(Press-News.org) PITTSBURGH, May 5, 2021 - Subtle differences in the shape of the brain that are present in adolescence are associated with the development of psychosis, according to an international team led by neuroscientists at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine and Maastricht University in the Netherlands.

In results published today in JAMA Psychiatry, the differences are too subtle to detect in an individual or use for diagnostic purposes. But the findings could contribute to ongoing efforts to develop a cumulative risk score for psychosis that would allow for earlier detection and treatment, as well as targeted therapies. The discovery was made with the largest-ever pooling of brain scans in children and young adults determined by psychiatric assessment to be at high risk of developing psychosis.

"These results were, in a sense, sobering," said Maria Jalbrzikowski, Ph.D., assistant professor of psychiatry at Pitt. "On the one hand, our data set includes 600% more high-risk youth who developed psychosis than any existing study, allowing us to see statistically significant results in brain structure. But the variance between whether or not a high-risk youth develops psychosis is so small that it would be impossible to see a difference at the individual level. More work is needed for our findings to be translated into clinical care."

Psychosis is an umbrella term for a constellation of severe mental disorders that cause people to have difficulty determining what is real and what is not. Most often, individuals have hallucinations where they see or hear things that others do not. They also may have strongly held beliefs, or delusions, even when most people do not believe them. Schizophrenia is only one disorder associated with psychosis, and psychotic symptoms can occur in other psychiatric disorders, such as bipolar disorder, depression, body dysmorphic disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder. In people who receive a diagnosis of psychosis, there is a great deal of heterogeneity in outcomes over time.

Diagnosis usually happens in later adolescence and early adulthood, but most often symptoms begin to manifest in the teen years, when clinicians can use psychological assessments to determine a person's risk of developing full-blown psychosis.

Jalbrzikowsi and Dennis Hernaus, Ph.D., assistant professor in the School of Mental Health and Neuroscience at Maastricht University, are co-chairs of the Enhancing Neuro Imaging Genetics Through Meta-Analysis (ENIGMA) Clinical High Risk for Psychosis Working Group. This group pooled structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans from 3,169 volunteer participants at an average age of 21 who were recruited at 31 different institutions. About half--1,792 of the participants--had been determined to be at "clinical high risk for developing psychosis." Of those high-risk participants, 253 went on to develop psychosis within two years. The co-chairs emphasized that this study would not be possible without the collaborative efforts of the 100-plus researchers involved.

When looking at all the scans together, the team found that those at high risk for psychosis had widespread lower cortical thickness, a measure of the thickness of the brain's gray matter. In high-risk youth who later developed psychosis, a thinner cortex was most pronounced in several temporal and frontal regions.

Everyone goes through a cortical thinning process as they develop into an adult, but the team found that in younger participants between 12 and 16 years old who developed psychosis the thinning was already present. These high-risk youth who developed psychosis also progressed at a slower rate than in the control group.

"We don't yet know exactly what this means, but adolescence is a critical time in a child's life--it's a time of opportunity to take risks and explore, but also a period of vulnerability," Jalbrzikowski said. "We could be seeing the result of something that happened even earlier in brain development but only begins to influence behavior during this developmental stage."

Hernaus stressed that these findings underscore the importance of early detection and intervention in people who show risk factors for developing psychosis, which include hearing whispers from voices that aren't there and a family history of psychosis.

"Until now, researchers have primarily studied how the brains of people with clinical high risk for psychosis differ at a given point in time," Hernaus said. "An important next step is to better understand brain changes over time, which could provide new clues on underlying mechanisms relevant to psychosis."

INFORMATION:

Other authors for this study are the members of the ENIGMA Clinical High Risk for Psychosis Working Group, listed in the JAMA Psychiatry manuscript.

This research received support from numerous funders listed in the JAMA Psychiatry manuscript. Jalbrzikowski received support from National Institute of Mental Health grant K01 MH112774.

To read this release online or share it, visit http://www.upmc.com/media/news/050521-Jalbrzikowski-ENIGMA.

About the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine

As one of the nation's leading academic centers for biomedical research, the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine integrates advanced technology with basic science across a broad range of disciplines in a continuous quest to harness the power of new knowledge and improve the human condition. Driven mainly by the School of Medicine and its affiliates, Pitt has ranked among the top 10 recipients of funding from the National Institutes of Health since 1998. In rankings recently released by the National Science Foundation, Pitt ranked fifth among all American universities in total federal science and engineering research and development support.

Likewise, the School of Medicine is equally committed to advancing the quality and strength of its medical and graduate education programs, for which it is recognized as an innovative leader, and to training highly skilled, compassionate clinicians and creative scientists well-equipped to engage in world-class research. The School of Medicine is the academic partner of UPMC, which has collaborated with the University to raise the standard of medical excellence in Pittsburgh and to position health care as a driving force behind the region's economy. For more information about the School of Medicine, see http://www.medschool.pitt.edu.

http://www.upmc.com/media

Contact: Allison Hydzik

Office: 412-647-9975

Mobile: 412-559-2431

E-mail: HydzikAM@upmc.edu

Contact: Ashley Trentrock

Mobile: 412-529-9092

E-mail: TrentrockAR@upmc.edu

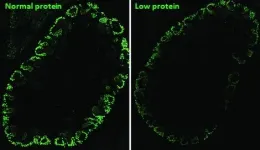

Besides being underweight, babies born to women whose diet lacked sufficient protein during pregnancy tend to have kidney problems resulting from alterations that occurred while their organs were forming during the embryonic stage of their development.

