(Press-News.org) A new Boston University School of Public Health (BUSPH) study has identified for the first time how the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), an environmental chemical receptor, drives immunosuppression in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC)--and that its removal from malignant cells can result in tumor rejection.

Published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study findings provide new insight into the biology of cancer immunosuppression, and identify a new target for cancer immunotherapy treatment.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (immunotherapy drugs) are some of the most important treatments that have emerged for treating many cancers, including OSCC. Targeting immune checkpoint molecules such as PD-1, PD-L1 and CTLA4 has demonstrated that immunosuppression plays a significant role in OSCC pathology. But immune checkpoint inhibitors are only effective for about 30 percent of cancer patients, so there is a critical need for researchers to identify new immunotherapy targets.

"This study illustrates how studying the basic science of common environmental pollutants' suppression of the immune system can result in a hugely impactful new approach to cancer prevention and immunotherapy," says Dr. David Sherr, study lead author and a professor of environmental health at BUSPH. The study was conducted in his lab, the Sherr Lab, located in the Department of Environmental Health at SPH.

Dr. Zhongyan Wang, a postdoctoral fellow at SPH and a co-author of the study, used gene-editing techniques to delete a single gene that encodes the AhR, an environmental chemical receptor, from highly malignant mouse oral cancer cells.

After these minimally altered cancer cells were transplanted into normal mice, Jessica Kenison-White, first author of the study, measured tumor growth and compared the strength and nature of the immune response to the cancer cells with the ineffective immune response to the unaltered cancer cells, using digital gene-expression technologies and laser-based enumeration of immune cells. Kenison-White was a PhD student at Boston University School of Medicine (MED) and a research scientist at the Sherr Lab during the study.

The researchers found that while unaltered tumor cells overwhelmed the mice within 60 days, AhR gene deletion resulted in zero tumor growth.

This lack of growth, they found, was accompanied by a remarkably robust tumor-specific immune response characterized by a profound decrease in expression of immune checkpoint markers, which mediate immune suppression.

The researchers also discovered that the mice transplanted with AhR-negative oral cancer cells in a kind of vaccine protocol were now 100 percent immune to a challenge with unaltered, highly malignant cancer cells.

"We believe that these findings identified a potential master regulator of multiple immune checkpoints--the suppressive components of the immune system that have been individually targeted in recent years with immunotherapeutics in a way that has revolutionized cancer treatment," says Sherr.

"These results strongly suggest that targeting this master immune checkpoint regulator with specific inhibitors may ultimately prove as effective, or more effective, at enhancing anti-cancer immune responses than any single immune checkpoint inhibitor," Sherr says. "We can see how such a novel drug could be used in a cancer prevention, interception, or treatment modality."

INFORMATION:

The study was also coauthored by Kangkang Yang, a research assistant in the Department of Environmental Health at SPH; Megan Snyder, a PhD student at MED and research scientist in the Sherr Lab; and Francisco J. Quintana, associate scientist at Brigham and Women's Hospital and professor of neurology at Harvard Medical School.

About the Boston University School of Public Health

Founded in 1976, the Boston University School of Public Health is one of the top five ranked private schools of public health in the world. It offers master's- and doctoral-level education in public health. The faculty in six departments conduct policy-changing public health research around the world, with the mission of improving the health of populations--especially the disadvantaged, underserved, and vulnerable--locally and globally.

Measures to contain the Corona pandemic are the subject of politically charged debate and tend to polarize segments of the population. Those who support the measures motivate their acquaintances to follow the rules, while those who oppose them call for resistance in social media. But how exactly do politicization and social mobilization affect the incidence of infection? Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development have examined this question using the USA as an example. Their findings were published in Applied Network Science.

Limit crowds, keep a safe distance, and wear masks. Such non-pharmaceutical ...

Cancerous tumors thrive on blood, extending their roots deep into the fabric of the tissue of their host. They alter the genetics of surrounding cells and evolve to avoid the protective attacks of immune cells. Now, Penn State researchers have developed a way to study the relationship between solid, difficult-to-treat tumors and the microenvironment they create to support their growth.

