Study suggests tai chi can mirror healthy benefits of conventional exercise

2021-06-01

(Press-News.org) UCLA HEALTH RESEARCH BRIEF

FINDINGS

A new study shows that tai chi mirrors the beneficial effects of conventional exercise by reducing waist circumference in middle-aged and older adults with central obesity. The study was done by investigators at the University of Hong Kong, The Chinese University of Hong Kong; Chinese Academy of Sciences; and UCLA.

BACKGROUND

Central obesity is a major manifestation of metabolic syndrome, broadly defined as a cluster of cardiometabolic risk factors, including central obesity, dyslipidemia, hyperglycemia, low high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) level, and high blood pressure, that all increase risk for type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

METHOD

543 participants were randomly assigned in a 1:1:1 ratio to a control group with no exercise intervention (n= 181), conventional exercise consisting of aerobic exercise and strength training (EX group) (n= 181), and a tai chi group (TC group) (n= 181). Interventions lasted 12 weeks.

The primary outcome was waist circumference. Secondary outcomes were body weight; body mass index; high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), triglyceride, and fasting plasma glucose levels.

IMPACT

The findings suggest that tai chi is an effective approach for management of central obesity. This study has great translational significance because our findings support the notion of incorporating tai chi into global physical activity guidelines for middle-aged and older adults with central obesity.

INFORMATION:

AUTHORS

Parco M. Siu, PhD; Angus P. Yu, MPhil; Edwin C. Chin, BScEd; Doris S. Yu, PhD; Daniel Y. Fong, PhD (University of Hong Kong); Stanley S. Hui, EdD; Jean Woo, MD (The Chinese University of Hong Kong,); Gao X. Wei, PhD (Chinese Academy of Sciences); and Michael R. Irwin, MD (University of California, Los Angeles).

JOURNAL

Annals of Internal Medicine

Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/M20-7014

FUNDING

The Health and Medical Research Fund (12131841) of the Food and Health Bureau, Hong Kong SAR.

ELSE PRESS RELEASES FROM THIS DATE:

2021-05-31

A new study published in Proceedings of National Academics of Sciences finds that individuals who falsely believe they are able to identify false news are more likely to fall victim to it. In the article published today, Ben Lyons, assistant professor of communication at the University of Utah, and his colleagues examine the concern about the public's susceptibility to false news due to their inability to recognize their own limitations in identifying such information.

"Though Americans believe confusion caused by false news is extensive, relatively few indicate having seen or shared it," said Lyons. "If people incorrectly see themselves as highly skilled at identifying false news, they may unwittingly be more likely to consume, believe and share it, especially if it conforms to their ...

2021-05-31

Phosphate pollution in rivers, lakes and other waterways has reached dangerous levels, causing algae blooms that starve fish and aquatic plants of oxygen. Meanwhile, farmers worldwide are coming to terms with a dwindling reserve of phosphate fertilizers that feed half the world's food supply.

Inspired by Chicago's many nearby bodies of water, a Northwestern University-led team has developed a way to repeatedly remove and reuse phosphate from polluted waters. The researchers liken the development to a "Swiss Army knife" for pollution remediation as they tailor their membrane to absorb ...

2021-05-31

Very high atmospheric CO2 levels can explain the high temperatures on the still young Earth three to four billion years ago. At the time, our Sun shone with only 70 to 80 per cent of its present intensity. Nevertheless, the climate on the young Earth was apparently quite warm because there was hardly any glacial ice. This phenomenon is known as the 'paradox of the young weak Sun.' Without an effective greenhouse gas, the young Earth would have frozen into a lump of ice. Whether CO2, methane, or an entirely different greenhouse gas heated up planet Earth is a matter of debate among scientists. New research by Dr ...

2021-05-31

Art Garfunkel once described his legendary musical chemistry with Paul Simon, "We meet somewhere in the air through the vocal cords ... ." But a new study of duetting songbirds from Ecuador, the plain-tail wren (Pheugopedius euophrys), has offered another tune explaining the mysterious connection between successful performing duos.