In a study published in PLOS ONE, researchers affiliated with the University of Campinas (UNICAMP) in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, discovered the cause of the problem at the molecular level and its link to epigenetic phenomena (changes in gene expression due to environmental factors such as stress, exposure to toxins or malnutrition, among others).

According to the authors, between 10% and 13% of the world population ...

Researchers from the University of Liverpool have shown the potential of repurposing an existing and cheap drug into a long-acting injectable therapy that could be used to treat Covid-19.

In a paper published in the journal Nanoscale, researchers from the University's Centre of Excellence for Long-acting Therapeutics (CELT) demonstrate the nanoparticle formulation of niclosamide, a highly insoluble drug compound, as a scalable long-acting injectable antiviral candidate.

The team started repurposing and reformulating identified drug compounds with the potential for COVID-19 therapy candidates within weeks of the first lockdown. Niclosamide is just one of the drug compounds identified and has been shown to be highly effective against SARS-CoV-2 in a number of laboratory studies.

Using ...

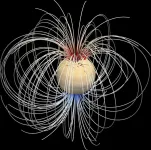

New Johns Hopkins University simulations offer an intriguing look into Saturn's interior, suggesting that a thick layer of helium rain influences the planet's magnetic field.

The models, published this week in AGU Advances, also indicate that Saturn's interior may feature higher temperatures at the equatorial region, with lower temperatures at the high latitudes at the top of the helium rain layer.

It is notoriously difficult to study the interior structures of large gaseous planets, and the findings advance the effort to map Saturn's hidden regions.

"By ...

The incorporation of boron into polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon systems leads to interesting chromophoric and fluorescing materials for optoelectronics, including organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDS) and field-effect transistors, as well as polymer-based sensors. In the journal Angewandte Chemie, a research team has now introduced a new anionic organoborane compound. Synthesis of the borafluorene succeeded through the use of carbenes.

Borafluorene is a particularly interesting boron-containing building block. It is a system of three carbon rings joined at the edges: two six-membered and one central five-membered ring, whose free tip is the boron atom. While neutral, radical, and cationic (positively ...

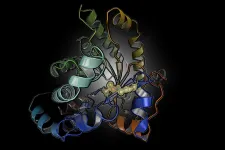

Proteins perform a vast array of functions in the cell of every living organism with critical roles in almost every biological process. Not only do they run our metabolism, manage cellular signaling and are in charge of energy production, as antibodies they are also the frontline workers of our immune system fighting human pathogens like the coronavirus. In view of these important duties, it is not surprising that the activity of proteins is tightly controlled. There are numerous chemical switches that control the structure and, therefore, the function of proteins in response to changing environmental conditions and stress. ...

Philadelphia, May 5, 2021--When Luke Terrio was about seven months old, his mother began to realize something was off. He had constant ear infections, developed red spots on his face, and was tired all the time. His development stagnated, and the antibiotics given to treat his frequent infections stopped working. His primary care doctor at Children's Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) ordered a series of blood tests and quickly realized something was wrong: Luke had no antibodies.

At first, the CHOP specialists treating Luke thought he might have X-linked agammaglobulinemia (XLA), a rare immunodeficiency syndrome seen in children. However, as the CHOP research team continued investigating Luke's case, they realized Luke's condition was unlike any disease described ...

Pesticides have been used in European agriculture for more than 70 years, so monitoring their presence, levels and their effects in European soils quality and services is needed to establish protocols for the use and the approval of new plant protection products.

In an attempt to deal with this issue, a team led by the prof. Dr. Violette Geissen from Wageningen University (Netherlands) have analysed 340 soil samples originating from three European countries to compare the contentdistribution of pesticide cocktails in soils under organic farming practices and soils under conventional practices. This study was a combined effort of 3 EC funded projects addressing soil

quality: RECARE (http://www.recare-project.eu/), iSQAPER (http://www.isqaper-project.eu) ...

T-cells play a central role in our immune system: by means of their so-called T-cell receptors (TCR) they make out dangerous invaders or cancer cells in the body and then trigger an immune reaction. On a molecular level, this recognition process is still not sufficiently understood.

Intriguing observations have now been made by an interdisciplinary Viennese team of immunologists, biochemists and biophysicists. In a joint project funded by the Vienna Science and Technology Fund and the FWF, they investigated which mechanical processes take place when an antigen is recognized: ...

Larger bumblebees are more likely to go out foraging in the low light of dawn, new research shows.

University of Exeter scientists used RFID - similar technology to contactless card payments - to monitor when bumblebees of different sizes left and returned to their nest.

The biggest bees, and some of the most experienced foragers (measured by number of trips out), were the most likely to leave in low light.

Bumblebee vision is poor in low light, so flying at dawn or dusk raises the risk of getting lost or being eaten by a predator.

However, the bees benefit from extra foraging time and fewer competitors for pollen in the early morning.

"Larger bumblebees have bigger eyes than their smaller-sized nest mates and many other bees, and can therefore see better in dim light," said lead author ...

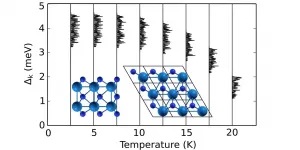

Superconductivity in two-dimensional (2D) systems has attracted much attention in recent years, both because of its relevance to our understanding of fundamental physics and because of potential technological applications in nanoscale devices such as quantum interferometers, superconducting transistors and superconducting qubits.

The critical temperature (Tc), or the temperature under which a material acts as a superconductor, is an essential concern. For most materials, it is between absolute zero and 10 Kelvin, that is, between -273 Celsius and -263 Celsius, too cold to be of any practical use. Focus has then been on finding materials with a higher Tc.

While researchers have discovered materials ...