(Press-News.org) Coronavirus (CoVs) infection in animals and humans is not new. The earliest papers in the scientific literature of coronavirus infection date to 1966. However, prior to SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and SARS-CoV-2, very little attention had been paid to coronaviruses.

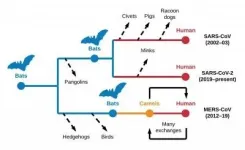

Suddenly, coronaviruses changed everything we know about personal and public health, and societal and economic well-being. The change led to rushed analyses to understand the origins of coronaviruses in humans. This rush has led to a thus far fruitless search for intermediate hosts (e.g., civet in SARS-CoV and pangolin in SARS-CoV-2) rather than focusing on the important work, which has always been surveillance of SARS-like viruses in bats.

To clarify the origins of coronavirus' infections in humans, researchers from the Bioinformatics Research Center (BRC) at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte (UNC Charlotte) performed the largest and most comprehensive evolutionary analyses to date. The UNC Charlotte team analyzed over 2,000 genomes of diverse coronaviruses that infect humans or other animals.

"We wanted to conduct evolutionary analyses based on the most rigorous standards of the field," said Denis Jacob Machado, the first author of the paper. "We've seen rushed analyses that had different problems. For example, many analyses had poor sampling of viral diversity or placed excessive emphasis on overall similarity rather than on the characteristics shared due to common evolutionary history. It was very important to us to avoid those mistakes to produce a sound evolutionary hypothesis that could offer reliable information for future research."

The study's major conclusions are:

1) Bats have been ancestral hosts of human coronaviruses in the case of SARS-CoV and SARS-CoV-2. Bats also were the ancestral hosts of MERS-CoV infections in dromedary camels that spread rapidly to humans.

2) Transmission of MERS-CoV among camels and their herders evolved after the transmission from bats to these hosts. Similarly, there was transmission of SARS-CoV after the bat to human transmission among human vendors and their civets. These events are similar to the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 by fur farmers to their minks. The evolutionary analysis in this study helps to elucidate that these events occurred after the original human infection from lineages of coronaviruses hosted in bats. Therefore, these secondary transmissions to civet or mink did not play a role in the fundamental emergence of human coronaviruses.

3) The study corroborates the animal host origins of other human coronaviruses, such as HCoV-NL63 (from bat hosts), HCoV-229E (from camel hosts), HCoV-HKU1 (from rodent hosts) and HCoV-OC43 and HECV-4408 (from cow hosts).

4) Transmission of coronaviruses from animals to humans occurs episodically. From 1966 to 2020, the scientific community has described eight human-hosted lineages of coronaviruses. Although it is difficult to predict when a new human hosted coronavirus could emerge, the data indicate that we should prepare for that possibility.

"As coronavirus transmission from animal to human host occurs episodically at unpredictable intervals, it is not wise to attempt to time when we will experience the next human coronavirus," noted professor Daniel A. Janies, Carol Grotnes Belk Distinguished Professor of Bioinformatics and Genomics and team leader for the study. "We must conduct research on viruses that can be transferred from animals to humans on a continuous rather than reactionary basis."

UNC Charlotte researchers analyzed the host origins of SARS-CoV-2 and other coronaviruses

2021-05-04

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

With a zap of light, system switches objects' colors and patterns

2021-05-04

When was the last time you repainted your car? Redesigned your coffee mug collection? Gave your shoes a colorful facelift?

You likely answered: never, never, and never. You might consider these arduous tasks not worth the effort. But a new color-shifting "programmable matter" system could change that with a zap of light.

MIT researchers have developed a way to rapidly update imagery on object surfaces. The system, dubbed "ChromoUpdate" pairs an ultraviolet (UV) light projector with items coated in light-activated dye. The projected light alters the reflective properties of the dye, creating colorful new images in just a few minutes. The advance could accelerate product development, enabling product designers to churn through ...

Citrus derivative makes transparent wood 100 percent renewable

2021-05-04

Since it was first introduced in 2016, transparent wood has been developed by researchers at KTH Royal Institute of Technology as an innovative structural material for building construction. It lets natural light through and can even store thermal energy.

The key to making wood into a transparent composite material is to strip out its lignin, the major light-absorbing component in wood. But the empty pores left behind by the absence of lignin need to be filled with something that restores the wood's strength and allows light to permeate.

In earlier versions of the composite, researchers at KTH's Wallenberg Wood Science Centre used fossil-based polymers. Now, the researchers have successfully tested an eco-friendly alternative: limonene acrylate, a monomer made ...

Phase transition inside the nucleus provides oncogenic function to mutant p53 in cancer

2021-05-04

Cancer has been recently shown to be affected by protein clusters, particularly by the aggregation of mutant variants of the tumor suppressor protein p53, which are present in more than half of malignant tumors. However, how the aggregates are formed is not yet fully understood. The understanding of this process is expected to provide new therapeutic tools able to prevent proteins to clump and cancer progression.

