INFORMATION:

This research was partially supported by the Australian Government through the Australian Research Council's Discovery Projects funding scheme.

Written by Jennifer Chu, MIT News Office

Supermassive black holes devour gas just like their petite counterparts

Regardless of size, all black holes experience similar accretion cycles, a new study finds

2021-05-17

(Press-News.org) On Sept. 9, 2018, astronomers spotted a flash from a galaxy 860 million light years away. The source was a supermassive black hole about 50 million times the mass of the sun. Normally quiet, the gravitational giant suddenly awoke to devour a passing star in a rare instance known as a tidal disruption event. As the stellar debris fell toward the black hole, it released an enormous amount of energy in the form of light.

Researchers at MIT, the European Southern Observatory, and elsewhere used multiple telescopes to keep watch on the event, labeled AT2018fyk. To their surprise, they observed that as the supermassive black hole consumed the star, it exhibited properties that were similar to that of much smaller, stellar-mass black holes.

The results, published today in the Astrophysical Journal, suggest that accretion, or the way black holes evolve as they consume material, is independent of their size.

"We've demonstrated that, if you've seen one black hole, you've seen them all, in a sense," says study author Dheeraj "DJ" Pasham, a research scientist in MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. "When you throw a ball of gas at them, they all seem to do more or less the same thing. They're the same beast in terms of their accretion."

Pasham's co-authors include principal research scientist Ronald Remillard and former graduate student Anirudh Chiti at MIT, along with researchers at the European Southern Observatory, Cambridge University, Leiden University, New York University, the University of Maryland, Curtin University, the University of Amsterdam, and the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

A stellar wake-up

When small stellar-mass black holes with a mass about 10 times our sun emit a burst of light, it's often in response to an influx of material from a companion star. This outburst of radiation sets off a specific evolution of the region around the black hole. From quiescence, a black hole transitions into a "soft" phase dominated by an accretion disk as stellar material is pulled into the black hole. As the amount of material influx drops, it transitions again to a "hard" phase where a white-hot corona takes over. The black hole eventually settles back into a steady quiescence, and this entire accretion cycle can last a few weeks to months.

Physicists have observed this characteristic accretion cycle in multiple stellar-mass black holes for several decades. But for supermassive black holes, it was thought that this process would take too long to capture entirely, as these goliaths are normally grazers, feeding slowly on gas in the central regions of a galaxy.

"This process normally happens on timescales of thousands of years in supermassive black holes," Pasham says. "Humans cannot wait that long to capture something like this."

But this entire process speeds up when a black hole experiences a sudden, huge influx of material, such as during a tidal disruption event, when a star comes close enough that a black hole can tidally rip it to shreds.

"In a tidal disruption event, everything is abrupt," Pasham says. "You have a sudden chunk of gas being thrown at you, and the black hole is suddenly woken up, and it's like, 'whoa, there's so much food -- let me just eat, eat, eat until it's gone.' So, it experiences everything in a short timespan. That allows us to probe all these different accretion stages that people have known in stellar-mass black holes."

A supermassive cycle

In September 2018, the All-Sky Automated Survey for Supernovae (ASASSN) picked up signals of a sudden flare. Scientists subsequently determined that the flare was the result of a tidal disruption event involving a supermassive black hole, which they labeled TDE AT2018fyk. Wevers, Pasham, and their colleagues jumped at the alert and were able to steer multiple telescopes, each trained to map different bands of the ultraviolet and X-ray spectrum, toward the system.

The team collected data over two years, using X-ray space telescopes XMM-Newton and the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, as well as NICER, the X-ray-monitoring instrument aboard the International Space Station, and the Swift Observatory, along with radio telescopes in Australia.

"We caught the black hole in the soft state with an accretion disk forming, and most of the emission in ultraviolet, with very few in the X-ray," Pasham says. "Then the disk collapses, the corona gets stronger, and now it's very bright in X-rays. Eventually there's not much gas to feed on, and the overall luminosity drops and goes back to undetectable levels."

The researchers estimate that the black hole tidally disrupted a star about the size of our sun. In the process, it generated an enormous accretion disk, about 12 billion kilometers wide, and emitted gas that they estimated to be about 40,000 Kelvin, or more than 70,000 degrees Fahrenheit. As the disk became weaker and less bright, a corona of compact, high-energy X-rays took over as the dominant phase around the black hole before eventually fading away.

"People have known this cycle to happen in stellar-mass black holes, which are only about 10 solar masses. Now we are seeing this in something 5 million times bigger," Pasham says.

