(Press-News.org) New research on the growth rates of coral reefs shows there is still a window of opportunity to save the world's coral reefs--but time is running out.

The international study was initiated at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (Coral CoE), which is headquartered at James Cook University (JCU).

Co-author Professor Morgan Pratchett from Coral CoE at JCU said the results show that unless carbon dioxide emissions are drastically reduced the growth of coral reefs will be stunted.

"The threat posed by climate change to coral reefs is already very apparent based on recurrent episodes of mass coral bleaching," Prof Pratchett said. "But changing environmental conditions will have other far-reaching consequences."

Co-author Professor Ryan Lowe, from Coral CoE at The University of Western Australia (UWA), said modern coral reef structures reflect a balance between a wide range of organisms that build reefs, not just corals. This includes coralline algae--a rock-hard alga that bind reefs together.

"While the responses of individual reef organisms to climate change are increasingly clear, this study uniquely examines how the complex interactions between diverse communities of organisms responsible for maintaining present day coral reefs will likely change reef structures in the future," Prof Lowe said.

The joint lead authors, Dr Christopher Cornwall and Dr Steeve Comeau (who are now at Victoria University of Wellington and Sorbonne Université CNRS Laboratoire d'Océanographie de Villefranche sur Mer, respectively) calculated how coral reef growth is likely to react to ocean acidification and warming under three different climate-change carbon dioxide scenarios: low, medium and worst-case.

The findings suggest that under an intermediate emissions scenario, some reefs may even keep pace with sea-level rise by growing--but only for a short while.

"All reefs around the world will be eroding by the end of the century under the intermediate scenario," said co-author Dr Scott Smithers, from JCU. "This will obviously have serious implications for reefs, reef islands, as well as the people and other organisms depending upon coral reefs."

The study gives broader projections of ocean warming and acidification--and their interaction--on the net carbonate production of coral reefs.

Warming oceans bring more marine heatwaves, which cause mass coral bleaching. Ocean acidification affects the ability of calcifying corals to form their calcium carbonate skeletons, a process called 'calcification'. Warming waters also reduce calcification.

The data in the study include net calcification, bioerosion and sediment dissolution rates measured or collated from 233 locations across 183 distinct reefs. 49% of the reefs were in the Atlantic Ocean, 39% in the Indian Ocean and 11% in the Pacific Ocean.

These were then modelled against three Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change emissions scenarios for low, medium and high-impact outcomes on ocean warming and acidification for 2050 and 2100.

The projections show that even under the low-impact case, reefs will suffer severely reduced growth, or accretion, rates.

"While 63% of reefs are projected to continue to accrete by 2100 under the low-impact pathway, 94% will be eroding by 2050 under the worse-case scenario," Dr Cornwall said. "And no reef will continue to accrete at rates matching projected sea-level rise under the medium and high-impact scenarios by 2100."

"Our study shows changing environmental conditions challenge the growth of reef-building corals and other calcifying organisms, which are important in maintaining the structure of reef systems," Prof Pratchett said.

"Saving coral reefs requires immediate and drastic reductions in global carbon emissions."

INFORMATION:

PAPER

Cornwall C, Comeau S, Korndere N, Perry C, Van Hooidon R, DeCarlo T, Pratchett M, Anderson K, Browne N, Carpenter R, Diaz-Pulidoo G, D'Olivo J, Doo S, Figueiredo J, Fortunato S, Kennedy E, Lantz C, McCulloch M, González-Rivero M, Schoepf V, Smithers S, Lowe R. 2021. 'Global declines in coral reef calcium carbonate production under ocean acidification and warming'. PNAS. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2015265118

CONTACTS

Morgan Pratchett (AEST, Townsville, Australia)

P: +61 (0)488 112 295

E: morgan.pratchett@jcu.edu.au

Ryan Lowe (AWST, Perth, Australia)

P: +61 (0)466 492 719

E: Ryan.Lowe@uwa.edu.au

Scott Smithers (AEST, Townsville, Australia)

P: +61 (0)428 752 433

E: scott.smithers@jcu.edu.au

Chris Cornwall (NZST, Wellington, New Zealand)

E: christopher.cornwall@vuw.ac.nz

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION

Melissa Lyne / Coral CoE (AEST, Sydney, Australia)

P: +61 (0) 415 514 328

E: melissa.lyne@jcu.edu.au

A new study looking at the evolutionary history of the human oral microbiome shows that Neanderthals and ancient humans adapted to eating starch-rich foods as far back as 100,000 years ago, which is much earlier than previously thought.

