(Press-News.org) At Boston University, a team of researchers is working to better understand how language and speech is processed in the brain, and how to best rehabilitate people who have lost their ability to communicate due to brain damage caused by a stroke, trauma, or another type of brain injury. This type of language loss is called aphasia, a long-term neurological disorder caused by damage to the part of the brain responsible for language production and processing that impacts over a million people in the US.

"It's a huge problem," says Swathi Kiran, director of BU's Aphasia Research Lab, and College of Health & Rehabilitation Sciences: Sargent College associate dean for research and James and Cecilia Tse Ying Professor in Neurorehabilitation. "It's something our lab is working to tackle at multiple levels."

For the last decade, Kiran and her team have studied the brain to see how it changes as people's language skills improve with speech therapy. More recently, they've developed new methods to predict a person's ability to improve even before they start therapy. In a new paper published in Scientific Reports, Kiran and collaborators at BU and the University of Texas at Austin report they can predict language recovery in Hispanic patients who speak both English and Spanish fluently--a group of aphasia patients particularly at risk of long-term language loss--using sophisticated computer models of the brain. They say the breakthrough could be a game changer for the field of speech therapy and for stroke survivors impacted by aphasia.

"This [paper] uses computational modeling to predict rehabilitation outcomes in a population of neurological disorders that are really underserved," Kiran says. In the US, Hispanic stroke survivors are nearly two times less likely to be insured than all other racial or ethnic groups, Kiran says, and therefore they experience greater difficulties in accessing language rehabilitation. On top of that, oftentimes speech therapy is only available in one language, even though patients may speak multiple languages at home, making it difficult for clinicians to prioritize which language a patient should receive therapy in.

"This work started with the question, 'If someone had a stroke in this country and [the patient] speaks two languages, which language should they receive therapy in?'" says Kiran. "Are they more likely to improve if they receive therapy in English? Or in Spanish?"

This first-of-its-kind technology addresses that need by using sophisticated neural network models that simulate the brain of a bilingual person that is language impaired, and their brain's response to therapy in English and Spanish. The model can then identify the optimal language to target during treatment, and predict the outcome after therapy to forecast how well a person will recover their language skills. They found that the models predicted treatment effects accurately in the treated language, meaning these computational tools could guide healthcare providers to prescribe the best possible rehabilitation plan.

"There is more recognition with the pandemic that people from different populations--whether [those be differences of] race, ethnicity, different disability, socioeconomic status--don't receive the same level of [healthcare]," says Kiran. "The problem we're trying to solve here is, for our patients, health disparities at their worst; they are from a population that, the data shows, does not have great access to care, and they have communication problems [due to aphasia]."

As part of this work, the team is examining how recovery in one language impacts recovery of the other--will learning the word "dog" in English lead to a patient recalling the word "perro," the word for dog in Spanish?

"If you're bilingual you may go back and forth between languages, and what we're trying to do [in our lab] is use that as a therapy piece," says Kiran.

Clinical trials using this technology are already underway, which will soon provide an even clearer picture of how the models can potentially be implemented in hospital and clinical settings.

"We are trying to develop effective therapy programs, but we also try to deal with the patient as a whole," Kiran says. "This is why we care deeply about these health disparities and the patient's overall well-being."

INFORMATION:

The new drug sotorasib reduces tumor size and shows promise in improving survival among patients with lung tumors caused by a specific DNA mutation, according to results of a global phase 2 clinical trial. The drug is designed to shut down the effects of the mutation, which is found in about 13% of patients with lung adenocarcinoma, a common type of non-small-cell lung cancer.

The Food and Drug Administration approved sotorasib May 28 as a targeted therapy for patients with non-small-cell lung cancer whose tumors express a specific mutation -- called ...

PROVIDENCE, R.I. [Brown University] -- A new study of monsoon rainfall on the Indian subcontinent over the past million years provides vital clues about how the monsoons will respond to future climate change.

The study, published in Science Advances, found that periodic changes in the intensity of monsoon rainfall over the past 900,000 years were associated with fluctuations in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2), continental ice volume and moisture import from the southern hemisphere Indian Ocean. The findings bolster climate model predictions that rising CO2 and higher global temperatures will lead to stronger monsoon seasons.

"We show that over the last 900,000 years, higher CO2 levels along with associated changes in ice volume and moisture ...