It's a link of their minds, and it happens, in fact, as each singer mutes the brain of the other as they coordinate their duets.

In a study published May 31 in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, a team of researchers studying brain ...

2021-05-31

Three groups (Dr. James Birchler's group from University of Missouri, Dr. Jan Barto's group from Institute of Experimental Botany of the Czech Academy of Sciences and Dr. HAN Fangpu's group from the Institute of Genetics and Developmental Biology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences) recently reported a reference sequence for the supernumerary B chromosome in maize in a study published online in PNAS (doi:10.1073/pnas.2104254118).

Supernumerary B chromosomes persist in thousands of plant and animal genomes despite being nonessential. They are maintained in populations by mechanisms of "drive" that make them inherited at higher than typical Mendelian rates. Key properties such as its origin, evolution, and the molecular mechanism for its accumulation in ...

2021-05-31

While it is widely accepted that climate change drove the evolution of our species in Africa, the exact character of that climate change and its impacts are not well understood. Glacial-interglacial cycles strongly impact patterns of climate change in many parts of the world, and were also assumed to regulate environmental changes in Africa during the critical period of human evolution over the last ~1 million years. The ecosystem changes driven by these glacial cycles are thought to have stimulated the evolution and dispersal of early humans.

A paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) this week challenges this view. Dr. Kaboth-Bahr ...

2021-05-31

The Sahara has not always been covered by only sand and rocks. During the period from 14,500 to 5,000 years ago large areas of North Africa were more heavily populated, and where there is desert today the land was green with vegetation. This is evidenced by various sites with rock paintings showing not only giraffes and crocodiles, but even illustrating people swimming in the "Cave of Swimmers". This period is known as the Green Sahara or African Humid Period. Until now, researchers have assumed that the necessary rain was brought from the tropics through an enhanced summer monsoon. The northward shift of the monsoon was attributed to rotation of the Earth's tilted axis that produces higher levels of ...

2021-05-31

An emotion regulation strategy known as cognitive reappraisal helped reduce the typically heightened and habitual attention to drug-related cues and contexts in cocaine-addicted individuals, a study by Mount Sinai researchers has found. In a paper published in PNAS, the team suggested that this form of habit disruption, mediated by the prefrontal cortex (PFC) of the brain, could play an important role in reducing the compulsive drug-seeking behavior and relapse that are the hallmarks, and long-standing challenges, of addiction.

"Relapse in addiction is often precipitated by heightened attention-bias to drug-related cues, which could consist of sights, smells, ...

2021-05-31

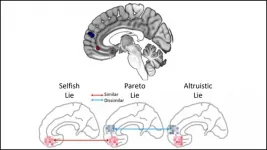

You may think a little white lie about a bad haircut is strictly for your friend's benefit, but your brain activity says otherwise. Distinct activity patterns in the prefrontal cortex reveal when a white lie has selfish motives, according to new research published in JNeurosci.

White lies -- formally called Pareto lies -- can benefit both parties, but their true motives are encoded by the medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC). This brain region computes the value of different social behaviors, with some subregions focusing on internal motivations and others on external ones. Kim and Kim predicted activity patterns in these subregions could elucidate the true motive behind white lies.

The research team deployed a stand in for white lies, having participants tell lies to earn a reward ...

2021-05-31

By including multi-ethnic participants, a largescale genetic study has identified more regions of the genome linked to type 2 diabetes-related traits than if the research had been conducted in Europeans alone.

The international MAGIC collaboration, made up of more than 400 global academics, conducted a genome-wide association meta-analysis led by the University of Exeter. Now published in Nature Genetics, their findings demonstrate that expanding research into different ancestries yields more and better results, as well as ultimately benefitting global patient care.

Up to now, nearly 87 per cent of ...

LAST 30 PRESS RELEASES:

[Press-News.org] Study suggests tai chi can mirror healthy benefits of conventional exercise