The findings suggest such foods became important in the human diet well before the introduction of farming and even before the evolution of modern humans. And while these early humans probably didn't realize it, the benefits of bringing the foods into their diet likely helped pave the way for the expansion of the human brain because of the glucose in starch, which is the brain's main fuel source.

"We think we're seeing evidence of a really ...

ORLANDO, May 10, 2021 -University of Central Florida researchers are building on their technology that could pave the way for hypersonic flight, such as travel from New York to Los Angeles in under 30 minutes.

In their latest research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers discovered a way to stabilize the detonation needed for hypersonic propulsion by creating a special hypersonic reaction chamber for jet engines.

"There is an intensifying international effort to develop robust propulsion systems for hypersonic and supersonic flight that would allow flight through our atmosphere at very high speeds and also allow efficient entry and exit from planetary atmospheres," ...

In a newly published paper, Virginia Tech geoscientists have found that shallow wastewater injection -- not deep wastewater injections -- can drive widespread deep earthquake activity in unconventional oil and gas production fields.

Brine is a toxic wastewater byproduct of oil and gas production. Well drillers dispose of large quantities of brine by injecting it into subsurface formations, where its injection can cause earthquakes, according to Guang Zhai, a postdoctoral research scientist in the Department of Geosciences, part of the Virginia Tech College of Science, and a ...

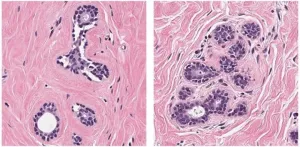

Breast cancer has recently overtaken lung cancer to become the most common cancer globally, END ...

Endometriosis, a disease found in up to 10 per cent of women, has been enigmatic since it was first described. A new theory developed by researchers at Simon Fraser University suggests a previously overlooked hormone -- testosterone -- has a critical role in its development. The research could have direct impacts on diagnosis and treatment of the disease, signaling hope for women with endometriosis worldwide.

The disease is caused by endometrial tissue growing outside of the uterus, usually in the pelvic area, where it contributes to pain, inflammation, and infertility. But why some women get it, and others do not, has remained unclear.

The new research is based on recent findings that women with endometriosis developed, as fetuses in their mother's womb, under conditions of relatively ...

Admit it: Daily commutes - those stops, the starts, all that stress - gets on your last nerve.

Or is that just me?

It might be, according to a new study from the University of Houston's Computational Physiology Lab. UH Professor Ioannis Pavlidis and his team of researchers took a look at why some drivers can stay cool behind the wheel while others keep getting more irked.

"We call the phenomenon 'accelerousal.' Arousal being a psychology term that describes stress. Accelarousal is what we identify as stress provoked by acceleration events, even small ones," said Pavlidis, ...

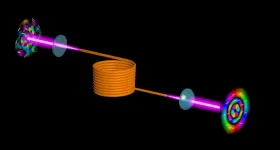

The use of multimode optical fibers to boost the information capacity of the Internet is severely hampered by distortions that occur during the transmission of images because of a phenomenon called modal crosstalk.

However, University of Rochester researchers at the Institute of Optics have devised a novel technique, described in a paper in Nature Communications, to "flip" the optical wavefront of an image for both polarizations simultaneously, so that it can be transmitted through a multimode fiber without distortion. Researchers at the University of South Florida and at the University of Southern California collaborated ...

Your local city park may be improving your health, according to a new paper led by Stanford University researchers. The research, published in END ...

After years of criticism for their lack of diversity, programs for high achievers may not be adequately serving their Black and low-income students, a new study shows.

"The potential benefits aren't equally distributed," said lead author and University of Florida College of Education professor Christopher Redding, Ph.D., who evaluated data from gifted programs in elementary schools nationwide. "The conversation up to this point has been about access, with less emphasis on how students perform once in gifted programs."

While academic achievement gains for students overall were modest -- going from ...

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. -- Log on to any app store, and parents will find hundreds of options for children that claim to be educational. But new research suggests these apps might not be as beneficial to children as they seem.

A new study analyzed some of the most downloaded educational apps for kids using a set of four criteria designed to evaluate whether an app provides a high-quality educational experience for children. The researchers found that most of the apps scored low, with free apps scoring even lower than their paid counterparts on some criteria.

Jennifer Zosh, associate professor of human development ...