(Press-News.org) Scientists have made major advances in understanding and developing treatments for many cancers by identifying genetic mutations that drive the disease. Now a team led by researchers at Weill Cornell Medicine, NewYork-Presbyterian and the New York Genome Center (NYGC) has developed a machine learning technique for detecting other modifications to DNA that have a similar effect.

The study, published May 10 in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research, focuses on a type of chemical modification to DNA, called methylation, that typically silences nearby genes. The new technique can analyze the thousands of DNA methylation changes detected in tumor cells and infer which ones are likely driving tumor growth.

Methylation is an "epigenetic" process that normally regulates gene activity across the genome by altering the structure of DNA without changing the information contained in the genes. Occasionally, though, excessive methylation, called hypermethylation, occurs near a tumor suppressor gene, silencing the gene and helping to trigger or drive the runaway cell division of cancer.

"If we can profile a large number of tumors with techniques like this, we can map the epigenetic changes that are contributing to tumor growth in certain cancers," said senior author Dr. Dan Landau, an associate professor of medicine in the Division of Hematology and Medical Oncology and a member of the Sandra and Edward Meyer Cancer Center at Weill Cornell Medicine. "Then we can use that information to improve our understanding of cancer origins, as well as to optimize treatments for individual patients."

The challenge addressed by the new technique is similar to the one cancer researchers have faced regarding DNA mutations--how to distinguish "driver" mutations from more abundant "passenger" mutations that have no effect on cancer. Though there are now sophisticated methods for making the distinction among genetic mutations, techniques for distinguishing driver methylation changes from passenger methylation changes have not been nearly as sophisticated, said Dr. Landau, who is also a core member of the NYGC and an oncologist at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center.

The new algorithm developed by Dr. Landau's team is called MethSig. It uses available information, such as the background rate of methylation in a particular area of the genome, to estimate when a given methylation change is likely to be a cancer driver.

The researchers applied the algorithm to DNA methylation maps from different tumor types and found that it inferred a small number of cancer-driver events--a median of a dozen or so, in each tumor--compared to thousands of passenger methylation changes. The patterns of inferred driver methylation were consistent across patients and tumor types, as well as other statistical features suggesting the algorithm's non-incremental increase in performance compared to existing methods.

The team further validated several of the most strongly inferred DNA methylation cancer drivers by knocking out the affected gene in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) cells, and showing that the gene's absence enhanced cell growth when the cells were untreated, and also in the presence of some standard CLL treatments. Overall, the researchers concluded that their algorithm detects likely cancer-driving methylation changes much more sensitively and selectively than current methods.

In a demonstration of the algorithm's potential for improving cancer prognosis and treatment, the researchers applied MethSig to another set of CLL samples and used its inferences to predict the aggressiveness of individual patients' cancers.

"The classifier we developed using MethSig produced estimated risks for each patient, and we found that patients with higher estimated risks were more likely to have had worse outcomes," said first author Dr. Heng Pan, a senior research associate in the HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Al?Saud Institute for Computational Biomedicine at Weill Cornell Medicine, who performed most of the experiments in the study.

The researchers plan to continue using and improving the MethSig algorithm with more cancer datasets and more comprehensive genomic information.

"Ultimately we envision being able to map the entire landscape of cancer-driving DNA methylation changes, for different tumor types and in the contexts of different treatments, so that we can expand the scope of precision medicine beyond genetics to include also the critical dimension of epigenetic changes in cancer " Dr. Landau said.

INFORMATION:

Dr. Dan Landau is a paid scientific advisory board member, speaker, and holds equity for C2i Genomics. Dr. Dan Landau is also a paid consultant for Illumina, Inc.

HOUSTON - Researchers at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center have developed a first-of-its-kind spatial atlas of early-stage lung cancer and surrounding normal lung tissue at single-cell resolution, providing a valuable resource for studying tumor development and identifying new therapeutic targets. The study was published today in Cancer Discovery, a journal of the American Association for Cancer Research.

The findings reveal a heterogeneous lung cancer ecosystem, with extensive interactions between cancer cells and the surrounding microenvironment that regulate early cancer development. ...

New research on the growth rates of coral reefs shows there is still a window of opportunity to save the world's coral reefs--but time is running out.