The method has the potential to act as a testbed for drugs and other anticancer treatments, according to Ibrahim T. Ozbolat, associate professor of engineering science and mechanics and biomedical engineering, who led the research. The details of the approach were published in Advanced Biology.

Using ...

Despite human inventiveness and ingenuity, we still lag far behind the elegant and efficient solutions forged by nature over millions of years of evolution.

This also applies for buildings, where animals and plants, have developed extremely effective digging methods, for example, that are far more energy-efficient than modern tunnelling machines, and even self-repairing foundations that are unusually resistant to erosion and earthquakes (yep, we're talking about roots here).

Researchers from all over the world are therefore seeking inspiration in nature to develop the buildings of the future, and researchers from Aarhus University ...

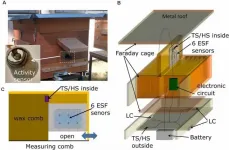

Honeybees have a complex communication system. Between buzzes and body movements, they can direct hive mates to food sources, signal danger, and prepare for swarming - all indicators of colony health. And now, researchers are listening in.

Scientists based in Germany - with collaborators in China and Norway - have developed a way to monitor the electrostatic signals that bees give off. Basically, their wax-covered bodies charge up with electrostatic energy due to friction when flying, similar to how rubbing your hair can make it stand on end. That energy then gets emitted during communications.

"We were thrilled by the ...

The majority of top-rated fertility apps collect and even share intimate data without the users' knowledge or permission, a collaborative study by Newcastle University and Umea University has found.

Researchers are now calling for a tightening of the categorisation of these apps by platforms to protect women from intimate and deeply personal information being exploited and sold.

For hundreds of millions of women fertility tracking applications offer an affordable solution when trying to conceive or manage their pregnancy. But as this technology grows in popularity, experts have revealed that most of the top-rated fertility apps collect and share sensitive ...

T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (T-ALL) is a very aggressive type of blood cancer. It is relatively rare but still draws a lot of attention as it mostly develops in children under the age of 20. The standard treatment for T-ALL involves heavy chemotherapy procedures, which result in favorable outcomes with an overall survival of 75% after 5 years.

However, some patients do not respond to this treatment, or they only respond for a short period, after which the disease grows back. These patients therefore need alternative therapies.

Researchers from the Faculty of Health and Medical Sciences, University of Copenhagen, have now identified a combination treatment, which could potentially benefit patients ...

University of Bristol research into octopus vision has led to a quick and easy test that helps optometrists identify people who are at greater risk of macular degeneration, the leading cause of incurable sight loss.

The basis for this breakthrough was published in the latest issue of the Journal of Experimental Biology and describes new technology developed by lead researcher, Professor Shelby Temple, to measure how well octopus- which are colour-blind - could detect polarized light, an aspect of light that humans can't readily see. Using this novel technology, the research team showed that octopus have the most sensitive polarization vision system of any animal tested to date. Subsequent research ...

When COVID-19 patients began filling up ICUs throughout the country in 2020, health care providers faced difficult decisions. Health care workers had to decide which patients were most likely to recover with care and which were not so resources could be prioritized.

But a new paper from the University of Georgia suggests that unconscious biases in the health care system may have influenced how individuals with intellectual disabilities were categorized in emergency triage protocols.

The state-level protocols, while crucial for prioritizing care during disasters, frequently ...

(Boston)--If you come from a family where people routinely live well into old age, you will likely have better cognitive function (the ability to clearly think, learn and remember) than peers from families where people die younger. Researchers affiliated with the Long Life Family Study (LLFS) recently broadened that finding in a paper published in END ...

Brain implants are used to treat neurological dysfunction, and their use for enhancing cognitive abilities is a promising field of research. Implants can be used to monitor brain activity or stimulate parts of the brain using electrical pulses. In epilepsy, for example, brain implants can determine where in the brain seizures are happening.

Over time, implants trigger a foreign body response, creating inflammation and scar tissue around the implant that reduces their effectiveness.

The problem is that traditional implants are much more rigid than brain tissue, which has a softness comparable to pudding. Stress between the implant and ...