"The most exciting prospect for the future is that such tidal disruption events provide a window into the formation of complex structures very close to the supermassive black hole such as the accretion disk and the corona," says lead author Thomas Wevers, a fellow at the European Southern Observatory. "Studying how these structures form and interact in the extreme environment following the destruction of a star, we can hopefully start to better understand the fundamental physical laws that govern their existence."

In addition to showing that black holes experience accretion in the same way, regardless of their size, the results represent only the second time that scientists have captured the formation of a corona from beginning to end.

"A corona is a very mysterious entity, and in the case of supermassive black holes, people have studied established coronas but don't know when or how they formed," Pasham says. "We've demonstrated you can use tidal disruption events to capture corona formation. I'm excited about using these events in the future to figure out what exactly is the corona."

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

Pollutants rapidly seeping into drinking water

2021-05-17

The entire ecosystem of the planet, including humans, depends on clean water. When carbonate rock weathers, karst areas are formed, from which around a quarter of the world's population obtains its drinking water. Scientists have been studying how quickly pollutants can reach groundwater supplies in karst areas and how this could affect the quality of drinking water. An international team led by Junior Professor Dr. Andreas Hartmann of the Chair of Hydrological Modeling and Water Resources at the University of Freiburg compared the time it takes water to seep down from the surface to the subsurface with the time it takes for pollutants to decompose ...

Type of heart failure may influence treatment strategies in patients with AFib

2021-05-17

Among patients with both heart failure and atrial fibrillation (AFib), treatment strategies focused on controlling the heart rhythm (using catheter ablation) and those focused on controlling the heart rate (using drugs and/or a pacemaker) showed no significant differences in terms of death from any cause or progression of heart failure, according to a study presented at the American College of Cardiology's 70th Annual Scientific Session. The trial was stopped early and, as a result, has limited statistical power to reveal differences between the two treatment approaches; however, trends observed in the study suggest the type of heart failure a patient has may influence which approach is optimal, researchers said.

Heart failure is a condition ...

Greenhouse gas and aerosol emissions are lengthening and intensifying droughts

2021-05-17

Irvine, Calif., May 17, 2021 -- Greenhouse gases and aerosol pollution emitted by human activities are responsible for increases in the frequency, intensity and duration of droughts around the world, according to researchers at the University of California, Irvine.

In a study published recently in Nature Communications, scientists in UCI's Department of Civil & Environmental Engineering showed that over the past century, the likelihood of stronger and more long-lasting dry spells grew in the Americas, the Mediterranean, western and southern Africa and eastern Asia.

"There has always been natural variability in drought events around the world, but our research shows the clear human influence on drying, specifically from anthropogenic aerosols, carbon dioxide and other ...

Family history, race and sex linked to higher rates of asthma in children

2021-05-17

DETROIT (May 17, 2021) - A national study on childhood asthma led by Henry Ford Health System has found that family history, race and sex are associated in different ways with higher rates of asthma in children.

In a study published in JAMA Pediatrics (hyperlink goes here), researchers found that children with at least one parent with a history of asthma had two to three times higher rates of asthma, mostly through age 4. They also reported that asthma rates in black children were much higher than white children during their preschool years, but the rates of incidence dropped in black children after age 9, while they increased for white children later in childhood.

"These findings help us ...

Archaeologists teach computers to sort ancient pottery

2021-05-17

Archaeologists at Northern Arizona University are hoping a new technology they helped pioneer will change the way scientists study the broken pieces left behind by ancient societies.

The team from NAU's Department of Anthropology have succeeded in teaching computers to perform a complex task many scientists who study ancient societies have long dreamt of: rapidly and consistently sorting thousands of pottery designs into multiple stylistic categories. By using a form of machine learning known as Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), the archaeologists created a computerized method that roughly emulates the thought processes of the human mind in analyzing visual information. ...

Researchers identify proteins that predict future dementia, Alzheimer's risk

2021-05-17

The development of dementia, often from Alzheimer's disease, late in life is associated with abnormal blood levels of dozens of proteins up to five years earlier, according to a new study led by researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Most of these proteins were not known to be linked to dementia before, suggesting new targets for prevention therapies.

The findings are based on new analyses of blood samples of over ten thousand middle-aged and elderly people--samples that were taken and stored during large-scale studies decades ago as part of an ongoing study. The researchers linked abnormal blood levels of 38 proteins to higher risks of developing Alzheimers within ...

