The tsunami's waves reached around six meters high, which was a shock to geophysicists who had believed that earthquakes along a strike-slip fault could only trigger far smaller tsunamis for that particular region. Now, new research describes a mechanism for these large tsunamis to form, and suggests that other coastal cities that were thought to be safe from massive tsunamis may need to reevaluate their level of risk.

Most large tsunamis are triggered by earthquakes along thrust faults, where one piece of crust is shoving its way over the top of another. Motion along such a fault creates a large vertical displacement, which, when the fault is under water, generates massive waves.

Strike-slip faults, by contrast, occur where two pieces of crust are moving horizontally and alongside one another, yielding very little vertical displacement.

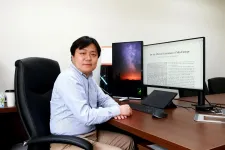

"Whenever we saw large tsunamis triggered by earthquakes along strike-slip faults, people assumed that perhaps the earthquake had caused an undersea landslide, displacing water that way," says Ares Rosakis, the Theodore von Kármán Professor of Aeronautics and Mechanical Engineering at Caltech and corresponding author of a paper on the new research that was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) on May 3.

About a month after the Palu tsunami, Rosakis attended a National Science Foundation (NSF) seismology workshop at Caltech organized by Nadia Lapusta, the Lawrence A. Hanson, Jr., Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Geophysics; there, he connected with Ahmed Elbanna (PhD '11), who worked with Lapusta and Professor of Engineering Seismology, Emeritus, Tom Heaton (PhD '78) while earning his degree at Caltech.

"The workshop wasn't supposed to be about Palu, but you get a bunch of seismologists together right after an event like that, and of course we'll be discussing it," says Elbanna, associate professor and Donald Biggar Willett faculty fellow at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UIUC), and lead author of the PNAS paper. "It puzzled the community. Why would these types of faults create this effect?"

At that time, very little was known about the quake. Early evidence suggested that the earthquake rupture had been supershear, meaning that the speed of the rupture exceeded the velocity of seismic shear waves. The existence of supershear ruptures was first discovered experimentally at Caltech in 2000 by Rosakis and Hiroo Kanamori, the John E. and Hazel S. Smits Professor of Geophysics, Emeritus.

These hyper-fast earthquakes tend to occur on long faults (on the order of 100 kilometers or more), where the rupture can gain speed as it rips along. The phenomenon is much like an aircraft breaking the speed of sound, generating a Mach wave that manifests as a sonic boom; in the case of hyper-fast earthquakes, a destructive Mach wave front is emitted from the fast-traveling tip of the rupture zone.

"Ares is a pioneer in the area of supershear quakes, and Palu was a supershear quake, so we started questioning whether there was a connection that created the tsunami," Elbanna says.

"I always suspected that the supershear nature of the quake was the reason, and I thought that the interaction of the Mach fronts with sides of the Palu bay may have had something to do with it. I shared my thoughts with Ahmed, and we decided to join forces and numerically explore this issue," Rosakis says. "A few months later, we also joined forces with my longtime collaborators in France: Harsha Bhat of ENS, my former postdoc at Caltech; and Faisal Amlani (PhD '13). They were also looking at a possible connection between the supershear nature of the earthquake and the tsunami characteristics at Palu and had, by that time, obtained conclusive evidence, from near-fault GPS station data, that the Palu rupture was indeed supershear," Rosakis adds.

To jump-start this research, Rosakis and Elbanna pooled funding. Elbanna used funding from his NSF CAREER award that supports his research on faults and fluids. Rosakis applied for and quickly received seed funding from the Caltech/Mechanical and Civil Engineering (MCE) Big Ideas Fund, established in 2018 by members of MCE's External Advisory Board including chairman and alumnus Lon Bell (BS '62; MS '63, PhD '68), founder of Gentherm.

Meanwhile, in then-unrelated work, Costas Synolakis (BS '78, MS '79, PhD '86), an expert on tsunamis and tsunami-hazard mitigation, was also trying to learn more about what happened at Palu. Synolakis, who is currently president of Athens College in Greece while on sabbatical from his position as professor of civil/environmental engineering at the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, convinced the Indonesian government to let him bring a small team of scientists to the area shortly after the disaster to document any ephemeral evidence that might explain the cause of the large tsunami.