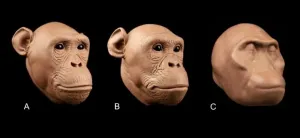

Accurate soft tissue measurements are critical when making reconstructions of human ancestors, a new study from the University of Adelaide and Arizona State University has found.

"Reconstructing extinct members of the Hominidae, or hominids, including their facial soft tissue, has become increasingly popular with many approximations of their faces presented in museum exhibitions, popular science publications and at conference presentations worldwide," said lead author PhD student Ryan M. Campbell from the University of Adelaide.

"It is essential that accurate facial soft tissue thickness measurements are used when reconstructing the faces of hominids to reduce the variability exhibited in reconstructions of the same individuals."

Hominids have been readily accepted ...

A new study shows that substantial amounts of carbon dioxide were released during the last millennium because of crop cultivation on peatlands in the Northern Hemisphere.

Only about half of the carbon released through the conversion of peat to croplands was compensated by continuous carbon absorption in natural northern peatlands.

Peatlands are a type of wetland which store more organic carbon than any other type of land ecosystem in the world.

Due to waterlogged conditions, dead plant materials do not fully decay and carbon accumulates in peatlands over thousands of years.

Therefore, natural peatlands help to cool the climate by capturing carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere ...

ABSTRACT #9003

HOUSTON - Results from the Phase II cohort of the CodeBreaK 100 study showed that treatment with the KRAS G12C inhibitor sotorasib achieved a 37.1% objective response rate and 12.5 months median overall survival in previously treated patients with KRAS G12C-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), according to researchers from The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center. The findings were presented today at the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) Annual Meeting and published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

Trial results indicated the targeted therapy was safe and tolerable in a heavily pre-treated patient population. The reported findings make sotorasib the first KRAS G12C inhibitor to demonstrate overall survival benefit in a registrational ...

A research group of the Department of Pharmacy and Biotechnology of the University of Bologna analyzed more than one million SARS-CoV-2 genome sequences. This analysis led to the identification of a new variant that, over the past weeks, has been spreading mostly in Mexico but has also been found in Europe. Their paper published in the Journal of Medical Virology presented the so-called "Mexican variant", whose scientific name is T478K. Like other strains, this presents a mutation in the Spike protein, which allows coronaviruses to attach to and penetrate their targeted cells.

"This variant has been increasingly spreading among people in North America, particularly in Mexico. To date, this variant covers more than 50% of the existing viruses in this area. The ...

Tiny algae in Earth's oceans and lakes take in sunlight and carbon dioxide and turn them into sugars that sustain the rest of the aquatic food web, gobbling up about as much carbon as all the world's trees and plants combined.

New research shows a crucial piece has been missing from the conventional explanation for what happens between this first "fixing" of CO2 into phytoplankton and its eventual release to the atmosphere or descent to depths where it no longer contributes to global warming. The missing piece? Fungus.

"Basically, carbon moves up the food chain in aquatic environments differently than we commonly think it does," said Anne Dekas, an assistant professor of Earth system science at Stanford University. Dekas is the senior ...

Though it might seem inanimate, the soil under our feet is very much alive. It's filled with countless microorganisms actively breaking down organic matter, like fallen leaves and plants, and performing a host of other functions that maintain the natural balance of carbon and nutrients stored in the ground beneath us.

"Soil is mostly microorganisms, both alive and dead," says END ...

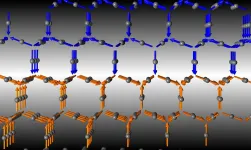

Like all metals, silver, copper, and gold are conductors. Electrons flow across them, carrying heat and electricity. While gold is a good conductor under any conditions, some materials have the property of behaving like metal conductors only if temperatures are high enough; at low temperatures, they act like insulators and do not do a good job of carrying electricity. In other words, these unusual materials go from acting like a chunk of gold to acting like a piece of wood as temperatures are lowered. Physicists have developed theories to explain this so-called metal-insulator transition, but the mechanisms behind the transitions are not ...

There's a lot of interest right now in how different microbiomes--like the one made up of all the bacteria in our guts--could be harnessed to boost human health and cure disease. But Daniel Segrè has set his sights on a much more ambitious vision for how the microbiome could be manipulated for good: "To help sustain our planet, not just our own health."

Segrè, director of the END ...