The international study was initiated at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies (Coral CoE), which is headquartered at James Cook University (JCU).

Co-author Professor Morgan Pratchett from Coral CoE at JCU said the results show that unless carbon dioxide emissions are drastically reduced the growth of coral reefs will be stunted.

"The threat posed by climate change to coral reefs is already very apparent based on recurrent episodes of mass coral bleaching," Prof Pratchett said. "But changing environmental conditions will have other far-reaching consequences."

Co-author Professor Ryan Lowe, from Coral CoE at The University ...

A new study looking at the evolutionary history of the human oral microbiome shows that Neanderthals and ancient humans adapted to eating starch-rich foods as far back as 100,000 years ago, which is much earlier than previously thought.

The findings suggest such foods became important in the human diet well before the introduction of farming and even before the evolution of modern humans. And while these early humans probably didn't realize it, the benefits of bringing the foods into their diet likely helped pave the way for the expansion of the human brain because of the glucose in starch, which is the brain's main fuel source.

"We think we're seeing evidence of a really ...

ORLANDO, May 10, 2021 -University of Central Florida researchers are building on their technology that could pave the way for hypersonic flight, such as travel from New York to Los Angeles in under 30 minutes.

In their latest research published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the researchers discovered a way to stabilize the detonation needed for hypersonic propulsion by creating a special hypersonic reaction chamber for jet engines.

"There is an intensifying international effort to develop robust propulsion systems for hypersonic and supersonic flight that would allow flight through our atmosphere at very high speeds and also allow efficient entry and exit from planetary atmospheres," ...

In a newly published paper, Virginia Tech geoscientists have found that shallow wastewater injection -- not deep wastewater injections -- can drive widespread deep earthquake activity in unconventional oil and gas production fields.

Brine is a toxic wastewater byproduct of oil and gas production. Well drillers dispose of large quantities of brine by injecting it into subsurface formations, where its injection can cause earthquakes, according to Guang Zhai, a postdoctoral research scientist in the Department of Geosciences, part of the Virginia Tech College of Science, and a ...

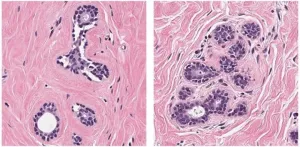

Breast cancer has recently overtaken lung cancer to become the most common cancer globally, END ...

Endometriosis, a disease found in up to 10 per cent of women, has been enigmatic since it was first described. A new theory developed by researchers at Simon Fraser University suggests a previously overlooked hormone -- testosterone -- has a critical role in its development. The research could have direct impacts on diagnosis and treatment of the disease, signaling hope for women with endometriosis worldwide.

The disease is caused by endometrial tissue growing outside of the uterus, usually in the pelvic area, where it contributes to pain, inflammation, and infertility. But why some women get it, and others do not, has remained unclear.

The new research is based on recent findings that women with endometriosis developed, as fetuses in their mother's womb, under conditions of relatively ...

Admit it: Daily commutes - those stops, the starts, all that stress - gets on your last nerve.

Or is that just me?

It might be, according to a new study from the University of Houston's Computational Physiology Lab. UH Professor Ioannis Pavlidis and his team of researchers took a look at why some drivers can stay cool behind the wheel while others keep getting more irked.

"We call the phenomenon 'accelerousal.' Arousal being a psychology term that describes stress. Accelarousal is what we identify as stress provoked by acceleration events, even small ones," said Pavlidis, ...

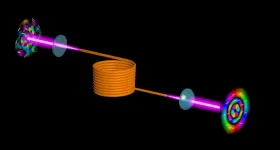

The use of multimode optical fibers to boost the information capacity of the Internet is severely hampered by distortions that occur during the transmission of images because of a phenomenon called modal crosstalk.

However, University of Rochester researchers at the Institute of Optics have devised a novel technique, described in a paper in Nature Communications, to "flip" the optical wavefront of an image for both polarizations simultaneously, so that it can be transmitted through a multimode fiber without distortion. Researchers at the University of South Florida and at the University of Southern California collaborated ...

Your local city park may be improving your health, according to a new paper led by Stanford University researchers. The research, published in END ...