Funded by an NSF grant, Synolakis and his crew of five researchers arrived in Palu about three weeks after the tsunami and deployed airborne drones, shot video, interviewed eyewitnesses, and conducted surveys using LIDAR (an acronym for Light Detection and Ranging; a three-dimensional laser-scanning technology). "The tsunami was totally out of scale, about three times the size you'd expect." Synolakis says. "We carefully documented the impact of the tsunami and its height. And then we had to think, 'How could this have happened from an earthquake that was not supposed to do this?'"

Synolakis and his team stayed in the devastated area for a week, trying to learn as much as they could before the evidence was erased as the cleanup and reconstruction began. "The hardest part is talking to people about something like that," Synolakis says. "It looked like a bulldozer had come in and leveled the town. We talked to the relatives and friends of people who had died; people whose homes and possessions were all washed away. This is why it is so important that we try to understand what really happened."

When he returned to the States, Synolakis talked to his old friend Rosakis about what he had seen. Synolakis and Rosakis attended Athens College together in the early 1970s.

While their research does not typically overlap--Rosakis deals with the solid mechanics of the moving earth, while Synolakis deals more with the fluid mechanics of the ocean--in this case, they found common ground, so to speak. "Here, we are coupling solid mechanics with fluid mechanics," Rosakis says. "The fully 3-D solid mechanics model creates the earthquake, which shakes the seafloor and walls of the bay and drives a fluid-mechanics event with the water that is sitting inside."

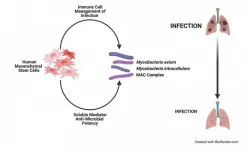

Through 3-D computer simulations conducted by the two UIUC graduate students, Mohamed Abdelmeguid and Xiao Ma, the team found that a supershear strike-slip earthquake that occurs beneath a narrow, shallow bay can trigger a massive tsunami. Even though the earthquake does not cause a major vertical displacement, the sides of the bay almost instantaneously interact with the substantial horizontal displacements carried by the Mach fronts of the supershear rupture. The sides of the bay then focus and direct the supershear rupture's energy, much like the walls of a bathtub direct bathwater sloshed around by a child. After that initial mega-jolt sends water sloshing vertically, gravity takes over and a tsunami is created.

"What is unique about our study is that we focused on extracting the fundamental mechanisms through which a strike-slip fault system interacting with the boundaries of a narrow bay may possess enough potential for triggering destructive tsunamis," Elbanna said. "We opted to simulate a very basic, planar fault passing through a very simplified smooth-bottomed bay similar to a bathtub. Having this simplified baseline model allows us to generalize to any place on the planet that may be at risk."

The computer simulations generated by the team matched the field evidence that Synolakis had gathered. For example, the simulation suggested that a strike-slip fault, in which one side slides one direction and the other side slides the opposite way, would generate an asymmetric tsunami wave with greater inundation on one side of the fault than the other. Images of the damage at Palu show exactly that.

Furthermore, the model identified three distinct phases of the tsunami's motion: an instantaneous dynamic phase right as the rupture crosses the bay; a co-seismic lagging phase that occurs as the rupture has passed by, but the earthquake waves are still shaking an affected region; and a post-seismic phase dominated by gravity as well as reflections and wave-focusing from the shore and bay apex. Each may affect coastal areas differently.

"The tsunami risk from strike-slip faulting needs to be reevaluated," Rosakis says. He notes that similar conditions exist along the San Andreas Fault in the Bay Area, as well as in the highly developed Gulf of Aqaba that shares coastline with Egypt, Israel, Jordan, and Saudi Arabia.

INFORMATION:

The PNAS paper is titled "Anatomy of Strike-Slip Fault Tsunami-genesis." Co-authors include UIUC's Abdelmeguid and Ma; Faisal Amlani (PhD '14) of USC; and Harsha S. Bhat of the École Normale Supérieure in France. This research was funded by the NSF, the MCE Big Ideas Fund, and the Caltech Terrestrial Hazard Observation and Reporting Center (THOR). This research is part of the Blue Waters sustained-petascale computing project, which is supported by the NSF, the State of Illinois, and the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency. Blue Waters is a joint effort of UIUC and its National Center for Supercomputing Applications.