Educational intervention enhances student learning

2021-05-17

May 16, 2021 -- In a study of low-income, urban youth in the U.S., researchers at Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health found that students exposed to Photovoice, an educational intervention, experienced greater improvements in STEM-capacity scores and environmental awareness scores compared to a group of youth who were not exposed to the activity. The results suggest that the Photovoice activities may be associated with improved learning outcomes. The study is published in the International Journal of Qualitative Methods.

"Our findings suggest that the Photovoice activities result in greater environmental awareness and may be associated with improved learning skills," said Nadav Sprague, doctoral fellow, ...

Stanford study reveals new biomolecule

2021-05-17

Stanford researchers have discovered a new kind of biomolecule that could play a significant role in the biology of all living things.

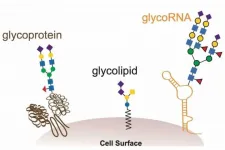

The novel biomolecule, dubbed glycoRNA, is a small ribbon of ribonucleic acid (RNA) with sugar molecules, called glycans, dangling from it. Up until now, the only kinds of similarly sugar-decorated biomolecules known to science were fats (lipids) and proteins. These glycolipids and glycoproteins appear ubiquitously in and on animal, plant and microbial cells, contributing to a wide range of processes essential for life.

The newfound glycoRNAs, neither ...

In slow motion against antibiotic resistance

2021-05-17

FRANKFURT. There are currently only a few synthetic agents that bind to and block the widespread membrane transport proteins, ATP-binding cassette transporters (ABC). Scientists at Goethe University and the University of Tokyo identified four of these macrocyclic peptides as models for a novel generation of active substances. They used methods for which the scientists involved are considered world leaders.

Thanks to deep sequencing, an extremely fast and efficient read-out procedure, the desired macrocyclic peptides could be filtered out of a "library" ...

Some RNA molecules have unexpected sugar coating

2021-05-17

In a surprise find, scientists have discovered sugar-coated RNA molecules decorating the surface of cells.

These so-called "glycoRNAs" poke out from mammalian cells' outer membrane, where they can interact with other molecules. This discovery, reported May 17, 2021, in the journal Cell, upends the current understanding of how the cell handles RNAs and glycans.

"This was probably the biggest scientific shock of my life," says study author END ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

Hairdressers could be a secret weapon in tackling climate change, new research finds

Genetic risk for mental illness is far less disorder-specific than clinicians have assumed, massive Swedish study reveals

A therapeutic target that would curb the spread of coronaviruses has been identified

Modern twist on wildfire management methods found also to have a bonus feature that protects water supplies

AI enables defect-aware prediction of metal 3D-printed part quality

Miniscule fossil discovery reveals fresh clues into the evolution of the earliest-known relative of all primates

World Water Day 2026: Applied Microbiology International to hold Gender Equality and Water webinar

The unprecedented transformation in energy: The Third Energy Revolution toward carbon neutrality

Building on the far side: AI analysis suggests sturdier foundation for future lunar bases

Far-field superresolution imaging via k-space superoscillation

10 Years, 70% shift: Wastewater upgrades quietly transform river microbiomes

Why does chronic back pain make everyday sounds feel harsher? Brain imaging study points to a treatable cause

Video messaging effectiveness depends on quality of streaming experience, research shows

Introducing the “bloom” cycle, or why plants are not stupid

The Lancet Oncology: Breast cancer remains the most common cancer among women worldwide, with annual cases expected to reach over 3.5 million by 2050

Improve education and transitional support for autistic people to prevent death by suicide, say experts

GLP-1 drugs like Ozempic could cut risk of major heart complications after heart attack, study finds

Study finds Earth may have twice as many vertebrate species as previously thought

NYU Langone orthopedic surgeons present latest clinical findings and research at AAOS 2026

New journal highlights how artificial intelligence can help solve global environmental crises

Study identifies three diverging global AI pathways shaping the future of technology and governance

Machine learning advances non targeted detection of environmental pollutants

ACP advises all adults 75 or older get a protein subunit RSV vaccine

New study finds earliest evidence of big land predators hunting plant-eaters

Newer groundwater associated with higher risk of Parkinson’s disease

New study identifies growth hormone receptor as possible target to improve lung cancer treatment

Routine helps children adjust to school, but harsh parenting may undo benefits

IEEE honors Pitt’s Fang Peng with medal in power engineering

SwRI and the NPSS Consortium release new version of NPSS® software with improved functionality

Study identifies molecular cause of taste loss after COVID

[Press-News.org] Supermassive black holes devour gas just like their petite counterpartsRegardless of size, all black holes experience similar accretion cycles, a new study finds