In Brazil, researchers at the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro have identified a key mechanism behind the mutant p53 aggregation process, linked to cancer pathology, opening new paths for the development of novels ...

MDI Biological Laboratory scientist identifies process critical to kidney function

2021-05-04

BAR HARBOR, MAINE — Our kidneys are charged with the extraordinary task of filtering about 53 gallons of fluid a day, a process that depends on podocytes, tiny, highly specialized cells in the cluster of blood vessels in the kidney where waste is filtered that are highly vulnerable to damage.

In research at the MDI Biological Laboratory in Bar Harbor, Maine, a team led by Iain Drummond, Ph.D., director of the Kathryn W. Davis Center for Regenerative Biology and Aging, has identified the signaling mechanisms underlying podocyte formation, or morphogenesis. The discovery opens the door to ...

U of A researchers successfully use 3-D 'bioprinting' to create nose cartilage

2021-05-04

A team of University of Alberta researchers has discovered a way to use 3-D bioprinting technology to create custom-shaped cartilage for use in surgical procedures. The work aims to make it easier for surgeons to safely restore the features of skin cancer patients living with nasal cartilage defects after surgery.

The researchers used a specially designed hydrogel--a material similar to Jell-O--that could be mixed with cells harvested from a patient and then printed in a specific shape captured through 3-D imaging. Over a matter of weeks, the material is cultured in a lab to become functional cartilage.

"It takes a lifetime to make cartilage in an individual, while this method takes about four weeks. So you still expect ...

Emissive supramolecular metallacages via coordination-driven self-assembly

2021-05-04

Metallacages prepared via coordination-driven self-assembly have received extensive attention because of their three-dimensional layout and cavity-cored nature. The construction of light-emitting materials employing metallacages as a platform has also gained significant interest due to their good modularity in photophysical properties, which bring emerging applications in fields as diverse as sensing, biomedicine, and catalysis.

However, the luminescence efficiency of conventional luminophores significantly decreases in the aggregate state because they encounter unfavorable aggregation-caused quenching (ACQ). Therefore, it was quite a challenge to fabricate light-emitting metallacages with high luminescence efficiency in various physical states.

In 2001, Tang's group ...

Our immune systems blanket the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein with antibodies

2021-05-04

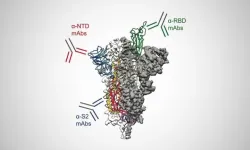

The most complete picture yet is coming into focus of how antibodies produced in people who effectively fight off SARS-CoV-2 work to neutralize the part of the virus responsible for causing infection. In the journal Science, researchers at The University of Texas at Austin describe the finding, which represents good news for designing the next generation of vaccines to protect against variants of the virus or future emerging coronaviruses.

Previous research focused on one group of antibodies that target the most obvious part of the coronavirus's spike protein, called the receptor-binding domain (RBD). Because the RBD is the part of the spike that attaches directly to human cells and enables the virus to infect them, ...

Breakthrough study shows no-take marine reserves benefit overfished reefs

2021-05-04

New York, NY (May 4, 2021) - A powerful, long-term study from WCS adds scientific backing for global calls for conserving 30 percent of the world's ocean. The studied no-take marine protected areas (MPAs) increased the growth of fish populations by 42 percent when fishing was unsustainable in surrounding areas, achieving the benefits of stable and high production of fish populations for fishers, while protecting threatened ecosystems.

The study recorded fish catches for 24-years across a dozen fish landing sites within two counties in Kenya, which allowed scientists to evaluate the long-term impacts of two different fisheries management methods. While one county ...

Juvenile incarceration has mixed effects on future convictions

2021-05-04

Harsh prison sentences for juvenile crimes do not reduce the probability of conviction for violent crimes as an adult, and actually increase the propensity for conviction of drug-related crimes, finds a new study by economists at UC Riverside and the University of Louisiana. Harsh juvenile sentences do reduce the likelihood of conviction for property crimes as an adult. But the increase in drug-related crimes cancels out any benefit harsh sentences might offer, researchers found.

"Juvenile incarceration is a double-edged sword which deters future property crimes but makes drug convictions more likely in adulthood. Thus, it's hard to make firm policy recommendations ...

Your stomach may be the secret to fighting obesity

2021-05-04

Scientists believe a stomach-specific protein plays a major role in the progression of obesity, according to new research in Scientific Reports. The study co-authored by an Indiana University School of Medicine researcher, could help with development of therapeutics that would help individuals struggling with achieving and maintaining weight loss.

Researchers focused on Gastrokine-1 (GKN1) -- a protein produced exclusively and abundantly in the stomach. Previous research has suggested GKN1 is resistant to digestion, allowing it to pass into the intestine and interact with microbes in the gut.

In the Scientific Reports study, researchers show that inhibiting GKN1 produced significant differences in weight and levels of body fat in comparison to when the protein was expressed.

"While ...