drier. Those conditions favor a high layer of clouds--clouds that tend to warm planets more easily.

The model results showed that scientists may have to discard some crucial assumptions based on our own particular planet.

"In the model, these clouds behave in a very un-Earth-like way," said Kite. "Building models on Earth-based intuition just won't work, because this is not at all similar to Earth's water cycle, which moves water quickly between the atmosphere and the surface."

Here on Earth, where water covers almost three-quarters of the surface, water moves quickly and unevenly between ocean and atmosphere and land--moving in swirls and eddies that mean some places are mostly dry (the Sahara) and others are drenched (the Amazon). In contrast, even at the peak of its habitability, Mars had much less water on its surface. When water vapor winds up in the atmosphere, in Kite's model, it lingers.

"Our model suggests that once water moved into the early Martian atmosphere, it would stay there for quite a long time--closer to a year--and that creates the conditions for long-lived high-altitude clouds," said Kite.

NASA's newly landed Perseverance rover should be able to test this idea in multiple ways, too, such as by analyzing pebbles to reconstruct past atmospheric pressure on Mars.

Understanding the full story of how Mars gained and lost its warmth and atmosphere can help inform the search for other habitable worlds, the scientists said.

"Mars is important because it's the only planet we know of that had the ability to support life--and then lost it," Kite said. "Earth's long-term climate stability is remarkable. We want to understand all the ways in which a planet's long-term climate stability can break down--and all of the ways (not just Earth's way) that it can be maintained. This quest defines the new field of comparative planetary habitability."

INFORMATION:

The co-authors on the paper were former UChicago postdoctoral researcher Liam Steele, now with the Jet Propulsion Laboratory; Michael Mischna of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, and Mark Richardson of Aeolis Research. Parts of the analysis were performed at the University of Chicago Research Computing Center.

Citation: "Warm Early Mars surface enabled by high-altitude water ice clouds." Kite, Steele, Mischna, and Richardson, PNAS, April 26, 2021.

Funding: NASA.

Understanding spoken words, developing normal speech - cochlear implants enable people with profound hearing impairment to gain a great deal in terms of quality of life. However, background noises are problematic, they significantly compromise the comprehension of speech of people with cochlear implants. The team led by Tobias Moser from the Institute for Auditory Neuroscience and InnerEarLab at the University Medical Center Göttingen and from the Auditory Neuroscience and Optogenetics Laboratory at the German Primate Center - Leibniz Institute for Primate Research (DPZ) is therefore working to improve cochlear implants. The scientists want to use genetic engineering methods to make the nerve cells in the ear ...

MADISON, Wis. -- In October of 2020, Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier were awarded the Nobel Prize in chemistry for their discovery of an adaptable, easy way to edit genomes, known as CRISPR, which has transformed the world of genetic engineering.

CRISPR has been used to fight lung cancer and correct the mutation responsible for sickle cell anemia in stem cells. But the technology was also used by a Chinese scientist to secretly and illegally edit the genomes of twin girls -- the first-ever heritable mutation of the human germline made with genetic engineering.

"We've moved away from an era of science where we understood the risks that came with new technology and where decision stakes were ...

New findings detailing the world's first-of-its-kind estimate of how many people live in high-altitude regions, will provide insight into future research of human physiology.

Dr. Joshua Tremblay, a postdoctoral fellow in UBC Okanagan's School of Health and Exercise Sciences, has released updated population estimates of how many people in the world live at a high altitude.

Historically the estimated number of people living at these elevations has varied widely. That's partially, he explains, because the definition of "high altitude" does not have a fixed cut-off.

Using novel techniques, Dr. Tremblay's publication in the Proceedings of the National ...

New research reveals a genetic quirk in a small species of songbird in addition to its ability to carry a tune. It turns out the zebra finch is a surprisingly healthy bird.

A study published today in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences reveals that zebra finches and other songbirds have a low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) gene surprisingly different than other vertebrates.

The function of LDLR, which is responsible for cellular uptake of LDL-bound cholesterol, or "bad cholesterol," has been thought to be conserved across vertebrates. OHSU scientists found that in the case ...

Stomata, formed by a pair of kidney-shaped guard cells, are tiny pores in leaves. They act like mouths that plants use to "eat" and "breathe." When they open, carbon dioxide (CO2) enters the plant for photosynthesis and oxygen (O2) is released into the atmosphere. At the same time as gases pass in and out, a great deal of water also evaporates through the same pores by way of transpiration.

These "mouths" close in response to environmental stimuli such as high CO2 levels, ozone, drought and microbe invasion. The protein responsible for closing these "mouths" is an anion channel, called SLAC1, which moves negatively charged ions across the guard cell membrane to reduce turgor pressure. Low pressure causes the guard cells to collapse and subsequently the stomatal pore to ...

(Boston)--Lung carcinomas are the leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the United States and worldwide. Lung squamous cell carcinomas (non-small cell lung cancers that arise in the bronchi of the lungs and make up approximately 30 percent of all lung cancers) are poorly understood, particularly with respect to the cell type and signals that contribute to disease onset.

According to the researchers, treatments for lung squamous cell carcinomas are limited and research into the etiology of the disease is required to create new ways to treat it.

"Our study offers insight into how damage ...

A multi-institutional team of researchers has identified both the genetic abnormalities that drive pre-cancer cells into becoming an invasive type of head and neck cancer and patients who are least likely to respond to immunotherapy.

"Through a series of surprises, we followed clues that focused more and more tightly on specific genetic imbalances and their role in the effects of specific immune components in tumor development," said co-principal investigator Webster Cavenee, PhD, Distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of California San Diego School of Medicine.

"The genetic ...

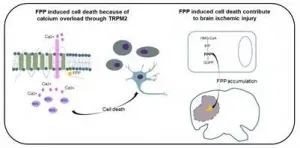

A vital intermediate in normal cell metabolism is also, in the right context, a trigger for cell death, according to a new study from Wanli Liu and Yonghui Zhang of Tsinghua University, and Yong Zhang of Peking University in Beijing, publishing 26th April 2021 in the open access journal PLOS biology. The discovery may contribute to a better understanding of the damage caused by stroke, and may offer a new drug target to reduce that damage.

Farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) is an intermediate in the mevalonate pathway, a series of biochemical reactions in every cell that contributes to protein synthesis, energy production, and construction of cell membranes. During a search for regulators of immune cell function, the authors unexpectedly discovered that FPP, when present at high concentrations ...

Patients hospitalized with COVID-19 may be at risk of developing heart failure even if they do not have a previous history of heart disease or cardiovascular risk factors, a new Mount Sinai study shows.

Researchers say that while these instances are rare, doctors should be aware of this potential complication. The study, published in the April 26 online issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, may prompt more monitoring of heart failure symptoms among patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

"This is one of the largest studies to date to specifically capture instances of new heart failure diagnosis among patients hospitalized ...

Skid marks left by cars are often analyzed for their impression patterns, but they often don't provide enough information to identify a specific vehicle. UCF Chemistry Associate Professor Matthieu Baudelet and his forensics team at the National Center for Forensic Science, which was established at UCF in 1997, may have just unlocked a new way to collect evidence from those skid marks.

The team recently published a study in the journal Applied Spectroscopy that details how they are classifying the chemical profile of tires to link vehicles back to potential crime ...